Subtle Treatise on Landscapes

By Santiago Villanueva

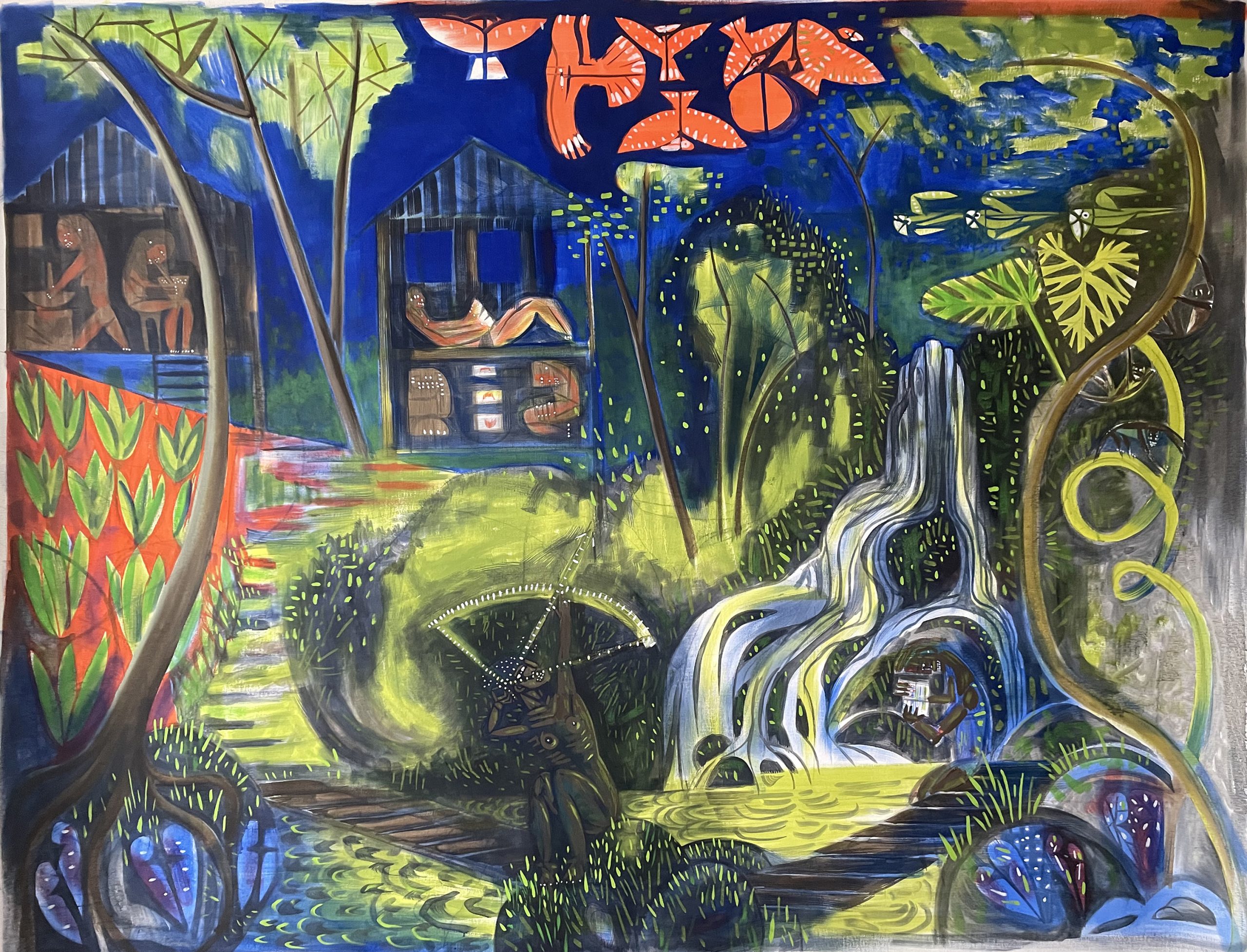

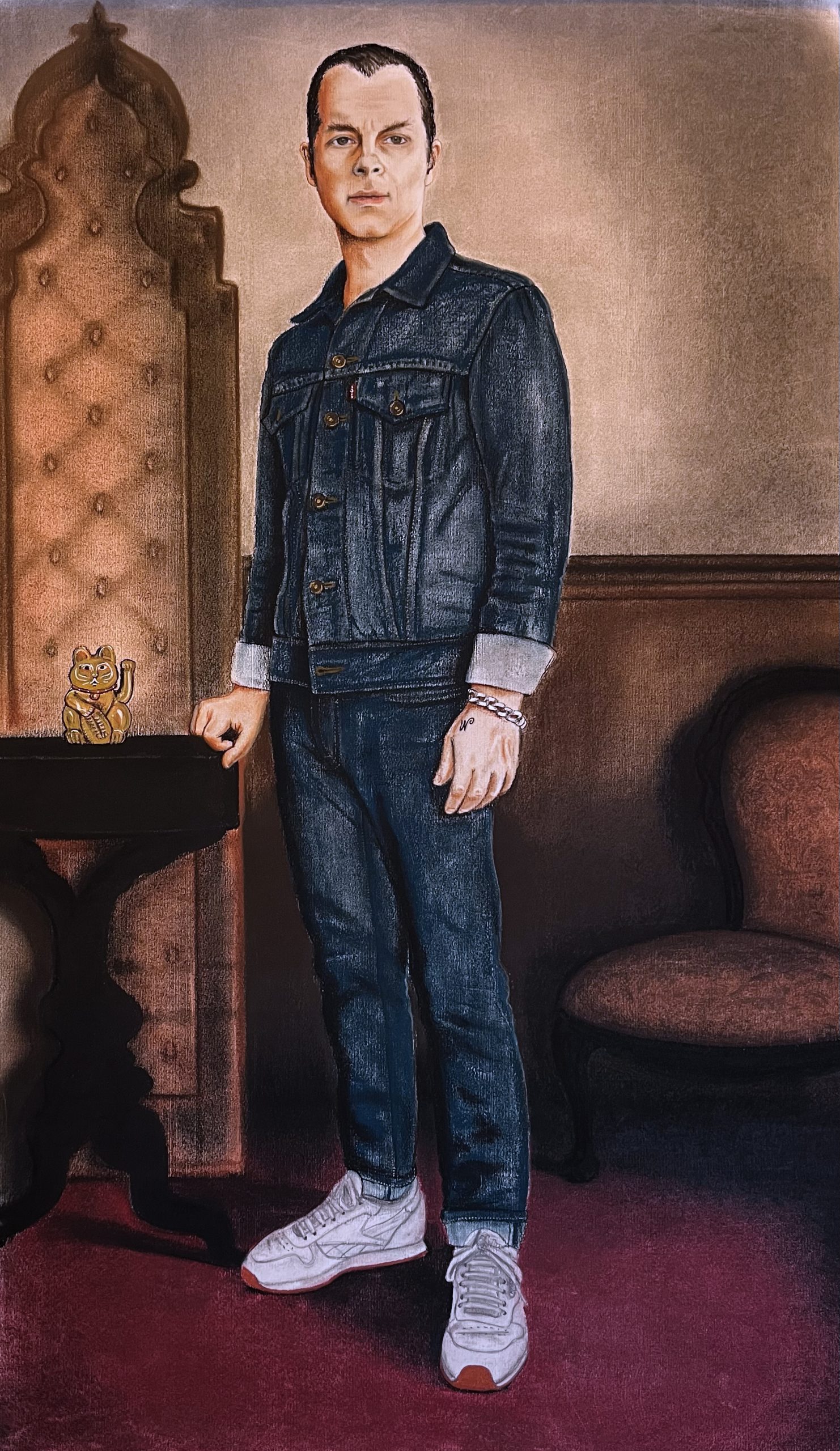

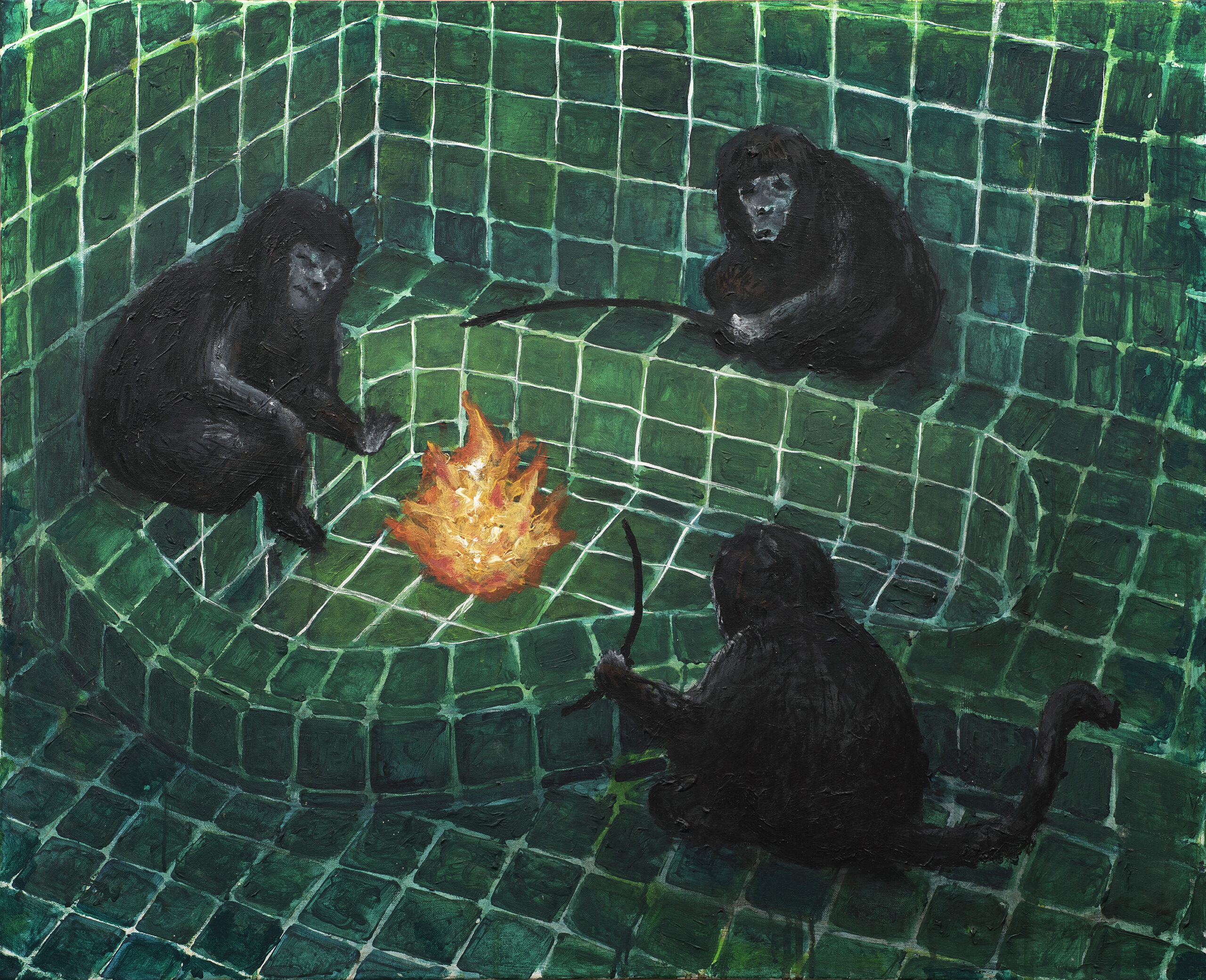

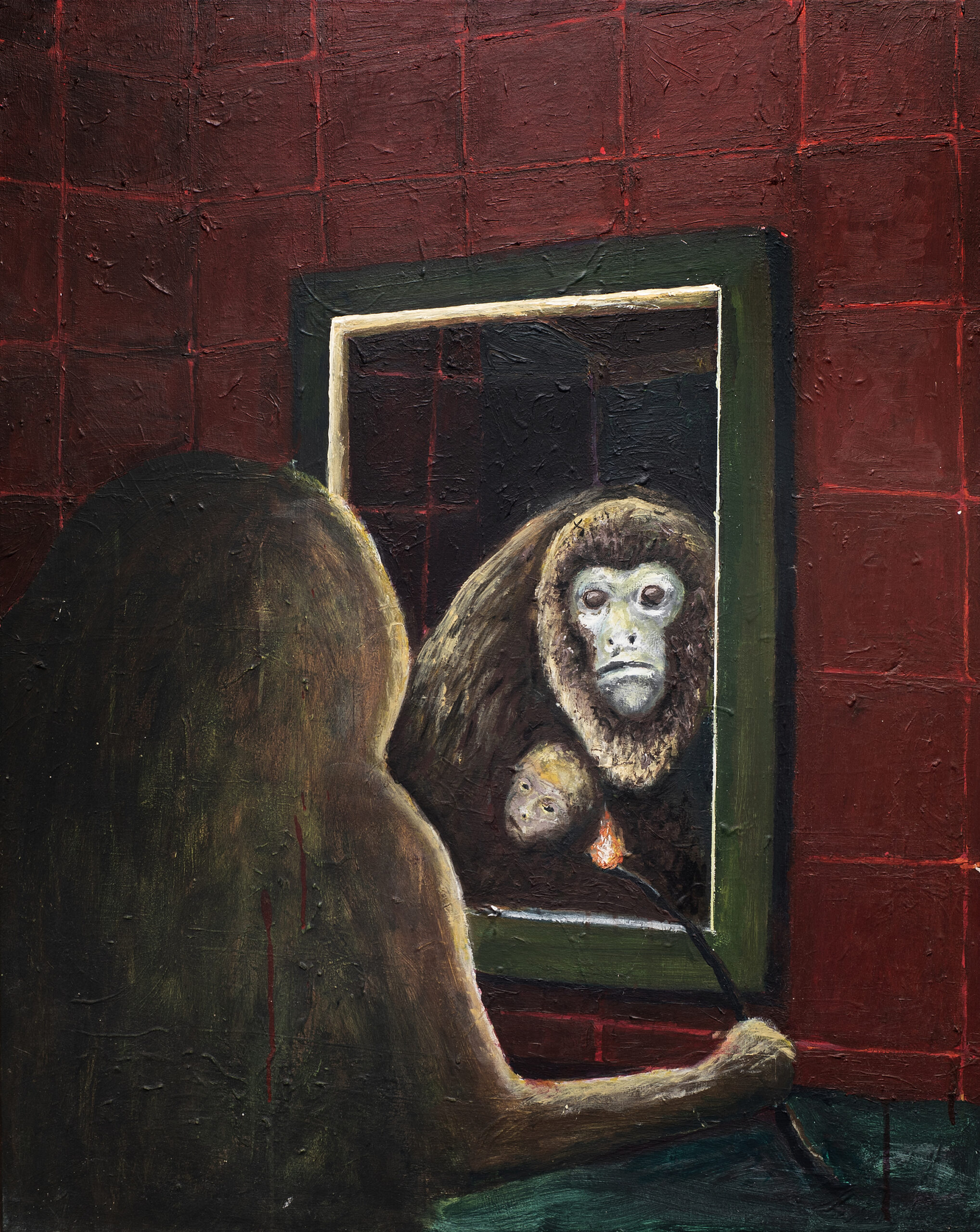

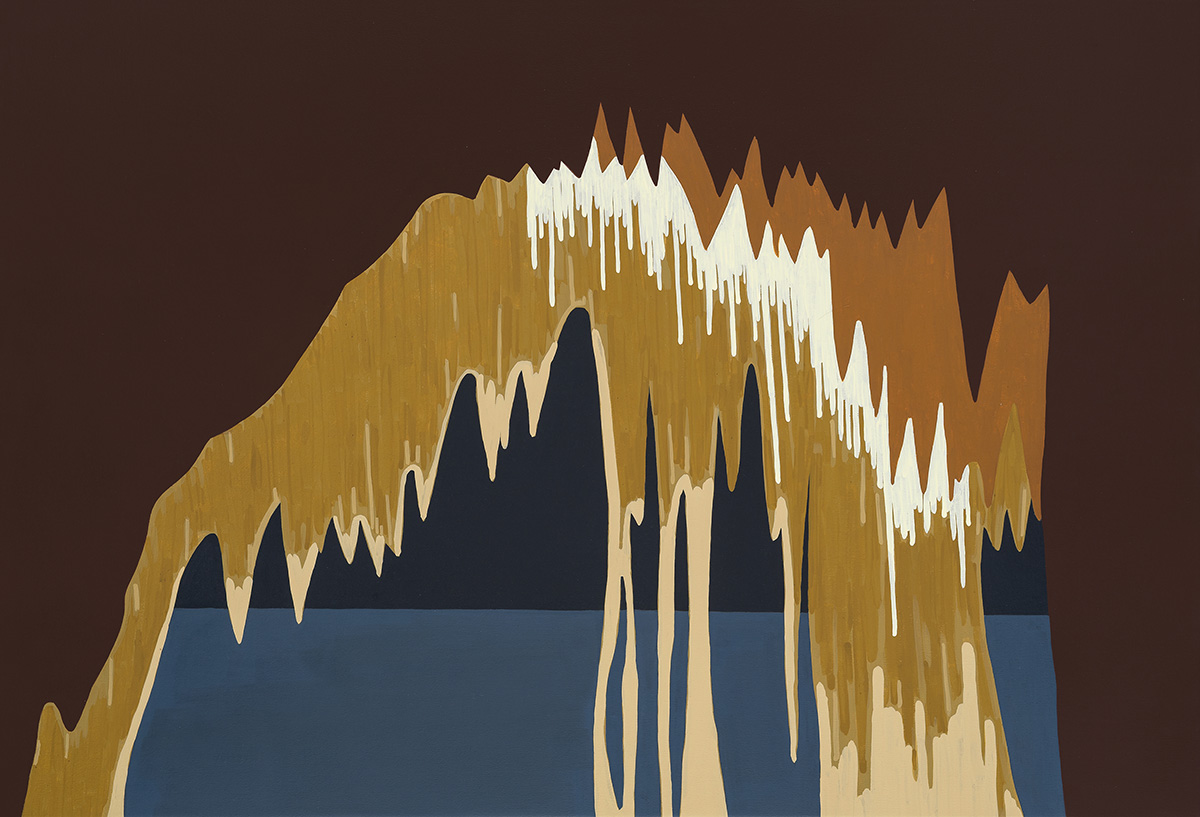

Florencia Böhtlingk (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1966) has worked on the landscape theme

since the early nineteen-nineties. The location of her first landscapes was not specific, but

hazy, indefinite. They tended to a damp surrealism like the surrealism of the Grupo Litoral1, a

surrealism characterized by vegetation, the earth, and a dubious atmosphere, a surrealism akin

to Argentine painter Marcia Schwartz’s work from the nineteen-eighties as well as to what I

like to call “pink surrealism” which is nowhere on the agenda and recalcitrant to any consensus,

a surrealism where the image is a bit rarefied. Starting in the late nineties, her painting began

to settle. At stake, from that point on, is neither a generic landscape nor a broad geography, but

rather a specific and determined landscape, a minimal and proximate space: an autobiography.

