EL CUERPO ES AVANT GARDE

SOFÍA QUIRNO

CURADURÍA LAURA HAKEL

MAR 23. 2023 — JUN 30. 2023

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

WORKS

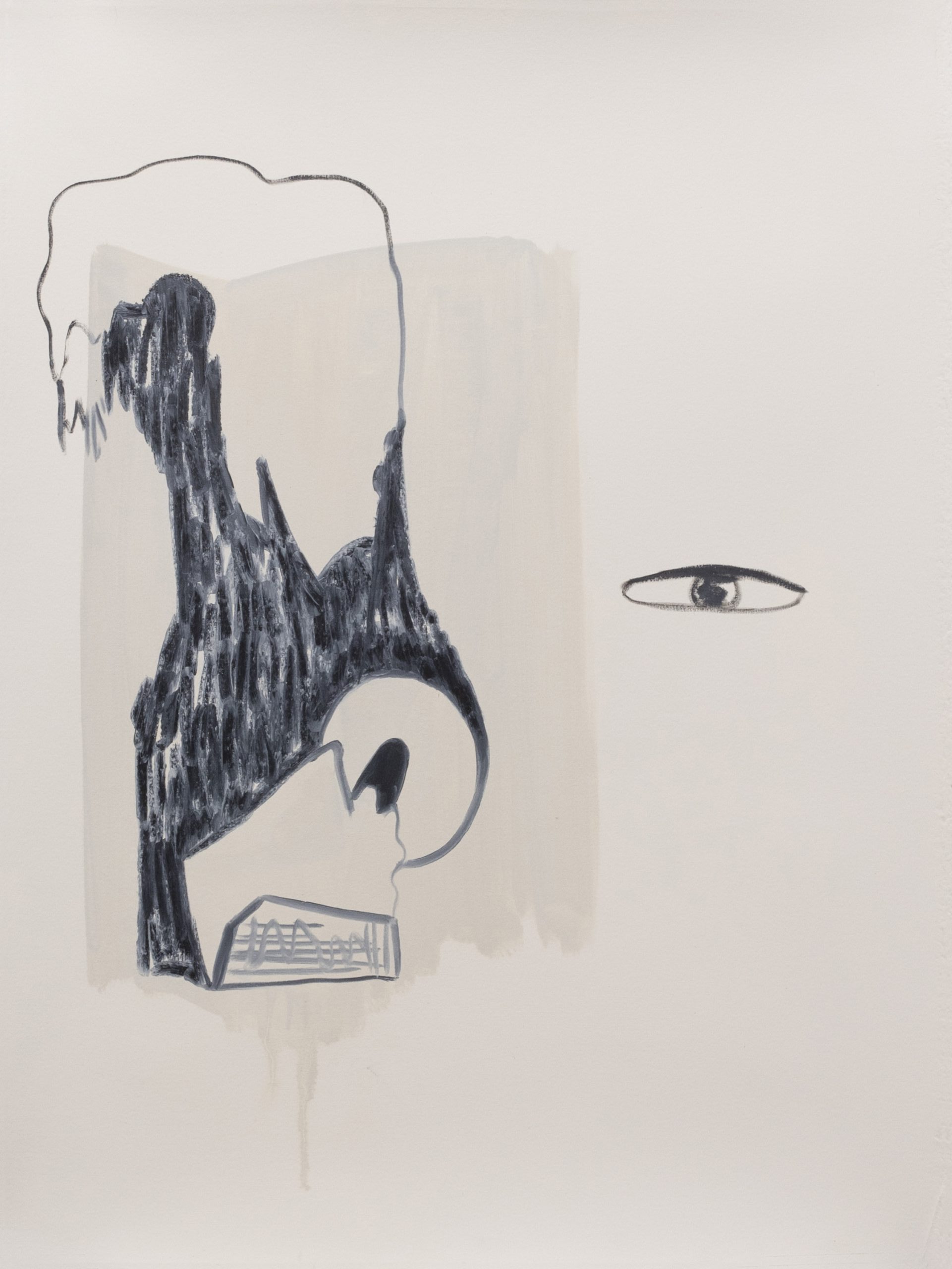

Quizás no nos volvamos del todo indiferentes, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Oil and collage on canvas + objects (paper glue, fiberpaste, wooden egg and painted cardboard)

