TODO ERA FANTÁSTICo

GABRIEL BAGGIO

TEXT BY JESU ANTUÑA

MAR 25. — JUN 28. 2025

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

works

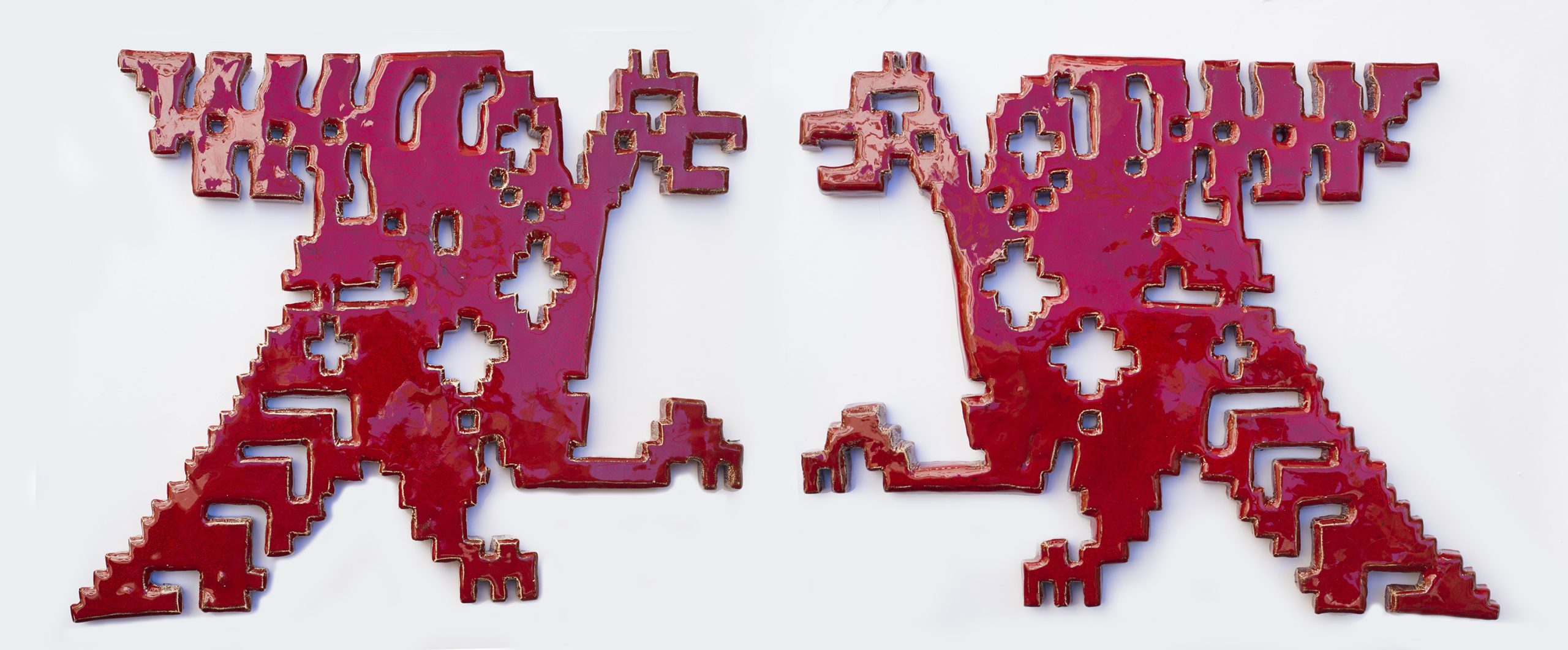

Las herramientas de Selva, 2025

Gabriel Baggio

Enameled ceramic with gold luster

74.8 x 51.2 x 19.7 in (approximate measurements)

Edition 1 of 1 + A.P

BACKROOM works

Los cisnes del mal (Palazzo Landolina a Notto). Series Las flores del mal, 2024

Gabriel Baggio

Enameled ceramic with gold luster

31.5 x 47.2 x 3.9 in

Edition 1 of 3 + A.P

Las flores del mal (Scuola Grande Di San Rocco a Venezia) Boceto. Series Las flores del mal, 2024

Gabriel Baggio

Enameled ceramic

15.7 x 9.8 x 1.6 in

Edition 1 of 10

Los ojos del mal (Duomo di Siracusa). Series Las flores del mal, 2024

Gabriel Baggio

Enameled ceramic

19,70 x 43,30 in

Edition 1 of 3 + A.P.

TEXT

Midnight, Again

by Jesu Antuña

[I am] a force of the past,

more modern than any modernist.

Pier Paolo Pasolini

We live in cursed times,

but that does not mean we should feel

that life is any less beautiful—though

death does weigh heavy.

León Rozitchner

In a patio with a thousand shades of green and mountain view, a group of weavers turns threads into blankets, ponchos, and scarves. Selva Díaz, the matriarch, inspects the work of the others, most of them men. Her children and grandchildren join in the task, and La Negrita, Selva’s cousin, laughs at the antics of the young men who have come home late from a party somewhere. Everyone is seeing to the daily toil of weaving llama, sheep, alpaca, and vicuña wool. In Londres, Catamarca province, a learning process comes to an end, an education Gabriel Baggio had begun much earlier, when he was a boy who would wake up to delightful sounds and bodies gathered together. He once said that the archive of the knowing-making processes he has learned resides in the body. The people he works with are embodied archives of ways to cook, weave, carve wood, and build an adobe home—crafts by no means immediate, trades passed down from one generation to the next in a patient exercise of listening and exchange that can take weeks, months, years. When Baggio comes into contact with that archive, he generates the recovery and transmission of interlinked knowledges.

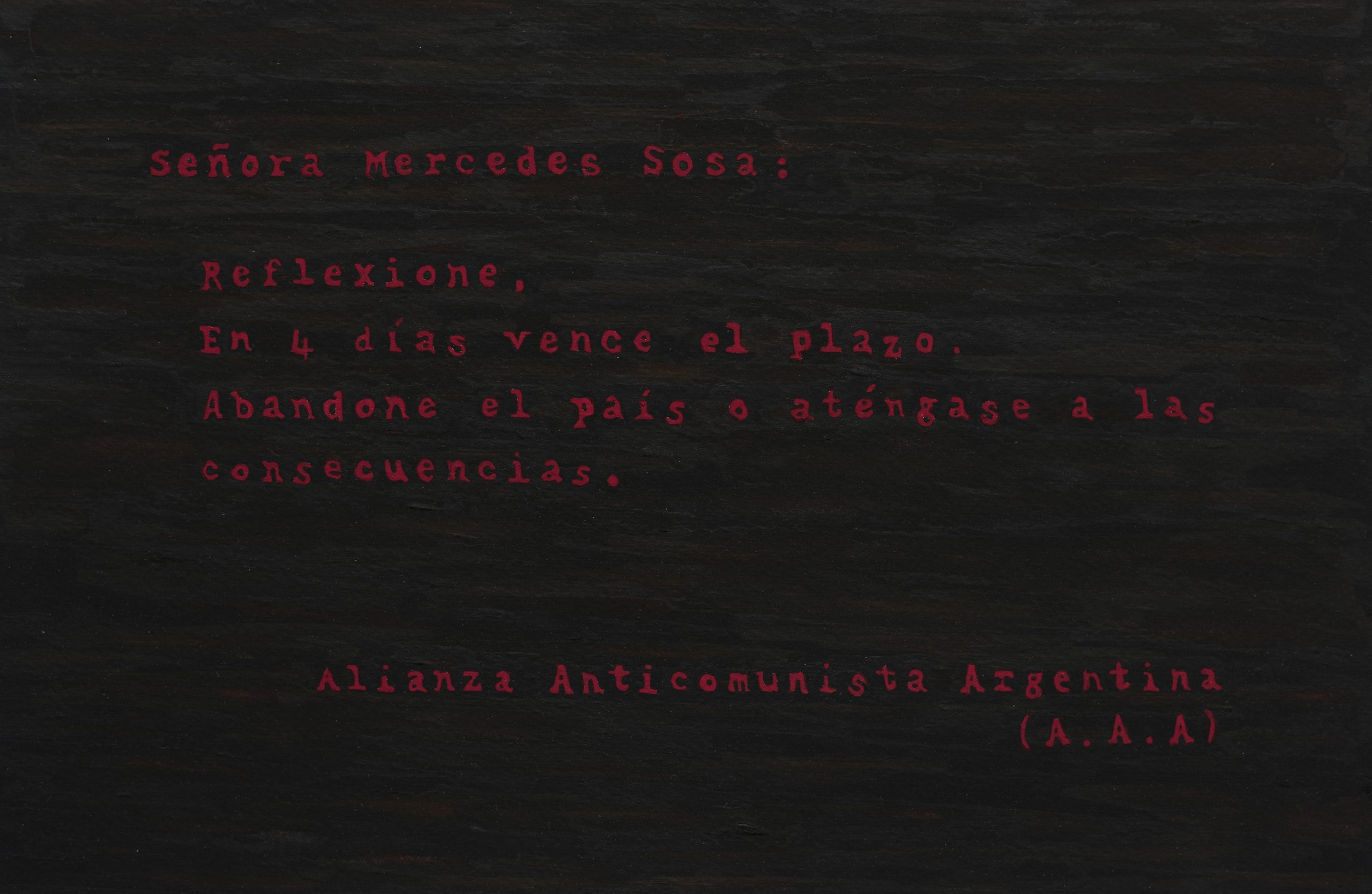

Some months before the trip to Catamarca where he came into contact with the archive of the women weavers, something startling surfaced from his embodied archive—a jarring and involuntary return of the past. In a hallucinatory procedure, a foundational memory emerged: the concert Mercedes Sosa gave at Ópera theater in Buenos Aires in February 1982 in a brief lapse between periods of exile. Sosa performed thirteen concerts over the course of ten nights. Baggio saw Sosa twice, the first time in the flesh when he a child (oddly, his parents let him go alone), and the second over forty years later, when he returned to that concert in his mind’s eye the hundreds of red carnations that welcomed the singer who had had to flee the country in 1978, after receiving death threats and, worse still, being banned from exercising her craft.