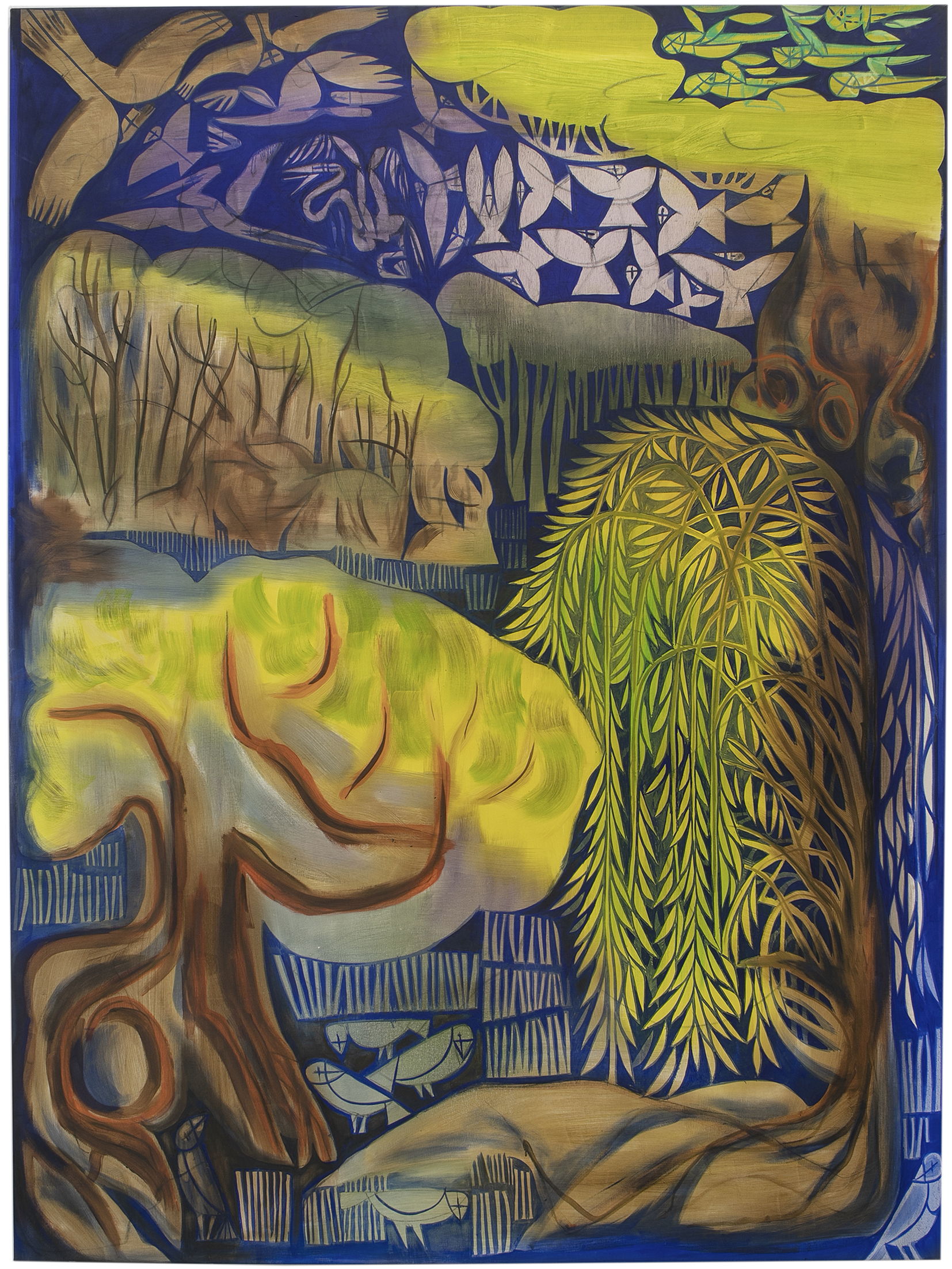

To say Misiones ( province in the Argentine littoral that borders on Brazil, Paraguay, and

Uruguay) or to say Río de la Plata in Florencia Böhtlingk’s painting does not mean to refer to a

prototypical landscape, but rather to a happenstance. How to bind the landscape of Misiones to

Florencia’s painting? As an encounter that, over time, has gone beyond experience. It contains

an instance of obsession—just like observing the life of birds, where the only way to come to

know things is by spending time and describing. Knowing as a means not to capture, but to

grasp to be able to better relate, to be able to name and tend. Painting, the act of painting,

is a passive attitude before the landscape: Learning so that others can learn. Florencia and I

spoke of Vinciane Despret and her book “Living as a Bird” because it elaborates on the ideas—

there are so many—of what a territory can be when edges are much blurrier than any notion

of border or limit. The song of birds, the smell of many mammals delimits, and painting can,

perhaps, be read as many registers of a territory. It might have as much to do with wooing

others as with the visualization of the small or the overly animated.