81.1 x 69.3 in

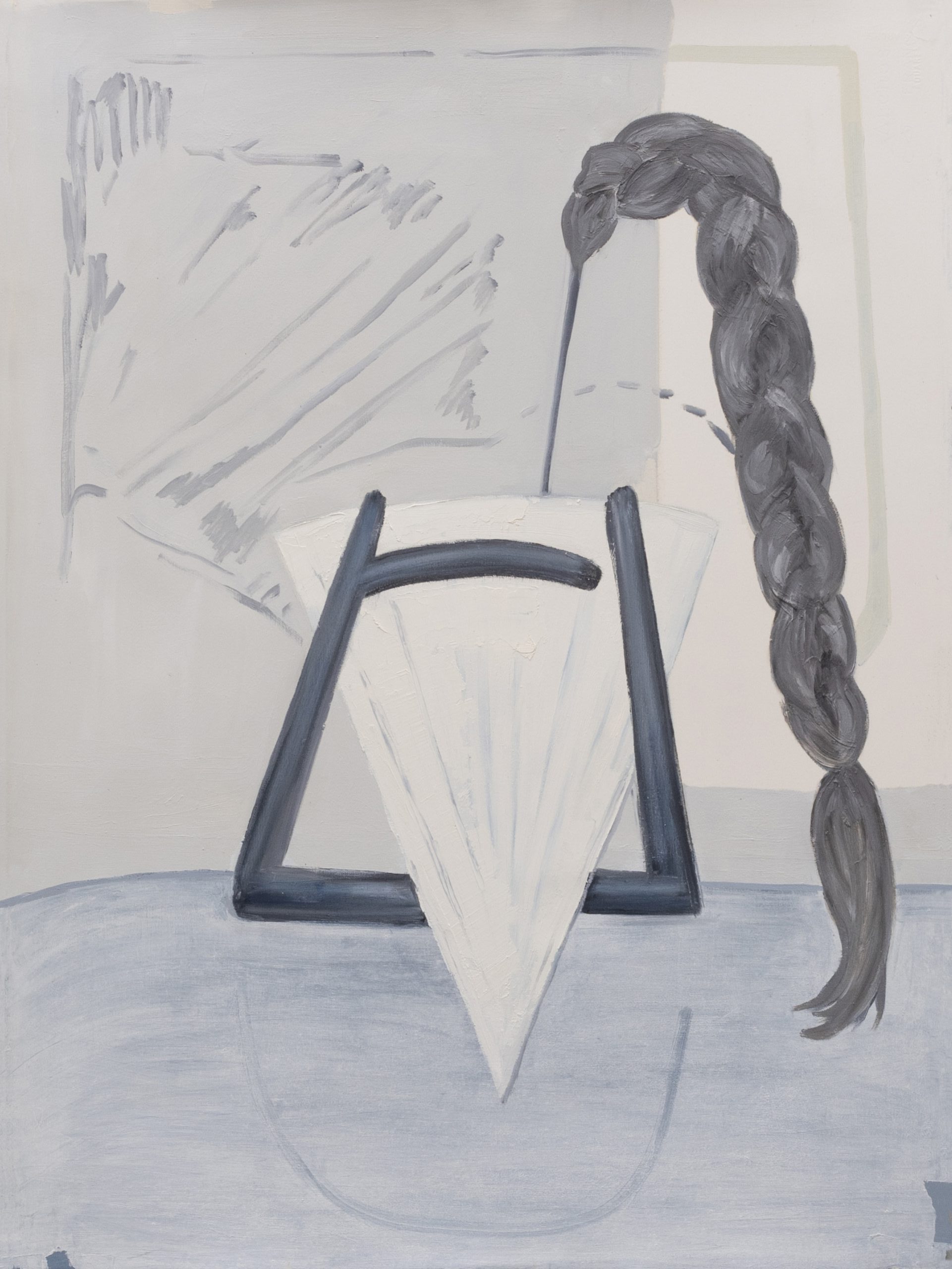

Hay que andar liviana en este mundo, o no, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Oil on canvas + object (painted cardboard)

