PERSONÆ

MARTÍN SICHETTI

CURATED BY MARÍA FERNANDA PINTA

JUL 18 . — SEP 9. 2023

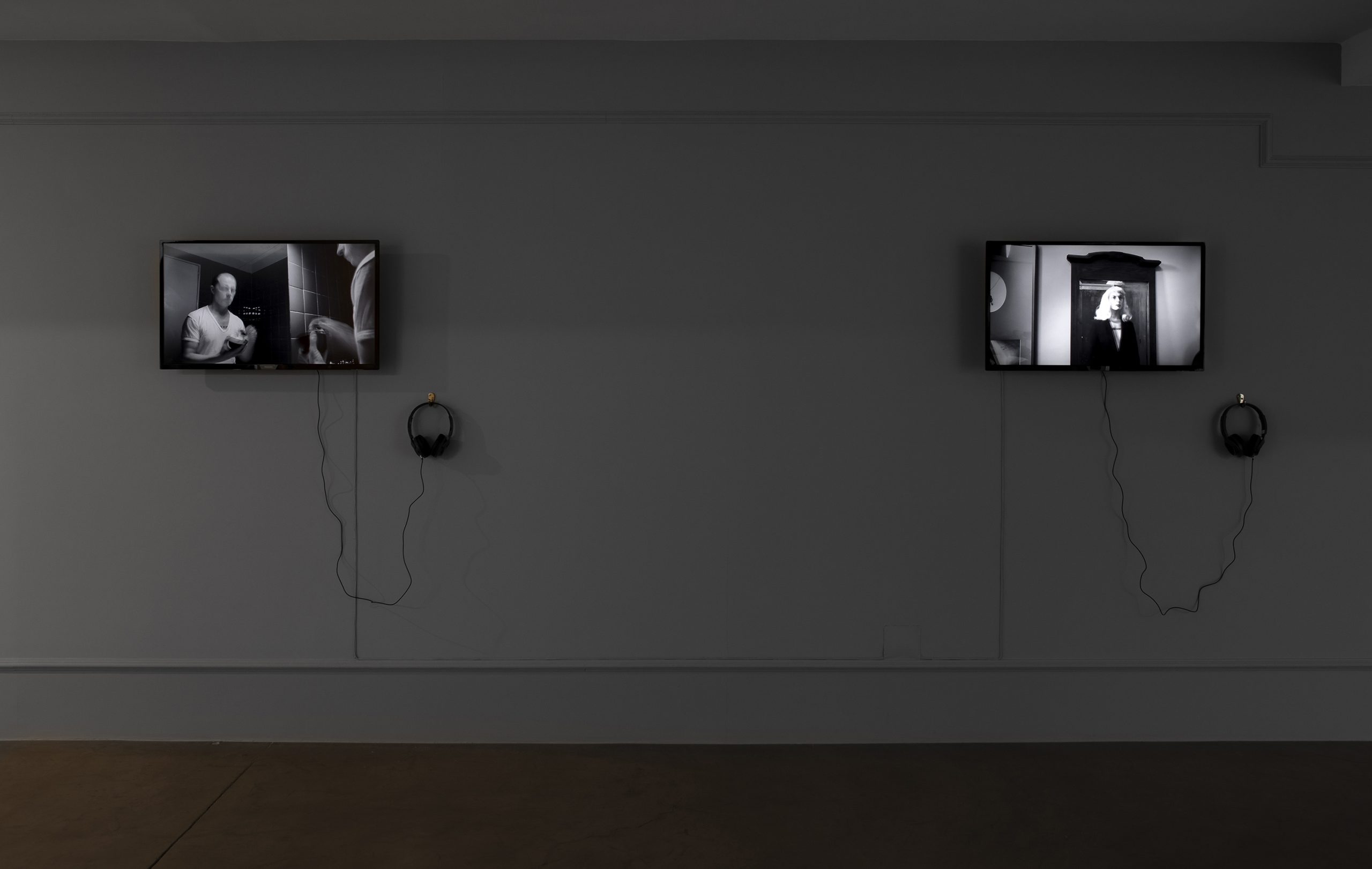