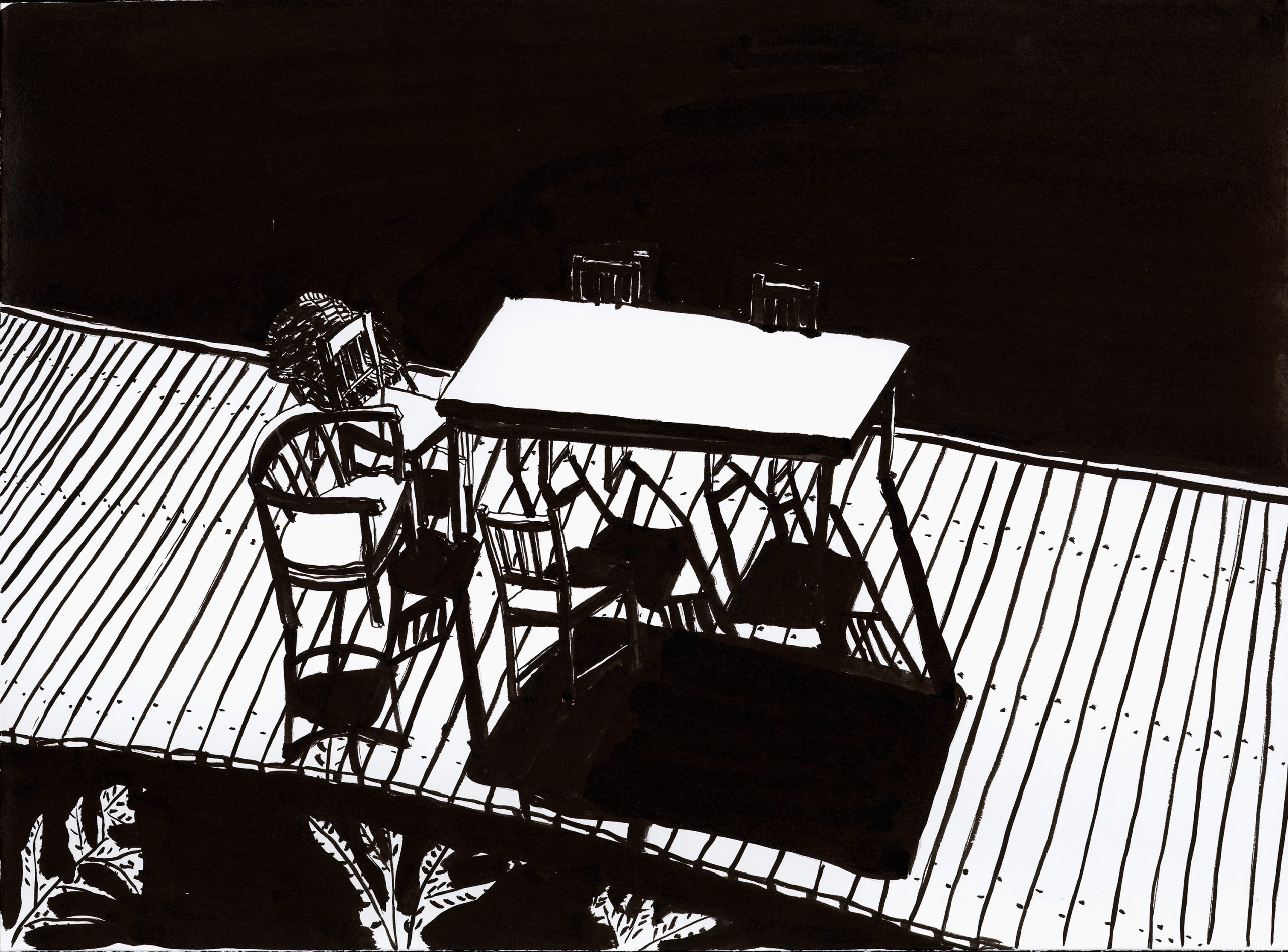

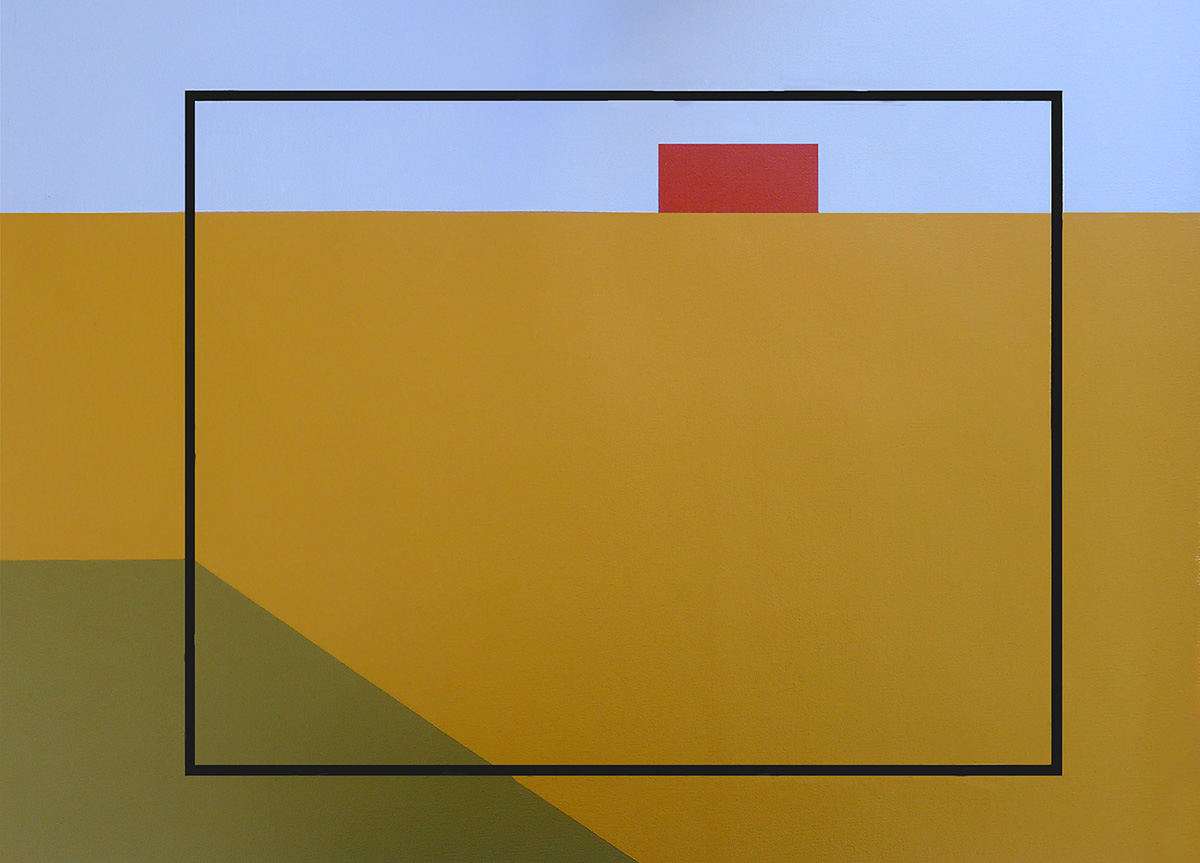

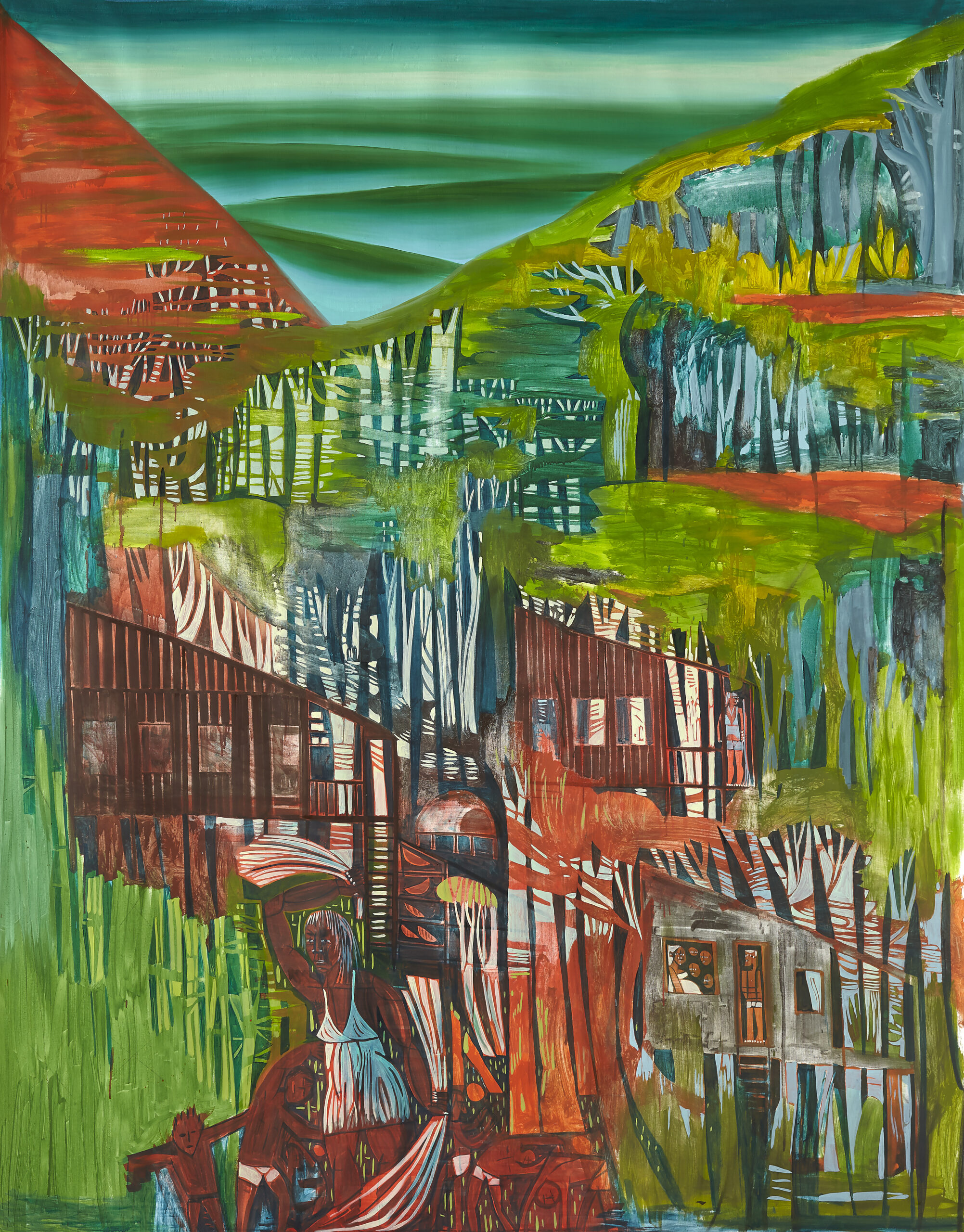

Florencia does not paint the Misiones landscape; she approaches a small landscape located in