78.7 x 77.2 in

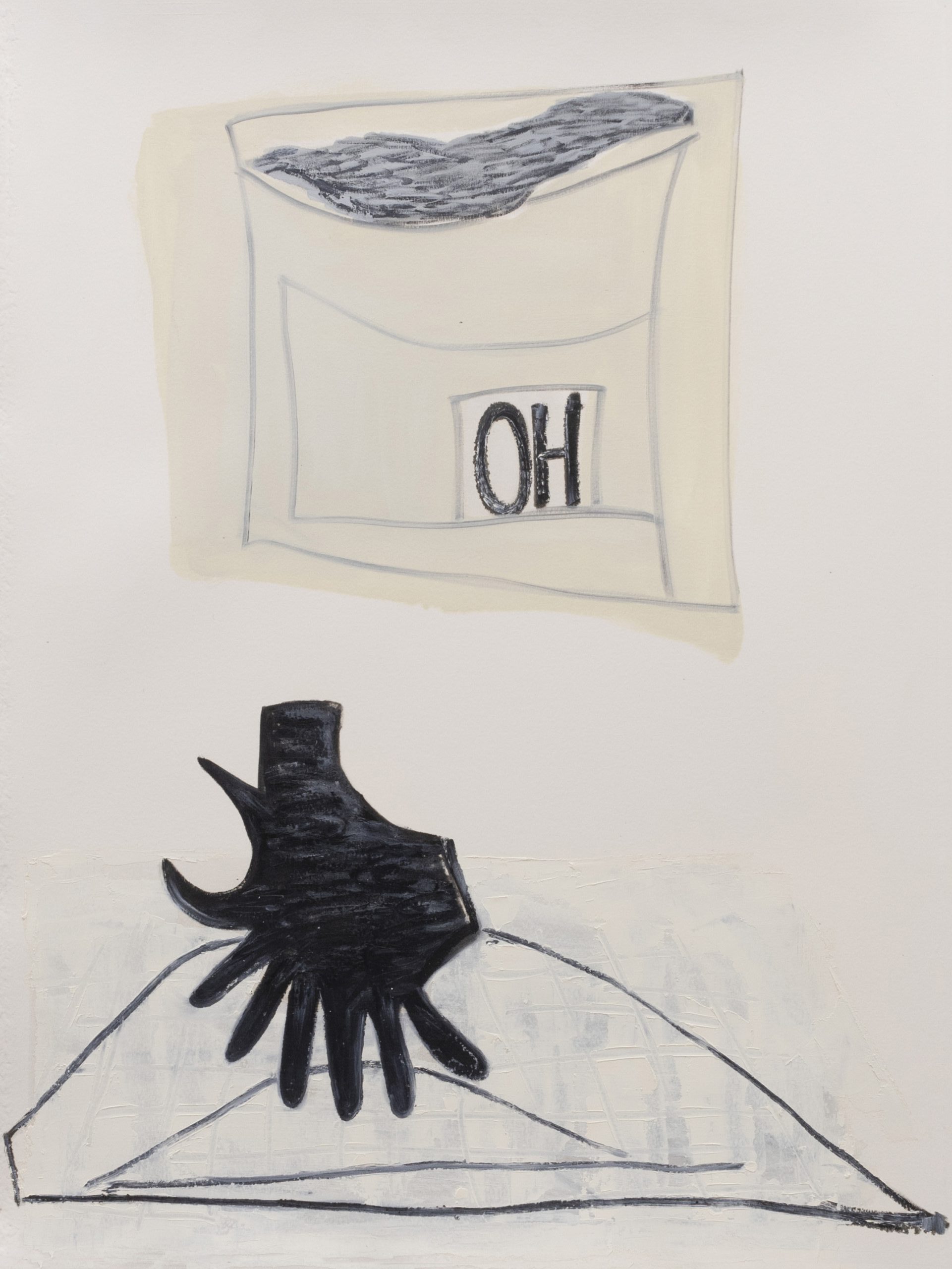

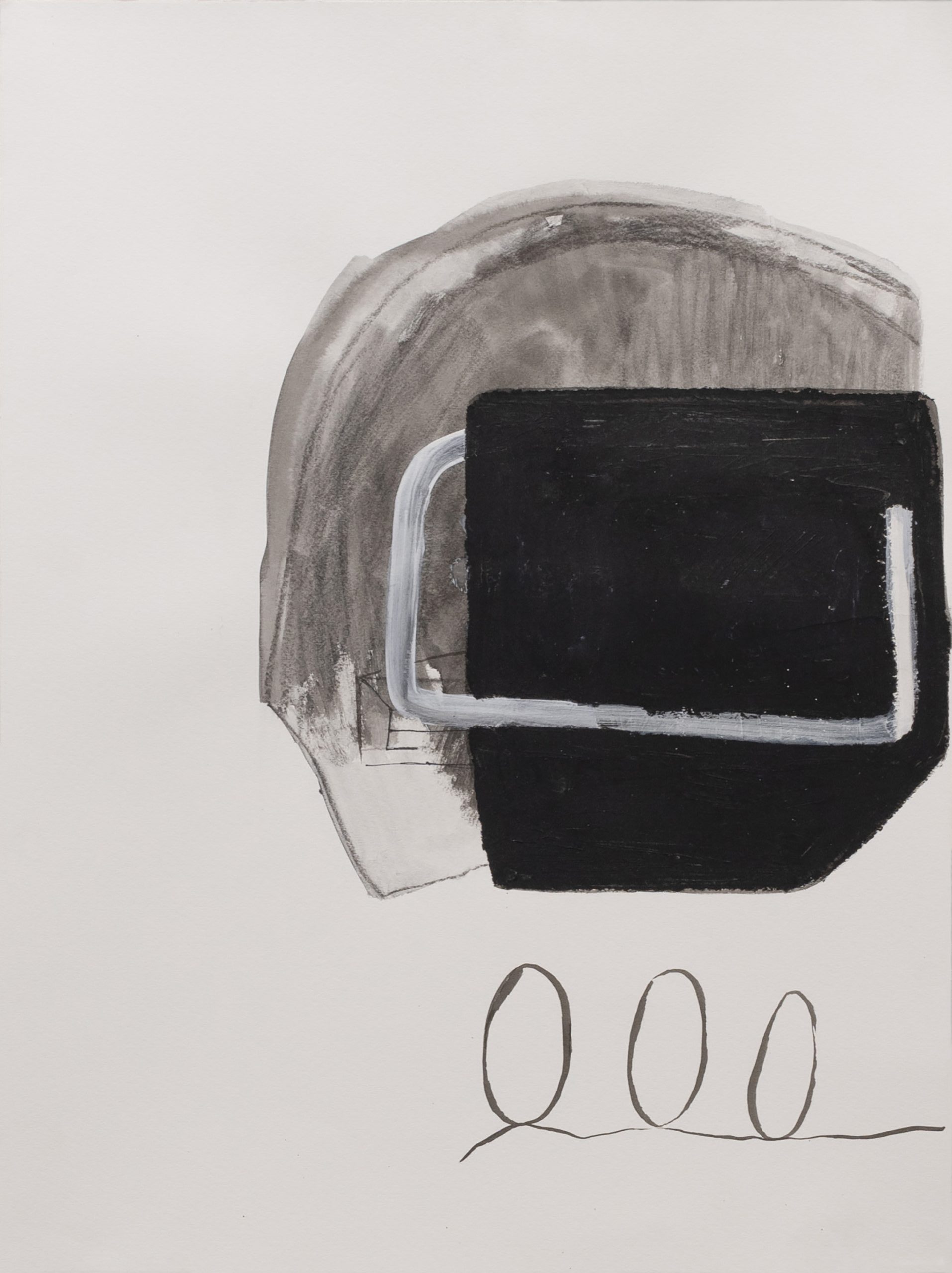

Retrato hablado, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Oil on canvas + objects (paper glue, fiberpaste and cardboard)