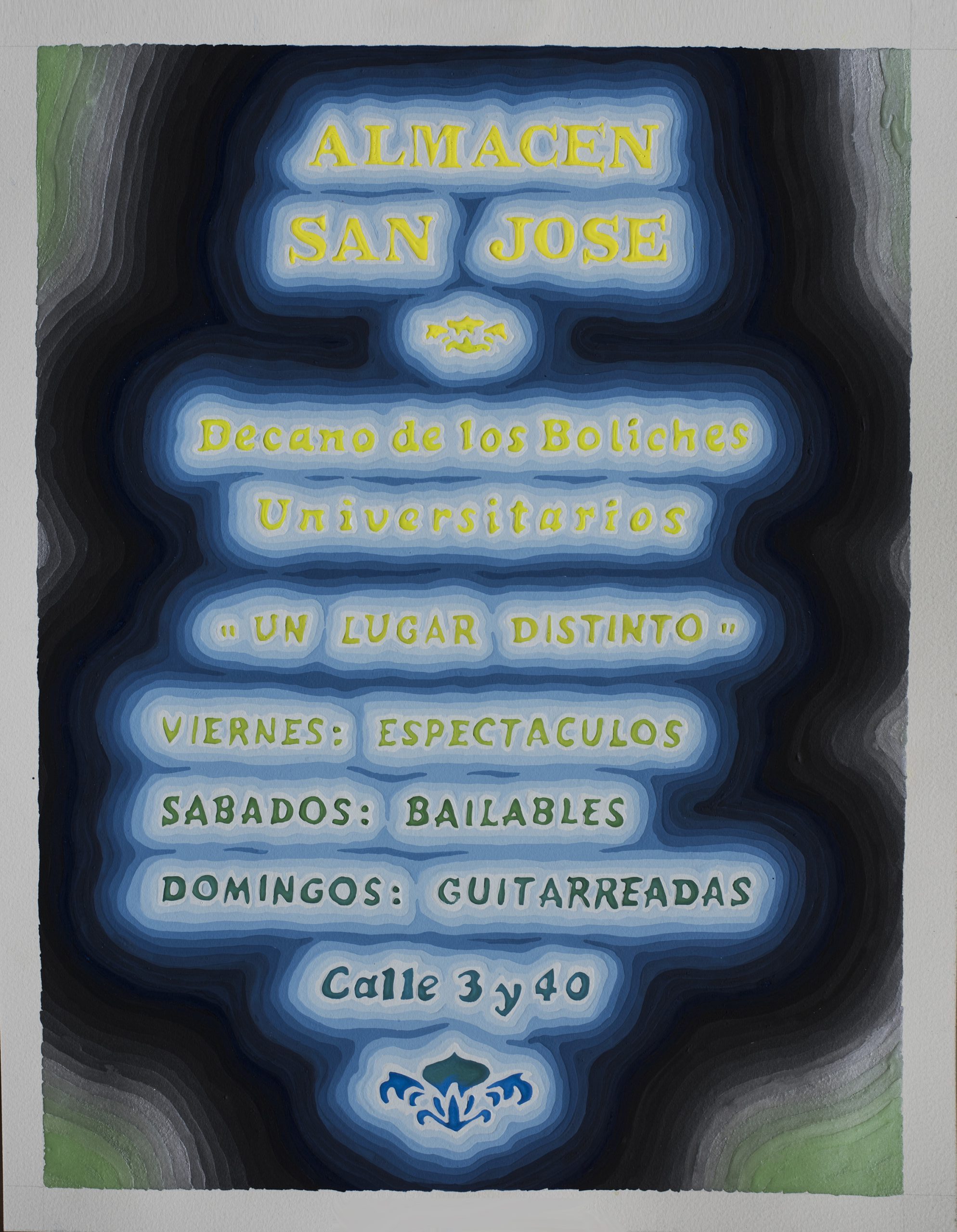

Mercedes’ last concert before her first period of exile was on October 18, 1978 at the Almacén San José, a venue in La Plata frequented by students and folk musicians from around the country. “You could write the history of Argentine protest songs from the sixties and seventies,” states Sergio Pujol, that is, on the basis of the artists who played at the Almacén, which he calls “our Balderrama” in reference to the folk venue in Salta province immortalized by Manuel J. Castilla and “Cuchi” Leguizamón. That night in La Plata proved tragic. The police crackdown got underway when Mercedes sang Cuando tenga la tierra and Canción con todo, two songs banned by the military dictatorship’s censorship apparatus. As soon as she did, the police raided the Almacén and carted away the singer and her son, along with the musicians accompanying her, the owners of the venue, and the over two hundred and fifty people attending the show. It took a number of police vehicles to get all of them to the station. They were accused of having participated in “an act of ideological diffusion,” a prohibited act of transmission that, according to the authorities, had to be cut short.

La Plata, October 18, 1978

SIR:

It is my duty to inform you in the attached Memorando D.G.A “R” N° 2353 issued by the Secretary General, accompanied by Radiograma N° de MSG 7382 “ICIA” N°1037/78 of the Ministry of Interior that, under the guise of folk and art festivals in which MERCEDES SOSA, MIGUEL ÁNGEL MERELLANO, and FRANCISCO HEREDIA took part, Marxist ideology has been spread, one case being the festival held in Rosario, Santa Fe province on September 21, 1978.

Without further ado,

Dr. Jaime L. Smart

Buenos Aires province Ministry of Internal Affairs

Mercedes was held incommunicado for over eighteen hours. She endured abuse at the hand of the detaining authorities, regardless of what police reports and contemporaneous articles in the press said. A few days later, she was supposed to play a similar repertoire at the Teatro Lasalle in Buenos Aires, but the concert was cancelled at the last minute because of a bomb threat. “I am leaving because I am out of work,” they say she said when she departed in exile, though a government memo asserted that if she sang she would be detained. Culture was a prime target for crackdowns on the part of the military and the police. It should come as no surprise, then, that just two years before, Jaime L. Smart, the one who signed the singer’s arrest order, had appealed to Ramón Camps and Miguel Etchecolatz: “Subversion, sirs, is ideological, and subversives lurk everywhere in the cultural sphere.”

Though stormy as exile always is, Mercedes’ European years were marked by artistic growth and international recognition. Just two years after she left Argentina she was introduced at a concert in Switzerland as “the voice of a continent.” Before that same concert, she stated “nothing banned that has found its way into the people’s heart will ever be forgotten.” Sorrow over her banishment rang out in the first chords of Piedra y camino (“Sadness has a hold on my soul”) and woeful passions in the song by Atahualpa Yupanqui she performed (he had also been expelled from the country). Her pilgrimage through distant lands and her desire to come home were center stage in one of the songs she sang the night of her return: Fuego en Animaná by César Isella and Armando Tejada Gómez:

Si yo me voy, conmigo irá

todo lo que soy.

Lejos de mí, lejos de aquí,

yo no seré yo.

Déjenme estar, de solo estar,

viendo el sol volver.

Yo quiero ver en mi país

el amanecer.

Her return was not easy either. A series of concerts at Premier and Coliseo theaters were cancelled, and she continued to receive threats until the opening chords of Los hermanos, also by Yupanqui. Her performance of Los hermanos—a song to freedom and labor in memory of the dead—took place some months before the Malvinas War.

The night of her return, the one where she gave the concert Baggio attended, Mercedes fluctuated between tradition and openness to new genres: the rock of Charly García and León Gieco, the Latin American sounds that nourished her during her exile in Europe, and the influences (and even physical presences that night) of Piero, Antonio Tarragó Ros, Rodolfo Mederos, Ariel Ramírez, and Raúl Barboza. Mercedes shattered the clean division between listeners—a political act at the time. She knew that the reign of terror had been unleased on culture in particular—she had experienced that in the flesh. Culture is, after all, a space for the production of subjectivity and for individual and collective exploration, so it had to be forced into submission. At stake in the convergence of genres and generations was the return of democracy and the groundwork for the artistic production to come. But the country could not yet take Mercedes back—the conditions were not right—and just a few days later she was once again forced to flee.

When he returned from exile in 1986, León Rozitchner spoke of the military dictatorship’s crackdown on culture. Culture, he said, is “what the free hand of war tries to do away with. Culture is where another basic power is produced—and they know that.” With those words, Rozitchner foretold many contemporary readings that point out the two-fold operation performed by the neoliberal-conservative machinery: Violence not only annihilates and disappears bodies, but also acts on the production of desire, that is, the production of subjectivities. What Rozitchner observed when he returned is the mutation that capital was undergoing in the nineteen-seventies—and Latin America was its laboratory. Suely Rolnik describes its current iteration: “Capital appropriates life itself, more precisely, life’s potential to create and transform at the very emergence of its impulse—that is, its germinal essence—as well as the cooperation that that potential relies on to execute its singularity.” That means that the operation of appropriation and fracture of vital potentials keeps new forms of life at bay, keeps them from sprouting and blossoming; it prevents the interchanges necessary for a greater articulation of collective forces. But also, and crucially, that operation materializes a production of subjectivities absorbed by consumerism and show business, where creative forces are reoriented in the direction of market interests.