Misiones: the Colonia La Flor, La Bonita inn, which are part of her life story. That is what sets

her apart from the twentieth century. To paint a landscape is to paint anecdotes, days lived—

it is a diary of sorts. There is, here, no rootedness, no localism, no foundational—let alone

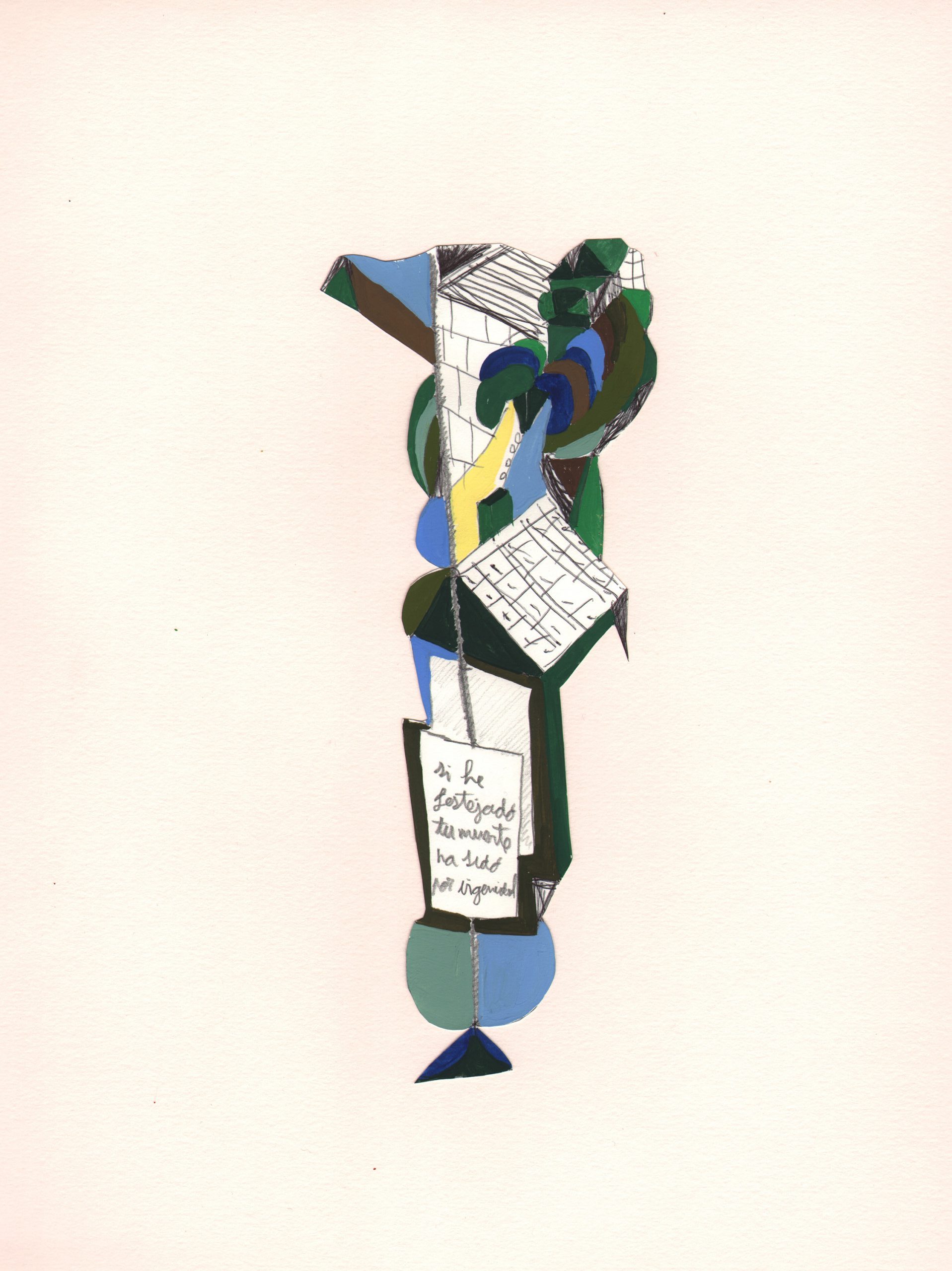

national—history. Misiones is a limit. A geographic and political borderline where the language

is mix, the vegetation is mix. The line that divides one thing from another is, in Misiones, fragile.

There is no defense of or pride in the concrete, but in the mix. The birds, like the foods, have

more than one name, and the ways those names are uttered are no less variable—we are, in

Misiones, somewhere between collage and unfinishedness . Technique paves the way for that