80.7 x 129.9 in

Gallineta #1, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Paper glue, fiberpaste, wrought metal and concrete

51.2 x 7.9 x 2.8 in

Gallineta #2, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Paper glue, fiberpaste, wrought metal and concrete

51.2 x 7.9 x 2.8 in

Gallineta #3, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Paper glue, fiberpaste, wrought metal and concrete

51.2 x 7.9 x 2.8 in

Huevo objetivo, 2023

Sofía Quirno

Plastic, wood, paper glue, fiber paste and marker

11.8 x 3.9 x 3.9 in

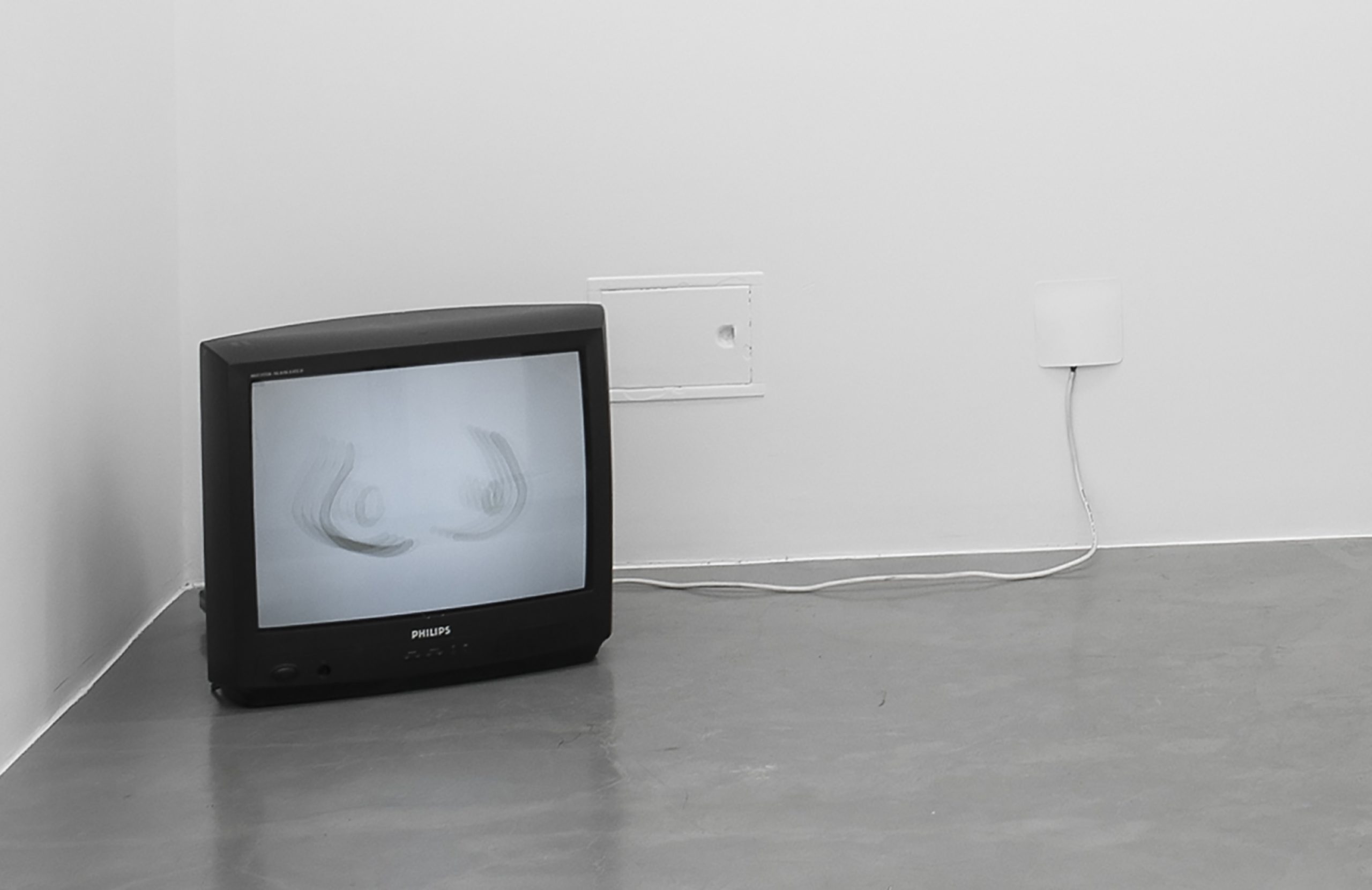

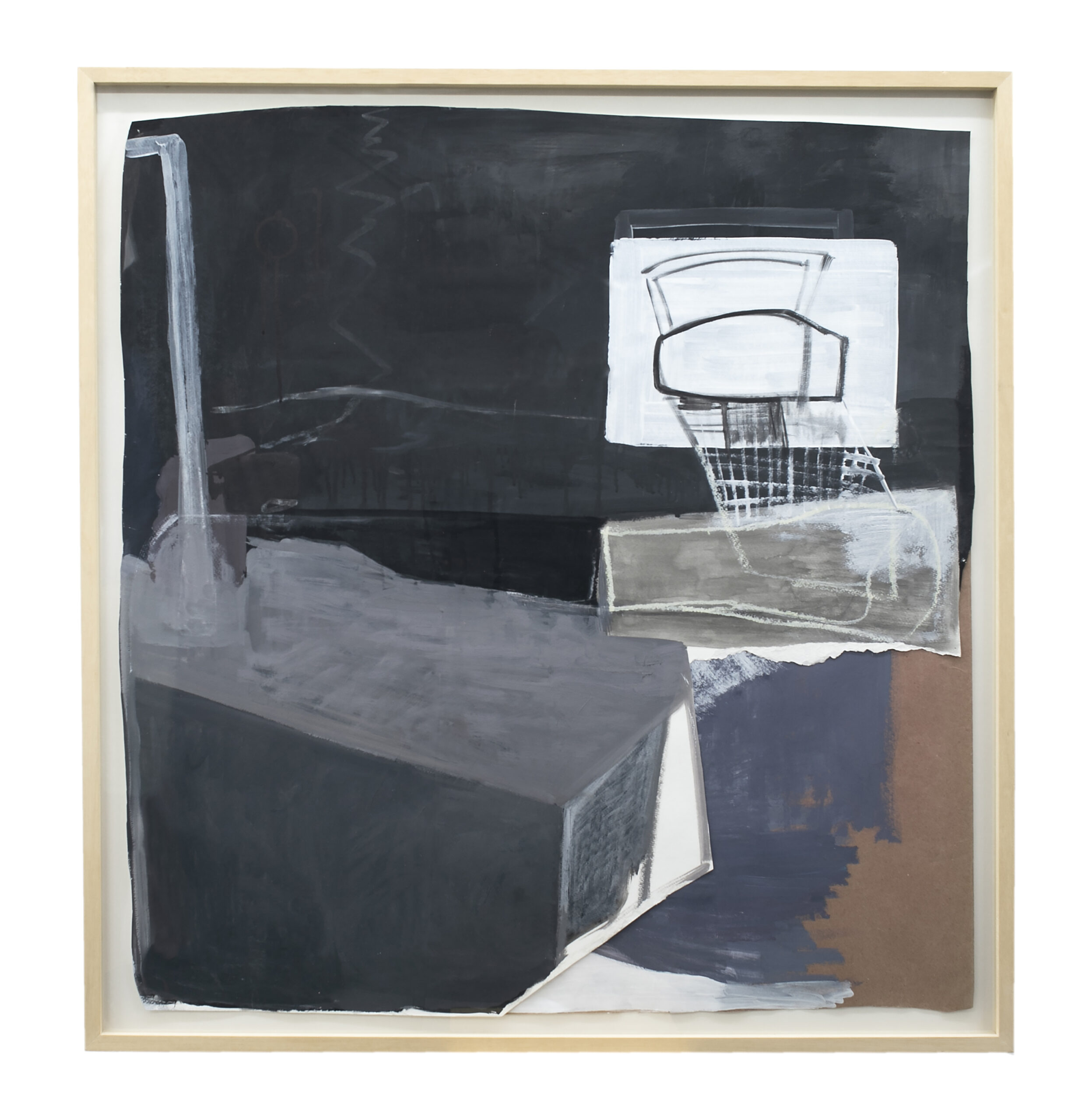

backroom view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

backroom works

Garza. Series Bye black bird, 2022

Sofía Quirno

Metal, fiber paste, oil, tree branch, and linoleum

43.3 x 11.8 x 7.9 in

TEXT

The Egg and the Chicken

By Laura Hakel

“I always think my body is Avant Garde,” Sofia Quirno told me one day in her studio in New York while leafing through the notebooks of drawings and collages she worked on over twelve years ago. They feature eggs doing balance acts—standing on pedestals or doing choreographies of winding lines that don’t seem to know where they are headed. The question that resonated throughout our conversation was how to program and how to reprogram the imagination of the body in relation to its capacity to gestate.