At the same time, albeit in a very distant and, at that juncture, less violent land, Pier Paolo Pasolini observed a wrenching mutation in the Italian people. In Gennariello, he imagines a youth of that name to whom he attempts to impart his knowledge. What the older man comes up against, though, is a social landscape that had, since his own childhood, undergone utter transformation. At stake was not just the loss of a glorious or mythical past, but the transformation of the daily life of the people: They had lost the sense of joy characteristic of life on the outskirts the city. Pasolini sensed that the ultraconservative shifts underway were more sophisticated and harder to combat than the Fascism that had gripped Italy in his youth. He closed his eyes before the evidence that the Italian people he had so celebrated no longer existed: The language of things had changed catastrophically. Pasolini’s words on his land attest to the intimate relationship between people and culture, between the culture of a people and its genocide. Georges Didi-Huberman argues that when Pasolini uses the word genocide he is speaking of its cultural dimension. Paoilini, Didi-Huberman says, is referring to a “withering away of culture often effected through the term cultural genocide.” At stake is the masses’ total assimilation to the economic powers’ ways of living. Neither culture nor the field of desire can, then, be separated out from a new political configuration that would stave off imposed violence.

In recent years, Baggio has undertaken an aesthetic-political exploration of these violences, where desire turns into a contested space and a catalyst of temporalities capable of dislocating the present.