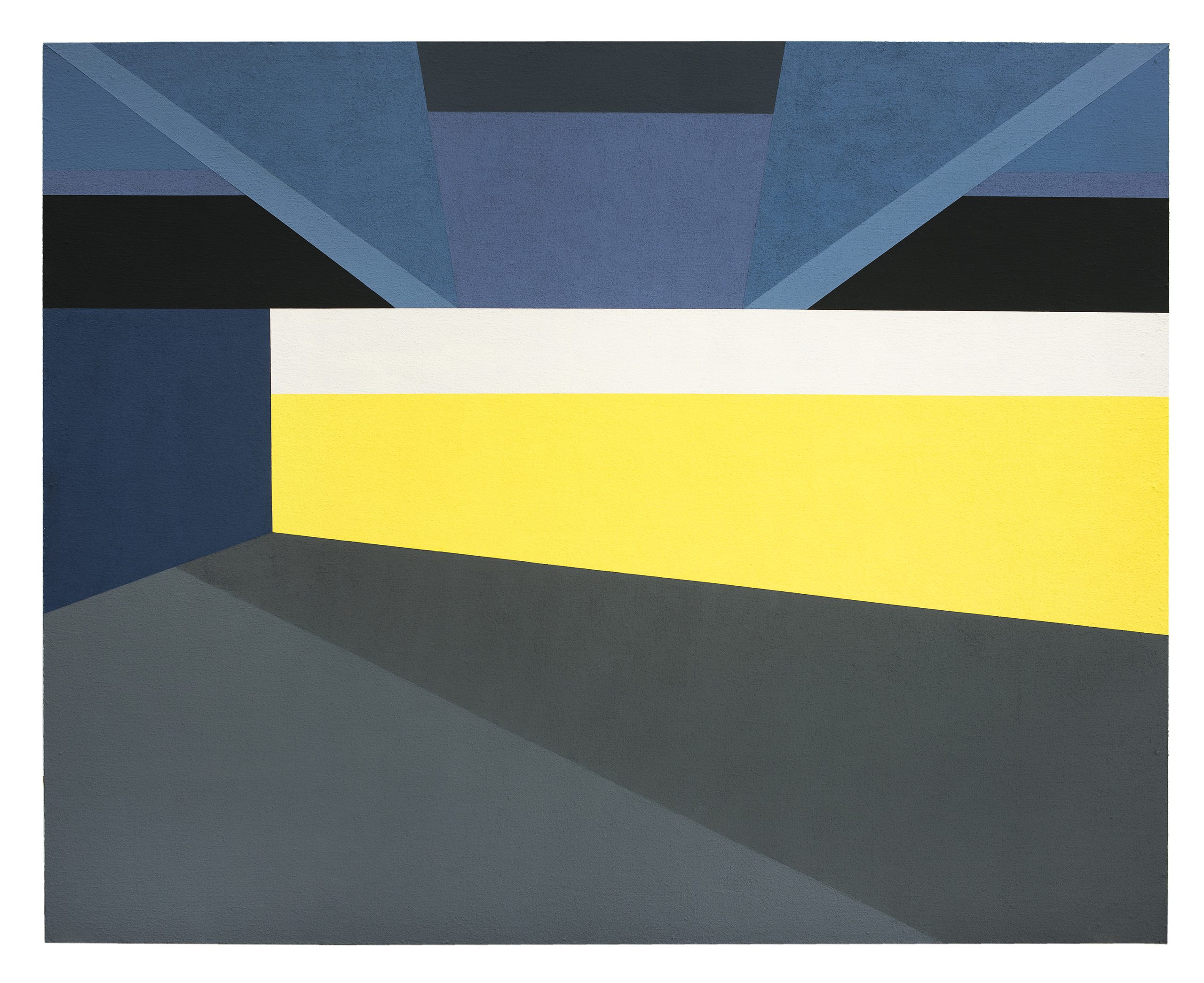

experience. Each of Florencia’s paintings rests on previous decisions that define often-parallel

paths between images: from an imprecise gouache to a rigid color plane; from the speed of

works on paper to the detail and exactingness of works on canvas. Proper names repeat;

rather than journey, there is installment; rather than the impulse to visit, there is the impulse

to engage. But there are also stories that lead to other stories—a network. The landscape as a

space to hold stories (landscape as bag). It holds the Jesuits, the back-and-forth over borders,

domestic migration, the mix of languages, words, tourism, the writer Horacio Quiroga, and the

painter Carlos Giambiagi.2

Florencia’s painting now has a place in Buenos Aires, a city inclined to painting, a city where

contemporary art is not swayed by the tides of agendas or where those agendas are genuinely

infiltrated. Looking at her paintings is a good way to look back at the twentieth century in the

South, but also to keep asking that question about resistance to theme. To refuse theme is,

in a sense, to give less over, to categorize less, but as resistance. It means not representing

what is expected, what is described in everyday speak as “being in the throes of something,” a

drunken episode that is also a fit of madness, but that, as with many forms of activism, is only

recognized as such from the distance.