It is sometimes necessary to rewind to take stock of our obsessions, whether passed down, imposed, or innate, obsessions that the body metabolizes in its process of renewal. Two years ago, Sofía Quirno began to reexamine her notebooks. She tore out whole pages, cut out parts, and ripped paintings only to put them back together to create the sketches for the works now on exhibit in Hache gallery. The chickens, clocks, metronomes, slashes, and ovals in El cuerpo es Avant Garde form a constellation of ideas tied to bodily cycles.

Quirno’s work has a fragmentary logic. Her process entails taking from her daily life phrases and images that resonate in her mind and her vision, expressions in English or in Spanish, say, that she hears while walking down the street, watching TV, or listening to the radio. She also incorporates spaces she sees on her way to work, references to other artists, as well as objects found in her dreams or produced by her imagination. All of those bits and pieces end up in her notebooks. With them, she creates enigmatic and somewhat unreal images, almost like a sort of exquisite corpse of what filters through the body and perception over the course of the day.

In the painting Hay que andar liviana en este mundo, o no [You Have to Travel Light through this World, Or Do You?] (2023), two earlier works are layered to give shape to an oval body in the midst of a moonscape. In Retrato hablado [Spoken portrait] (2023), eggs painted in cold tones flow copiously out of a snail-like element. One half of the canvas Quizás no nos volvamos del todo indiferentes [Perhaps we won’t become completely indifferent] (2023) depicts a construction that looks like a henhouse with blind windows and romantic phrases such as “you and me” in graffiti-like print, and the other an intelligible space. The