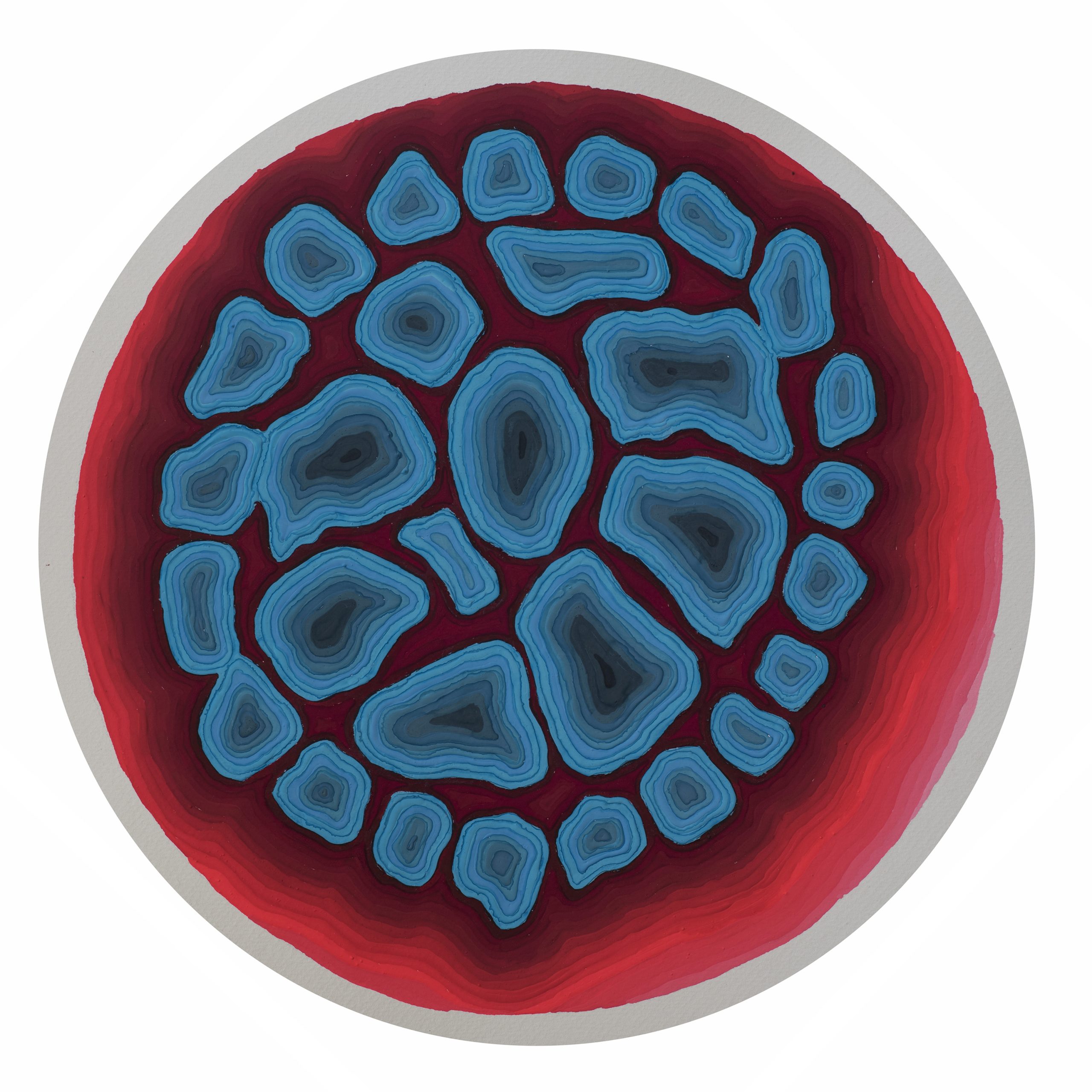

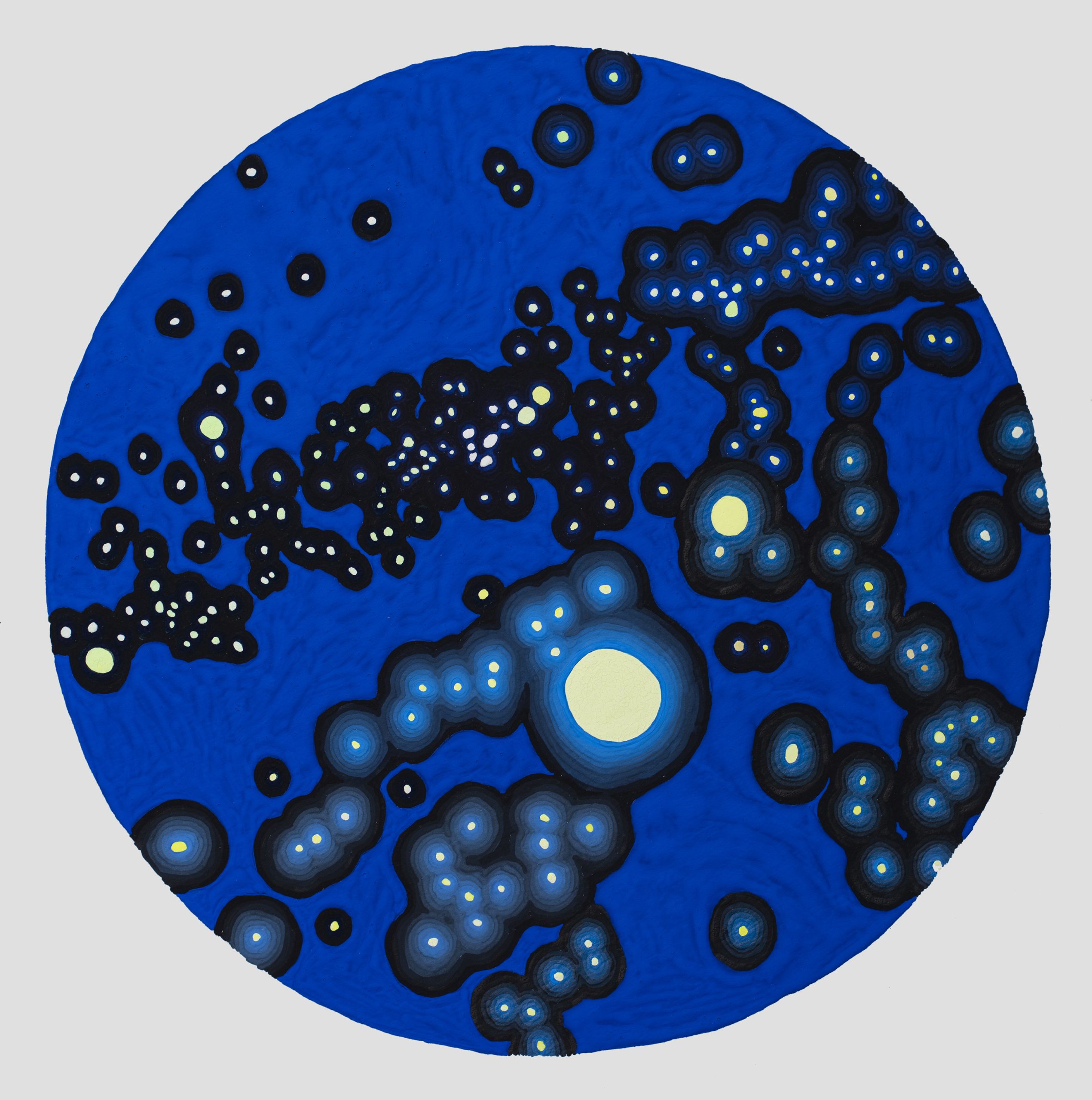

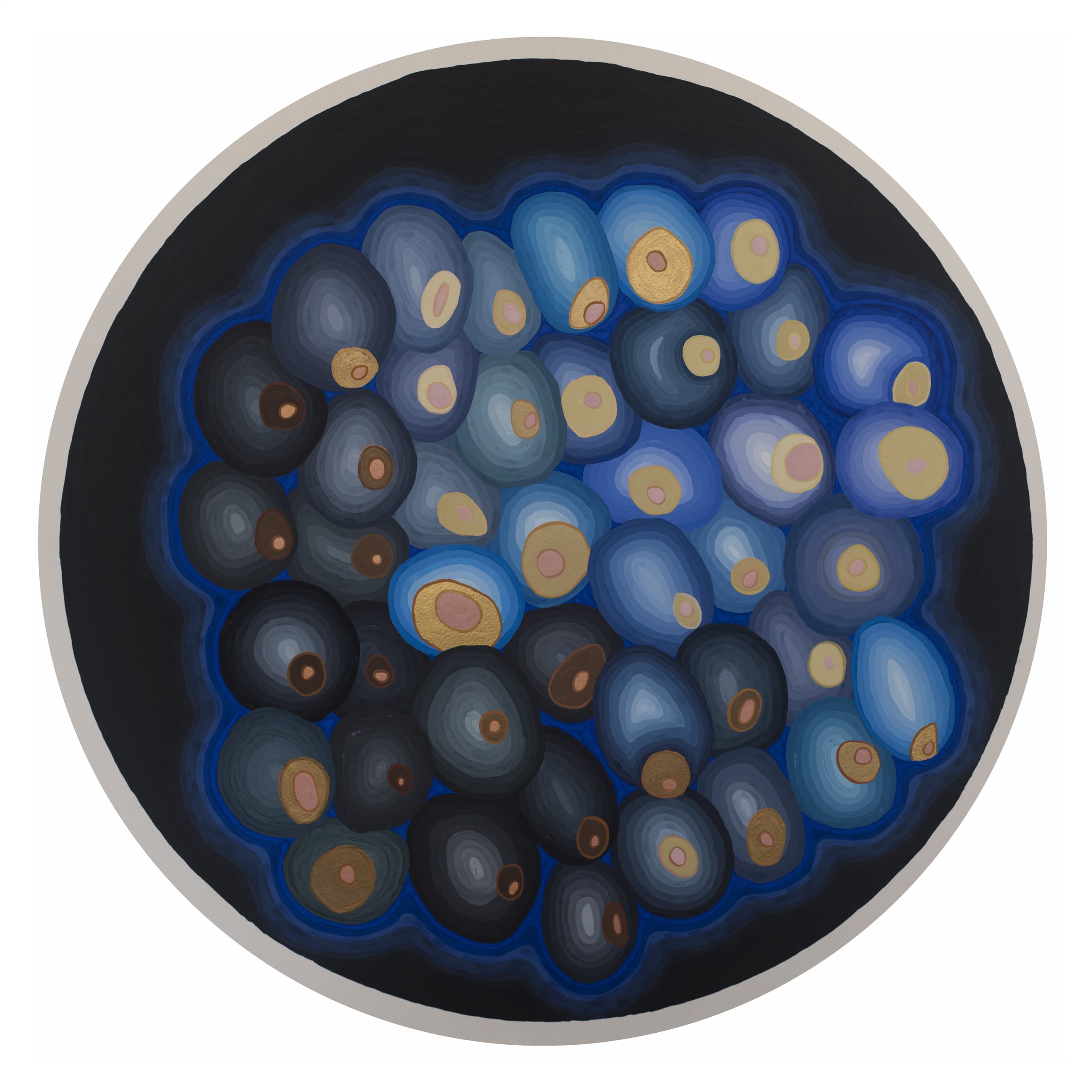

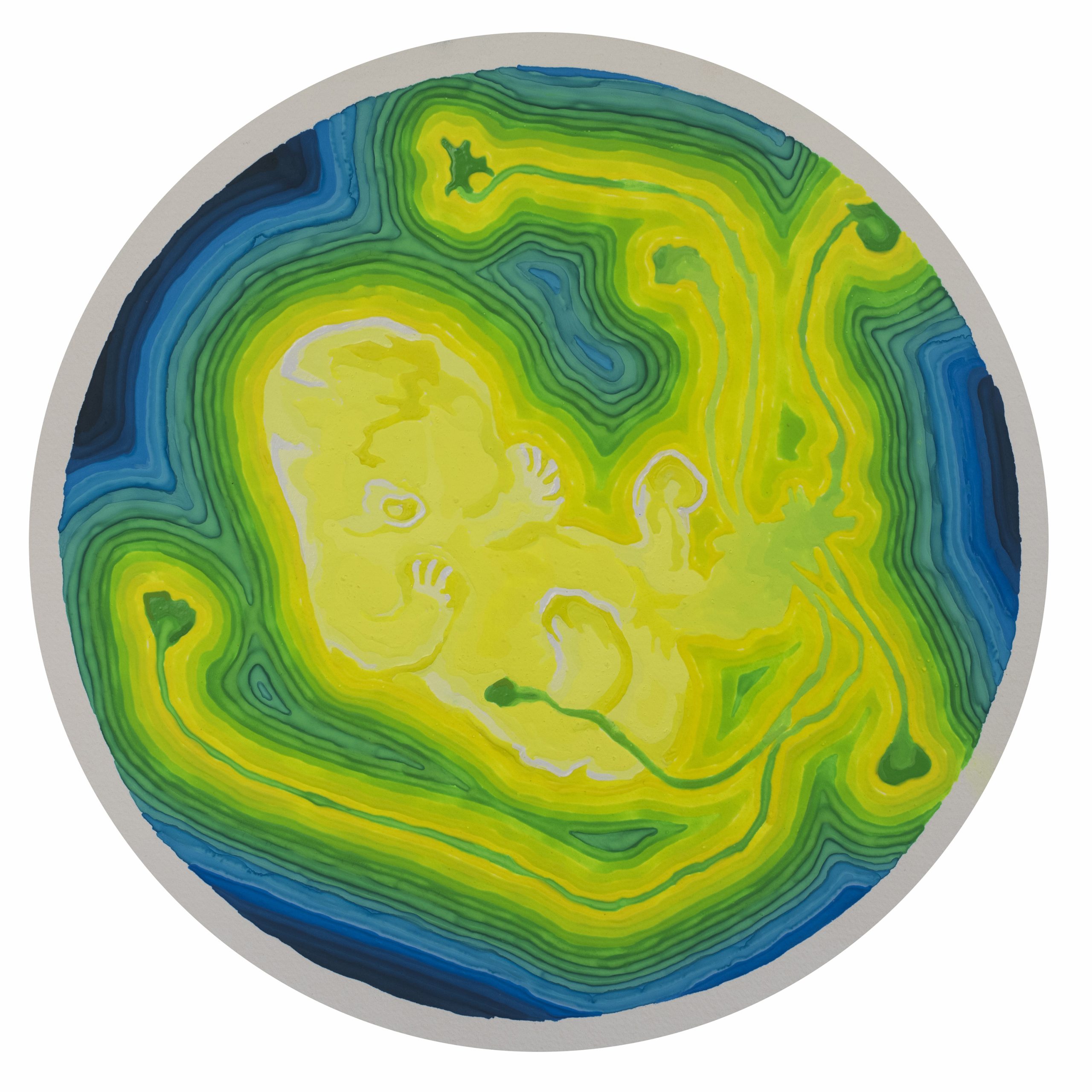

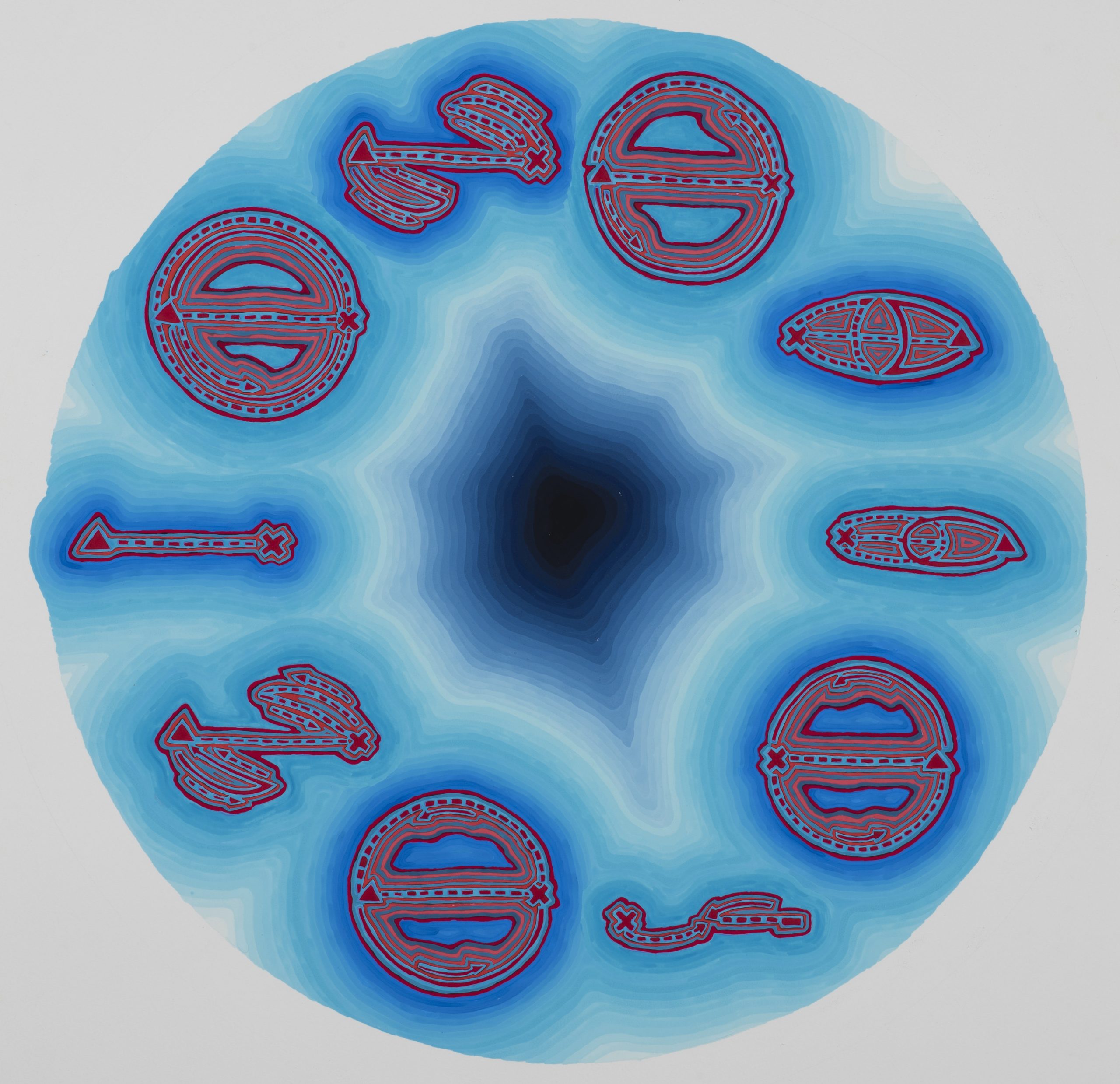

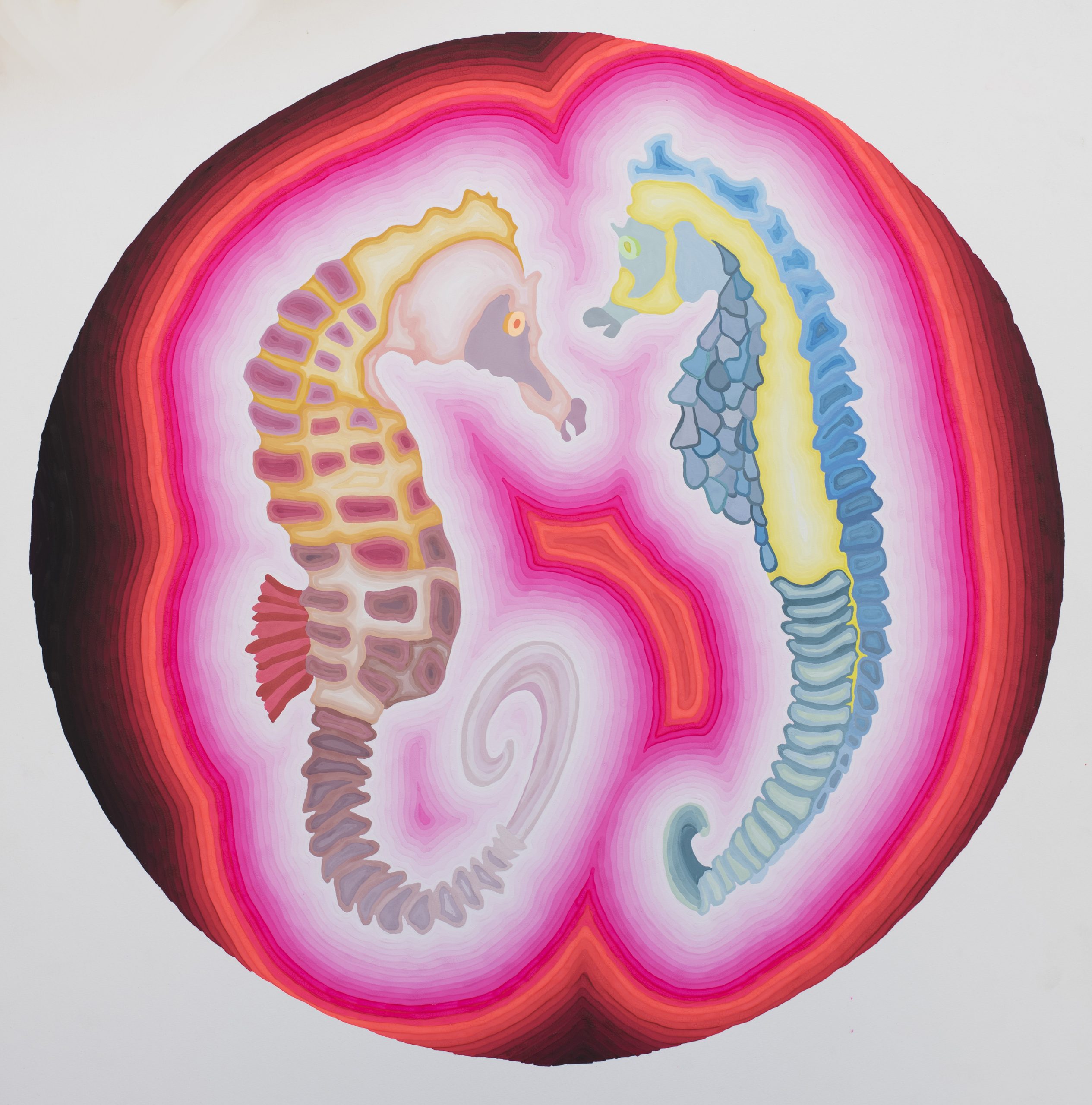

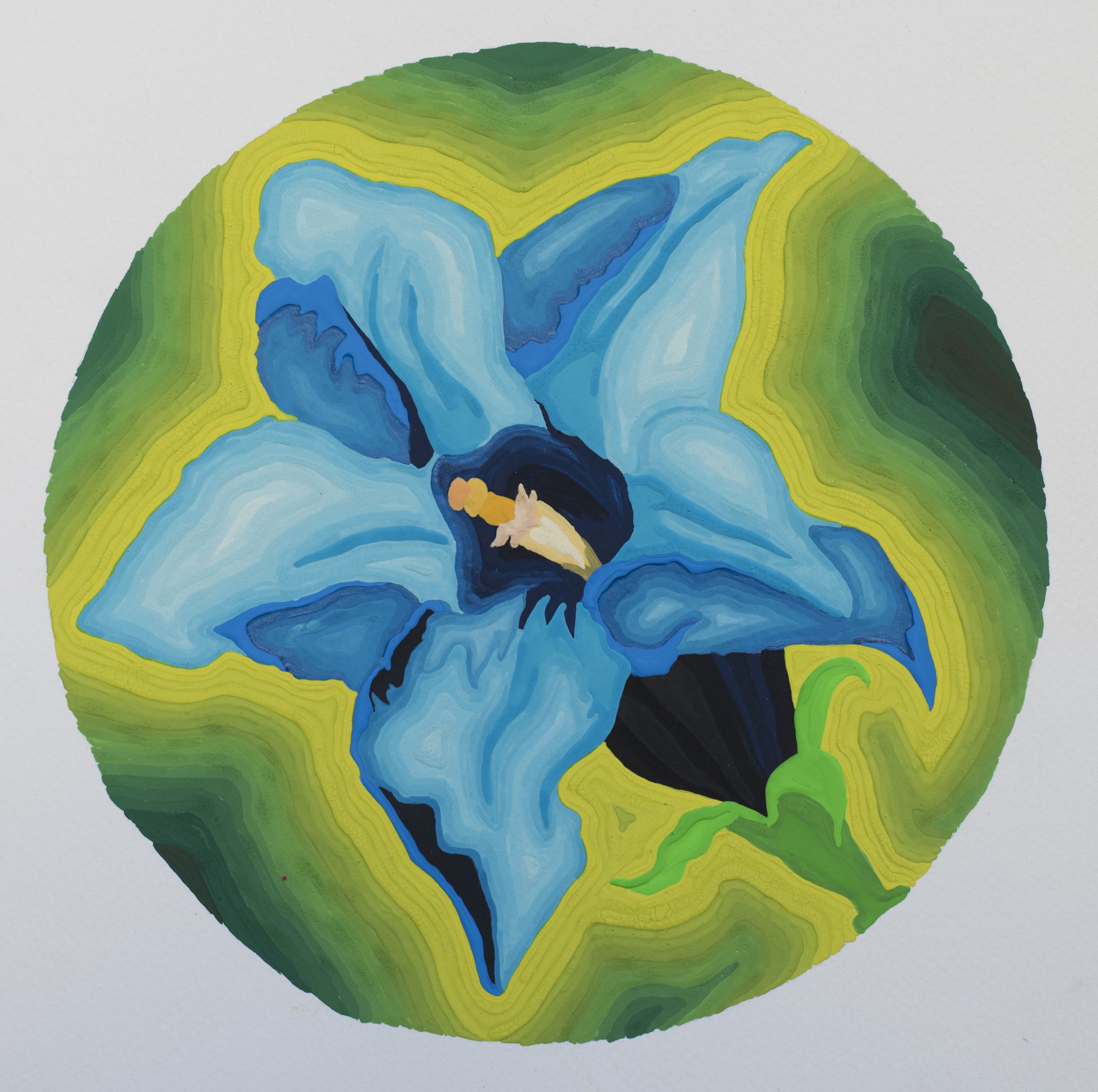

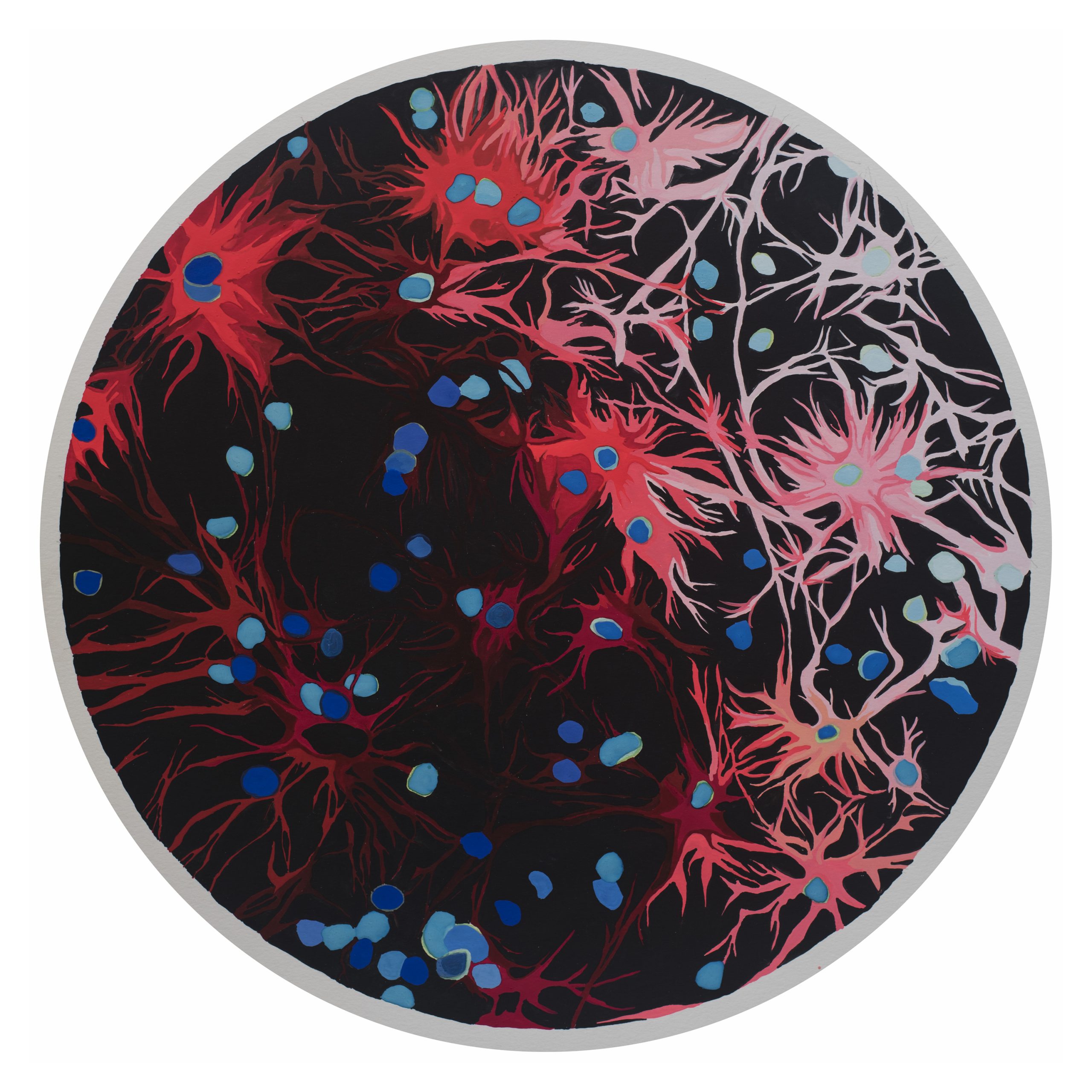

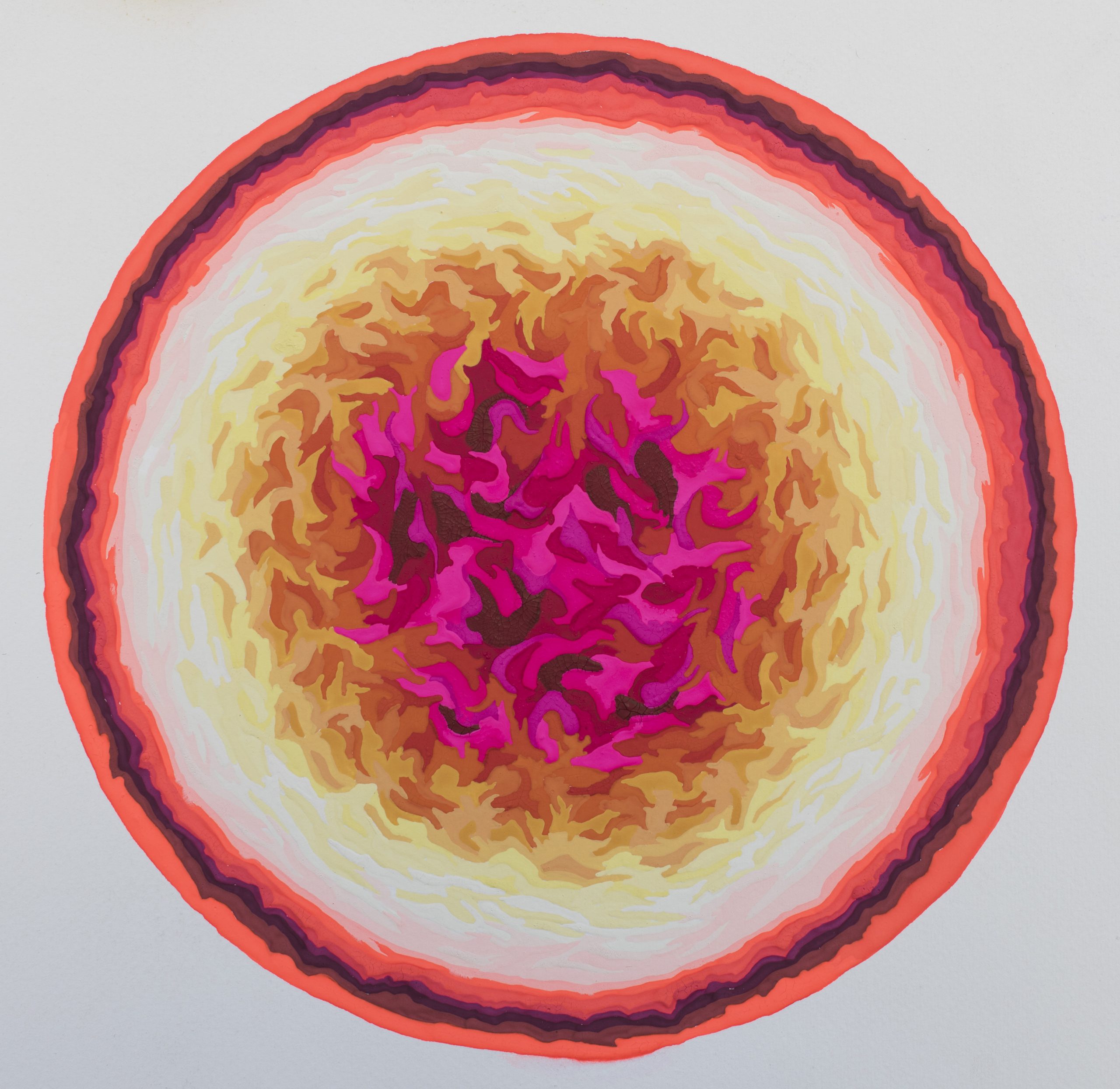

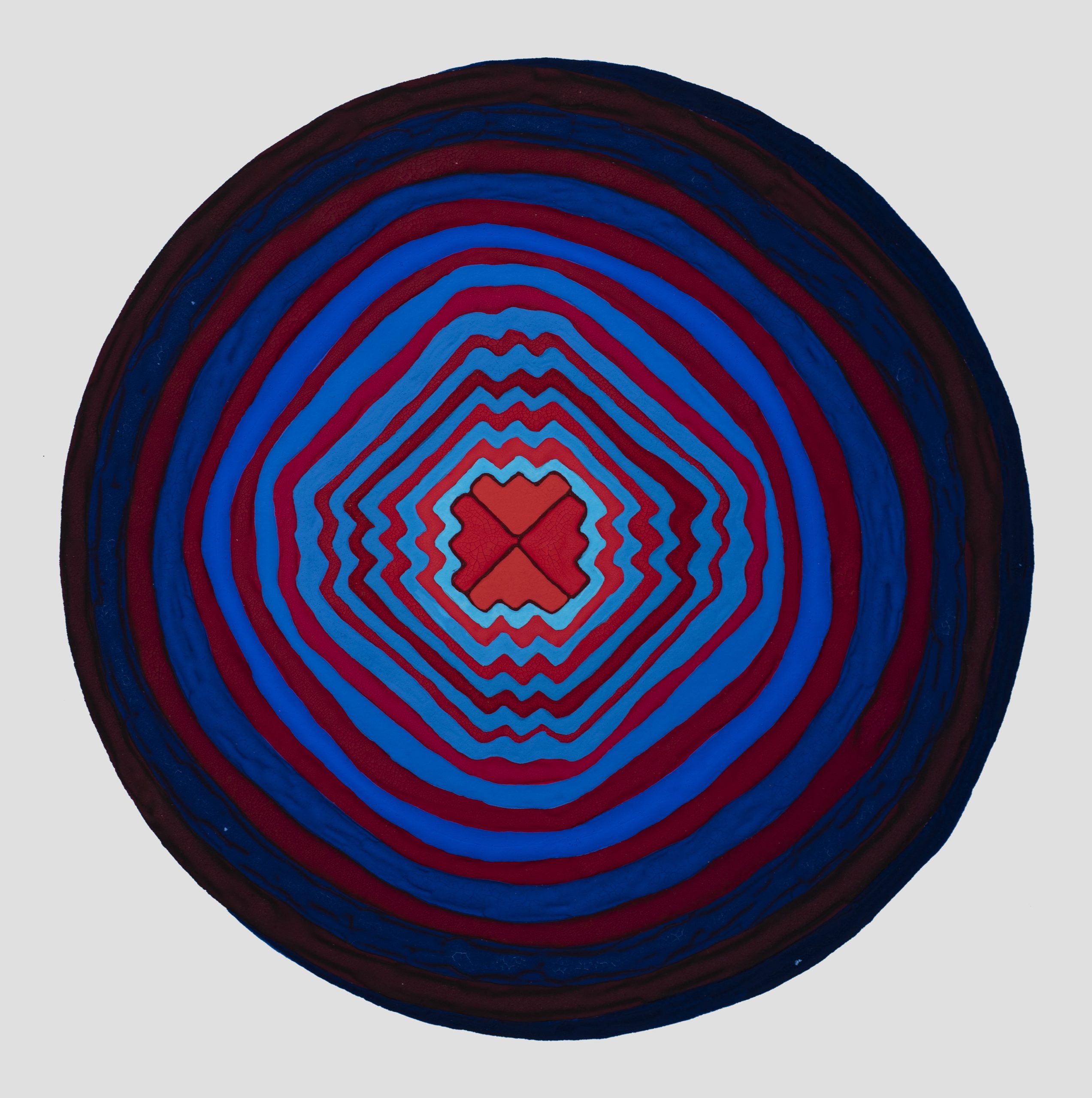