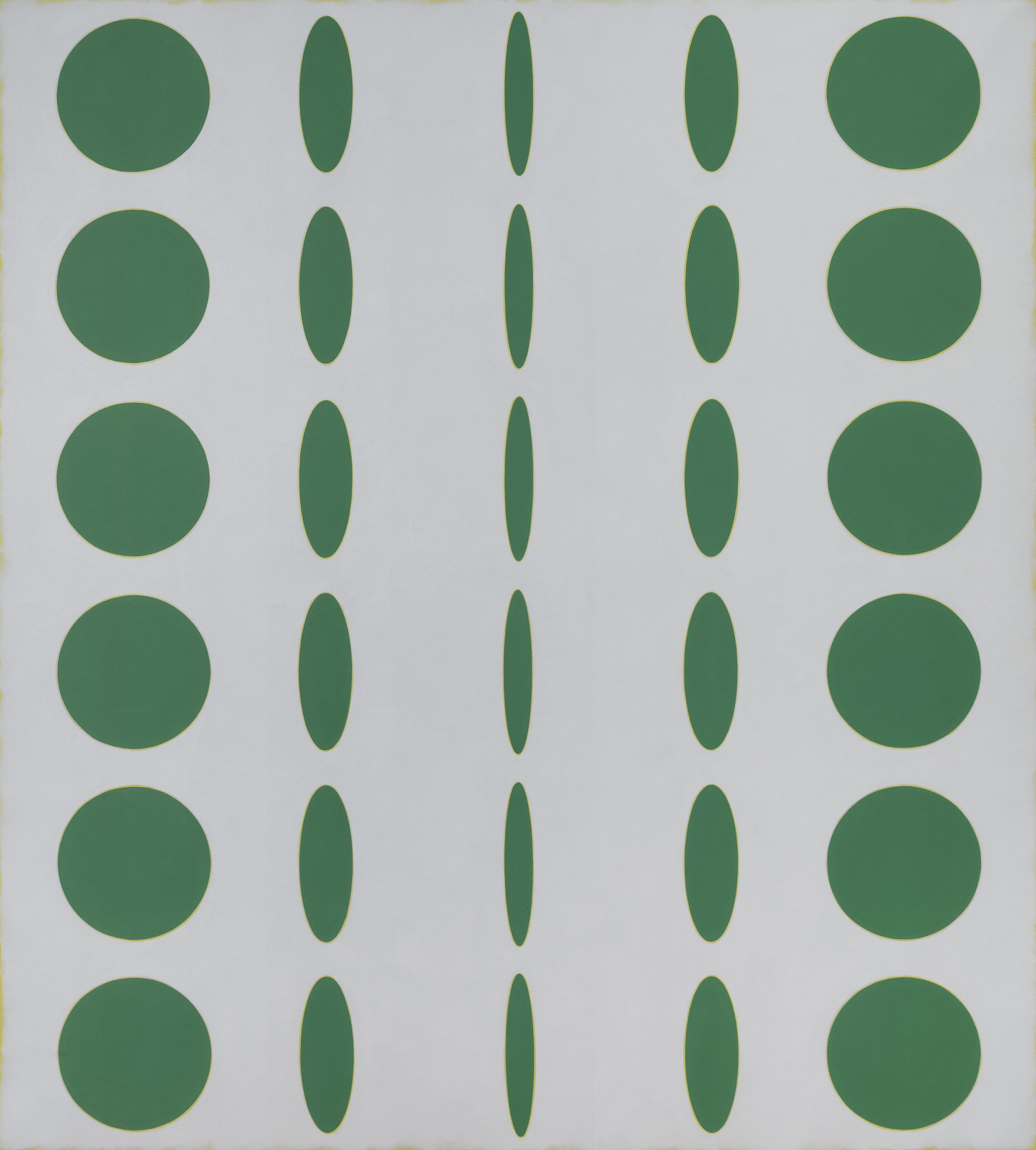

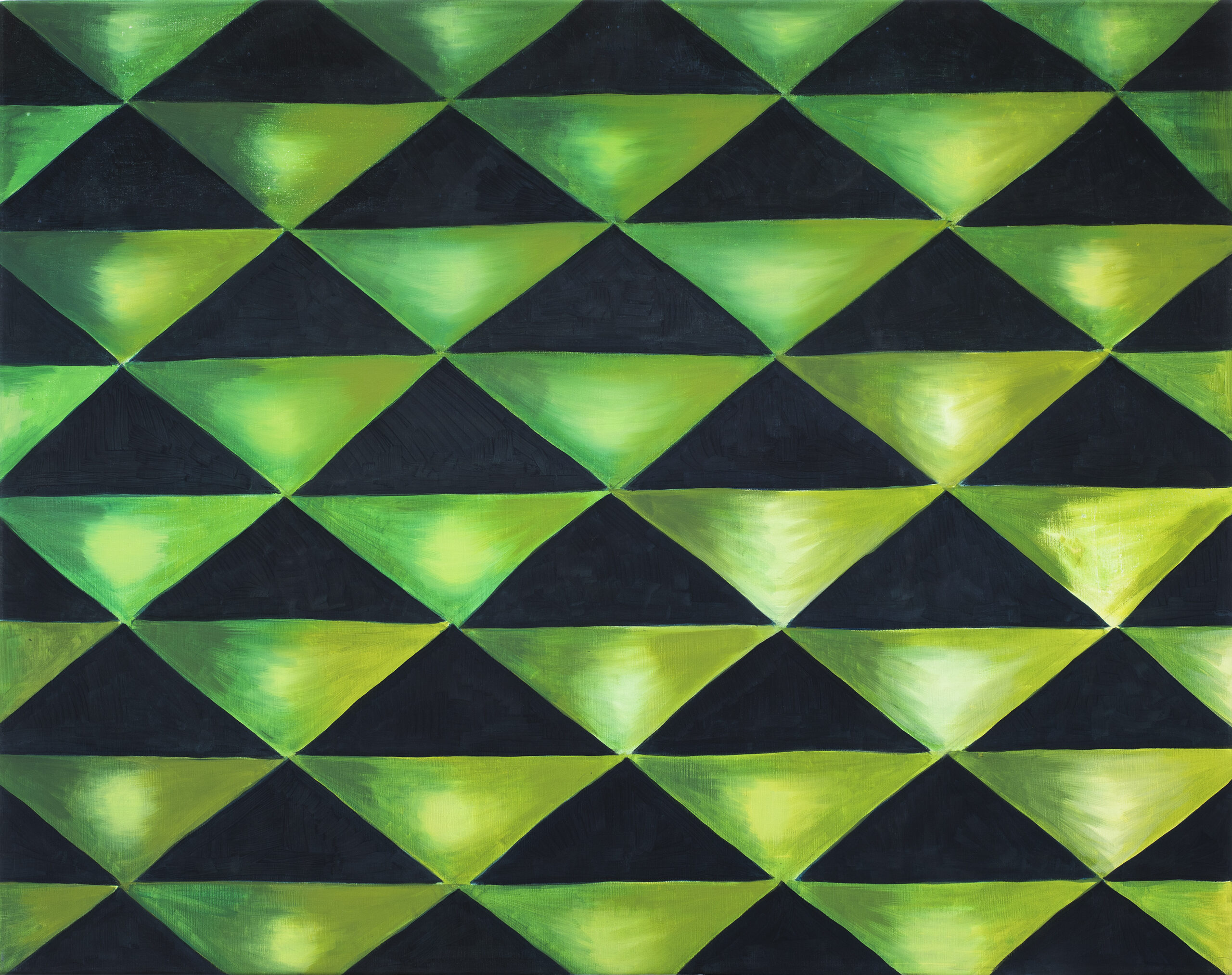

Landscape in the early-twentieth-century tradition of the South is marked by reading, for the

sake of technique, André Lothe’s book “Treatise on Landscape Painting.” Art history ensured

that that was required reading for several generations. Still, some marginal local writings that

strayed from that path make for interesting reading today—among them works by Rodrigo

Bonome and Carlos Quiroga, even though their tone is caught up in their times. One speaks

of geometry as search for balance, and the other of the relationship between landscape and

love. Rodrigo Bonome says, “Geometry is to landscape as cage is to bird—that is, a resource

that confers balance. Under the rigor of geometric laws, landscape is freed of any line that

does not play a categorical role. In submission to geometry lies an intention, a purpose—

and that is synthesis. And to say synthesis is to say essence, is to say purging.” At play in

landscape, at least as point of departure, is that fenced-in-ness or frustration of which Bonome

speaks, and Florencia invents a thousand possible ways for painting to escape representation

and embrace telling stories. Pursuant to convoluted readings of Martín Fierro, Carlos Quiroga

relates landscape to love. “Love tends to unification. When the lover’s spirit has penetrated

a piece of land, spiritualizing and beautifying it such that, in aesthetic terms, the spirit is the

landscape rendered soul and the landscape the soul objectified, then, and only then, can the

befitting spiritual creations be manifested.” Though those phrases can only be read from the

vision of a Europeanized twentieth century, I think there are certain avant-garde deviations,

insofar as that means moving within what is supposedly known. Landscape as form of escape

and also as unity, but envisioned not as something that equalizes but rather as something that

allows for proximity. That is why what enables Florencia to paint the landscape is not only

permanence and observation , but also conversations, narratives, small stories. Her paintings,

regardless of size, are always small stories. Hence, each one needs differences and specific

decisions, whether regarding color, brushstroke, or format.

In recent decades, Florencia has painted out in nature, searching for ways to connect. And that

is evident in a selection of works that, despite gaps, is encompassing of her production over

the course of years. It ranges from less flat brushstrokes to more accentuated planes, from

specific snippets of landscape to broader scenes, from the precise to the imprecise and back

again—something specific to vision and doubt, but also a subtle treatise toward affinities.3

1 The Grupo Litoral brought together artists, among them Juan Grela (1914–1992), who lived in the Argentinethe province of Santa Fé. The themes of their work were tied to the Paraná River that runs through that province and reaches as far north as Paraguay. The Grupo Litoral is, today, of interest to many contemporary artists.

2 Writer Horacio Quiroga (Salto, Uruguay 1878–Buenos Aires, 1937) lived in Misiones province, where he wrote a great many stories. He and his friend, anarchist artist Carlos Giambiagi (Salto, Uruguay 1887–Buenos Aires, 1965), collaborated on many book projects.

3 I would like to posit a relationship between Florencia’s painting and Vivian Suter’s. Suter is an Argentine painter who has lived in Guatemala since 1982. In recent decades, she—like Florencia—has painted nature as a way to connect.