comingling of dualities, the interruptions, and the unstable compositions in Quirno’s paintings suggest promises and discomforts, freedoms and frustrations regarding how subjectivity, imagination, and expectations about the reproductive time of the body are shaped.

At play in Sofía Quirno’s studio practice is the joining of different materialities to compose immersive installations where the elements in the space resonate in one another.

The large-format paintings are mounted on stretchers that act as shelves, holding up small pieces of other paintings or of sculptures. Alongside the objects and animations in the gallery, the paintings formulate tensions between macro and micro spaces; they signal relations tied to the mobile, the dynamic, and the frozen, and propose paradoxes between things that stand on their own and things that must be propped up.

At the height of the surrealist avant-garde, Francis Picabia compared the body to a machine, making ironic reference to the productive automatism that came with modernity. Sofía Quirno’s El cuerpo es Avant Garde, meanwhile, posits that the body precedes the knowledge of reason. This show is an invitation to see how the flow of vital processes negotiates with the mind, with the spaces we inhabit, and with images. At this very moment, Sofía must be getting on the plane for Buenos Aires, her works scattered through her luggage. “Everything I do can be folded, transported, or stored. My art has to be rollupable; it is like a tent I take with me.” Sofía Quirno’s painting is her home, one where affirmations and contradictions live side by side.