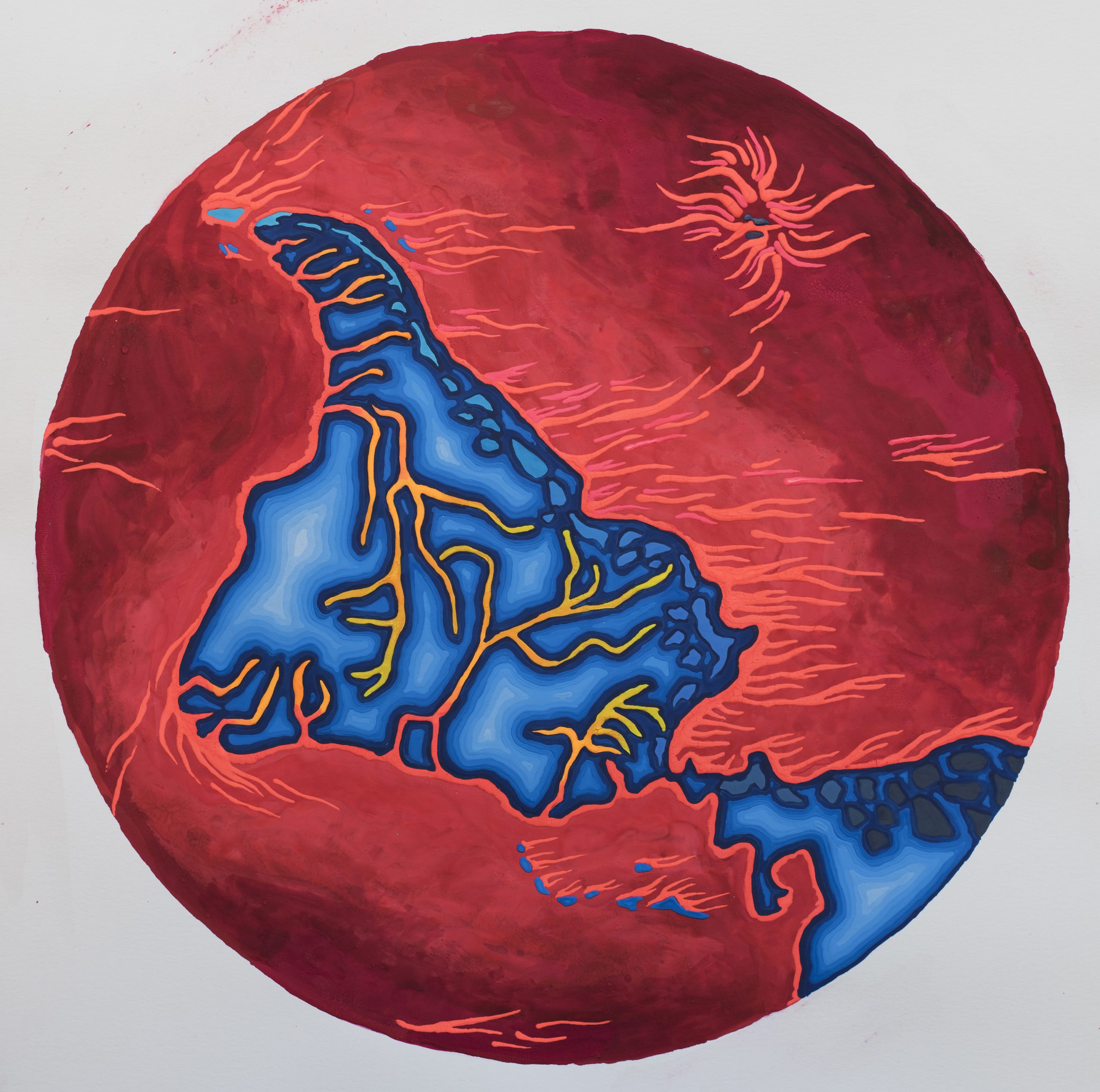

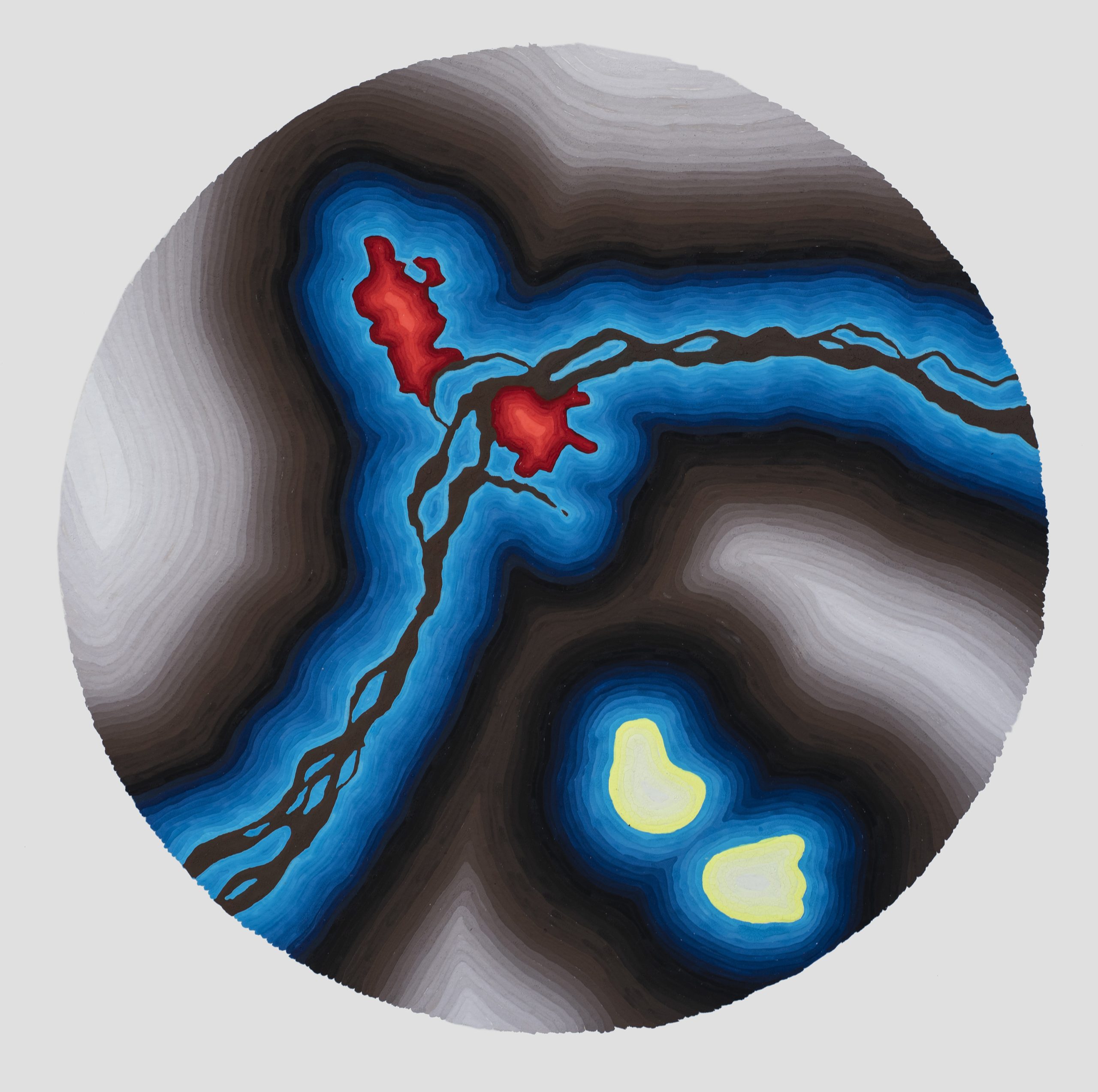

It is not by chance, then, that he returns to the nineteen-seventies and eighties to reimagine the present. On the hallucinated image of the Mercedes Sosa concert he places an image that interrogates the space of the fantastic. Potencia emancipatoria [Emancipatory Power] is a terrain open to desiring experimentation, a sexual exploration not without animal violence that enables the artist to conceive of violence in a range of ways that span from the defensive to the offensive. In it, Baggio stages the cruel pull of the animal world, at once force of life and of destruction. The work is an open space insofar as it connects with the other paintings produced for the show, one for each of the songs Mercedes sang that night of her return. While their circular format is reminiscent of LPs, the images in these paintings with their scorpion tails in strident colored and animals are by no means illustrations of the song lyrics.. Indeed, the human-animal relationship is what holds the show’s poetic-ecological images together, as is evident in works like Alfonsina y el mar [Alfonsina and the Sea], Los mareados [The Lushes], Sólo le pido a Dios [I Only Ask of God], Duerme negrito [Sleep, Negrito], and Sueño con serpientes [I Dream of Snakes].

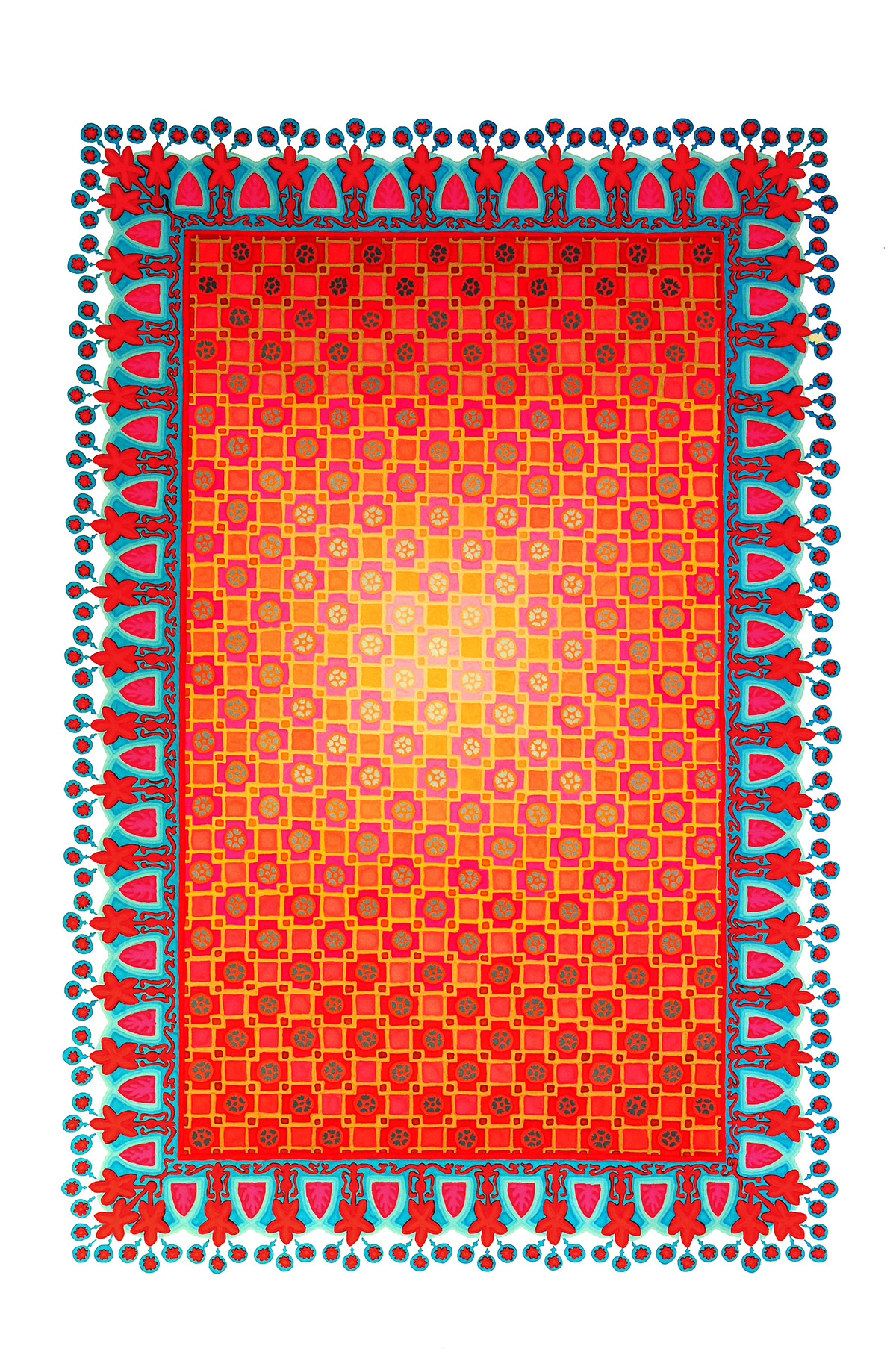

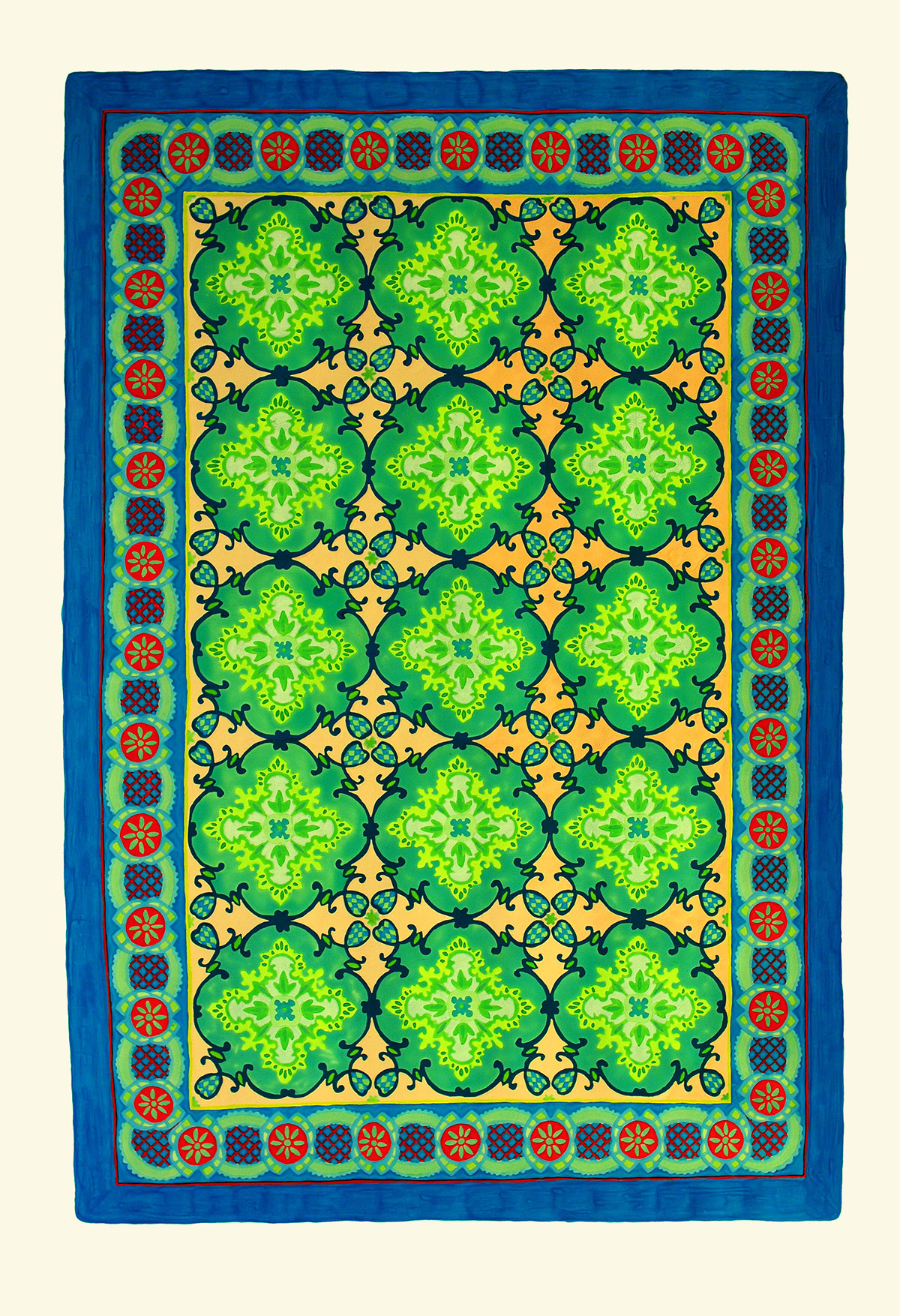

Animality also makes itself felt in the “eagle poncho,” as the poncho Mercedes wore at a number of concerts, including the one on the night of her return, is known. The poncho was produced using the ikat weaving technique practiced in communities in Argentina, Mexico, Bolivia, Chile, Guatemala, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, as well as some regions in Central and Southeast Asia. Ikat weaving often yields dual anthropomorphic and zoomorphic designs and figures in a mirror-like symmetry. Mercedes Sosa’s emblematic poncho gets its name from its four red eagles. For researcher Roxana Amarilla, the bird motifs are “associated with milestones in her career, such as exile, the return to Argentina, and concerts before mass audiences.” The eagle poncho in particular, Amarilla goes on, “is enmeshed in an epic narrative that brings together resistance to the military regime and the dreams of the democratic spring.” Sosa wore at different times at least seven ponchos produced in Londres, Catamarca, each one with a different animal motif and color scheme. Baggio decided to follow in her footsteps: He and Selva Díaz, one of the most prestigious weavers in Londres, made a poncho identical to the one Mercedes wore that night, in an act that takes up Baggio’s longstanding work with the copy. The artist spent a number of weeks under the walnut trees in the patio of the Díaz family home, learning the different steps of a long and painstaking process: He rendered the eagle using the tied-motif technique, dyed the alpaca wood, set up the warp and thread the heedle on Selva’s loom, where he actually wove the poncho. While he did this, he became close to the weaver and her family. The days spent together sharing meals and recipes brought the artist into the fabric of the community.

This concern with the relational and community is by no means new for the artist, nor is his interest in the poncho and its characteristic animal images. His love of decoration and ornamentation is no secret either. Ornament is not a secondary element or merely stylistic resource; it is, as Alfred Gell argues, a technology of enchantment. The eagle poncho on Mercedes’s body is a marker of identity, but its agency is social, greater than the body of the singer herself. The performatic relationship between Mercedes and the poncho that ensues in the encounter between the body and the garment envelops the social body. “He carried pure truth wrapped in his poncho,” Jorge Cafrune once sang about Peñaloza—and that could well be said about Mercedes, whom Cafrune brought on stage for the first time in Próspero Molina plaza at the Cosquín folk festival. In so doing, he changed forever the history of Argentine folk culture and music, the conservatism that condemned bringing a woman up on stage be damned.

Like Mercedes Sosa the night she joined the folk tradition with more contemporary artistic formulations, Baggio ventures an encounter and proximity between the archaic and the contemporary. A recurring concern in his art, the politicality of craft takes the shape of a space of resistance where individual and collective memories meet to constitute a new system of forces. It was the midnight hour of history when, just a few weeks before ending a life besieged by Nazism for too long, Walter Benjamin wrote his Theses on the Philosophy of History.

Written in a state of urgency, those theses proposed an impure temporality to grapple with present threats. At stake then and now is identifying in the flash of the image of the past the possibility to launch an offensive against the violence that surrounds us, to engage that violence at the very instant when danger lurks. Although the image overpowers us, as it does in this show, we must actively do something to enable new pasts to flourish. “The past warns and assails us, but not in mechanical fashion. There has to be a willing subject,” writes Reyes Mate in Medianoche en la historia. When the few bells that still toll seem to announce that the midnight hour is once again upon us, Gabriel Baggio pricks up his ears and fixes his gaze on the jarring return of the image of the past, an image that returns from one of the stormiest periods in Argentine history that also witnessed the heights of artistic experimentation. From there he devises a new poetic-political imaginary. Perhaps the time has come for the eagle to hunt the snake.