EXHIBITION VIEW

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

WORKS

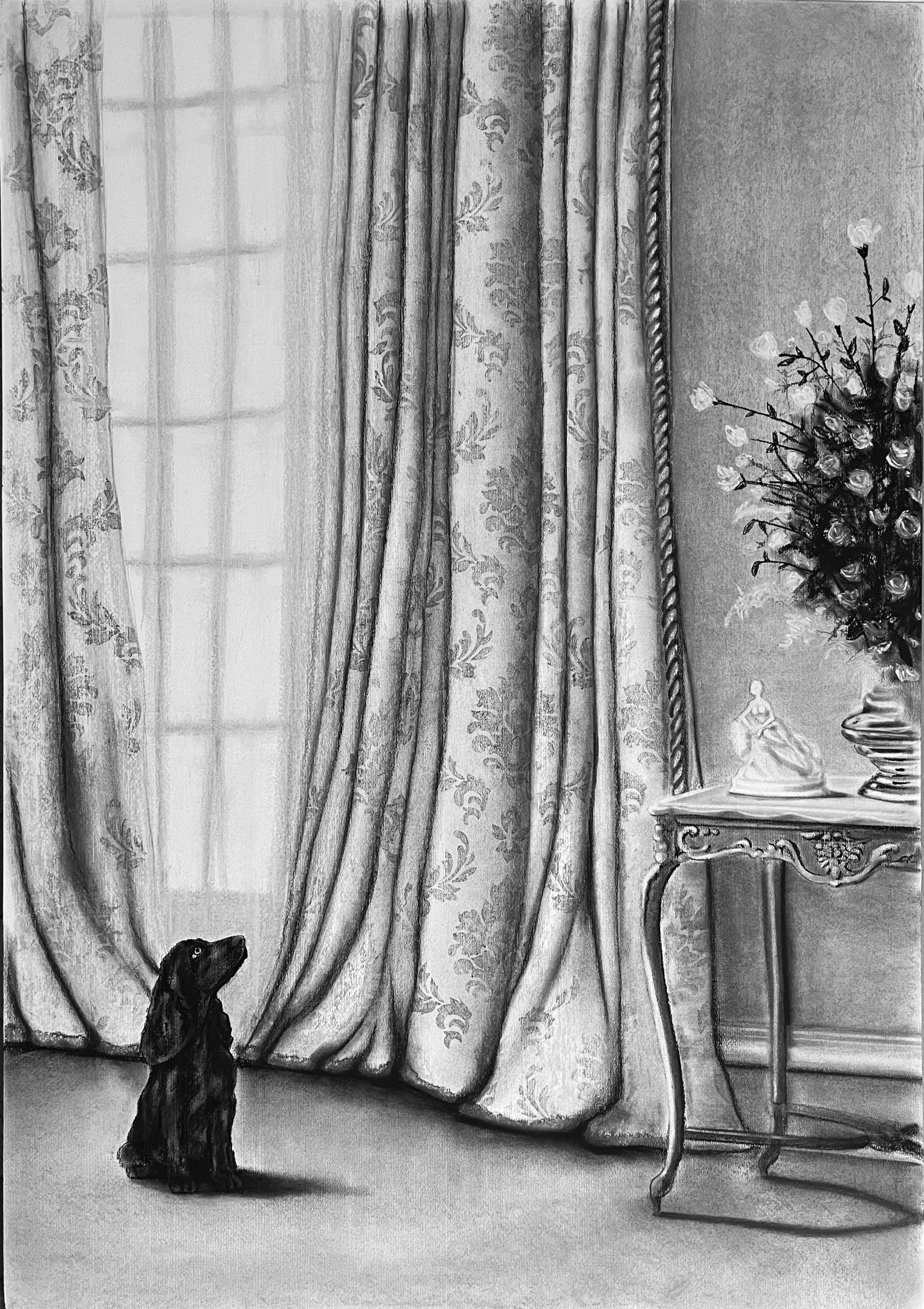

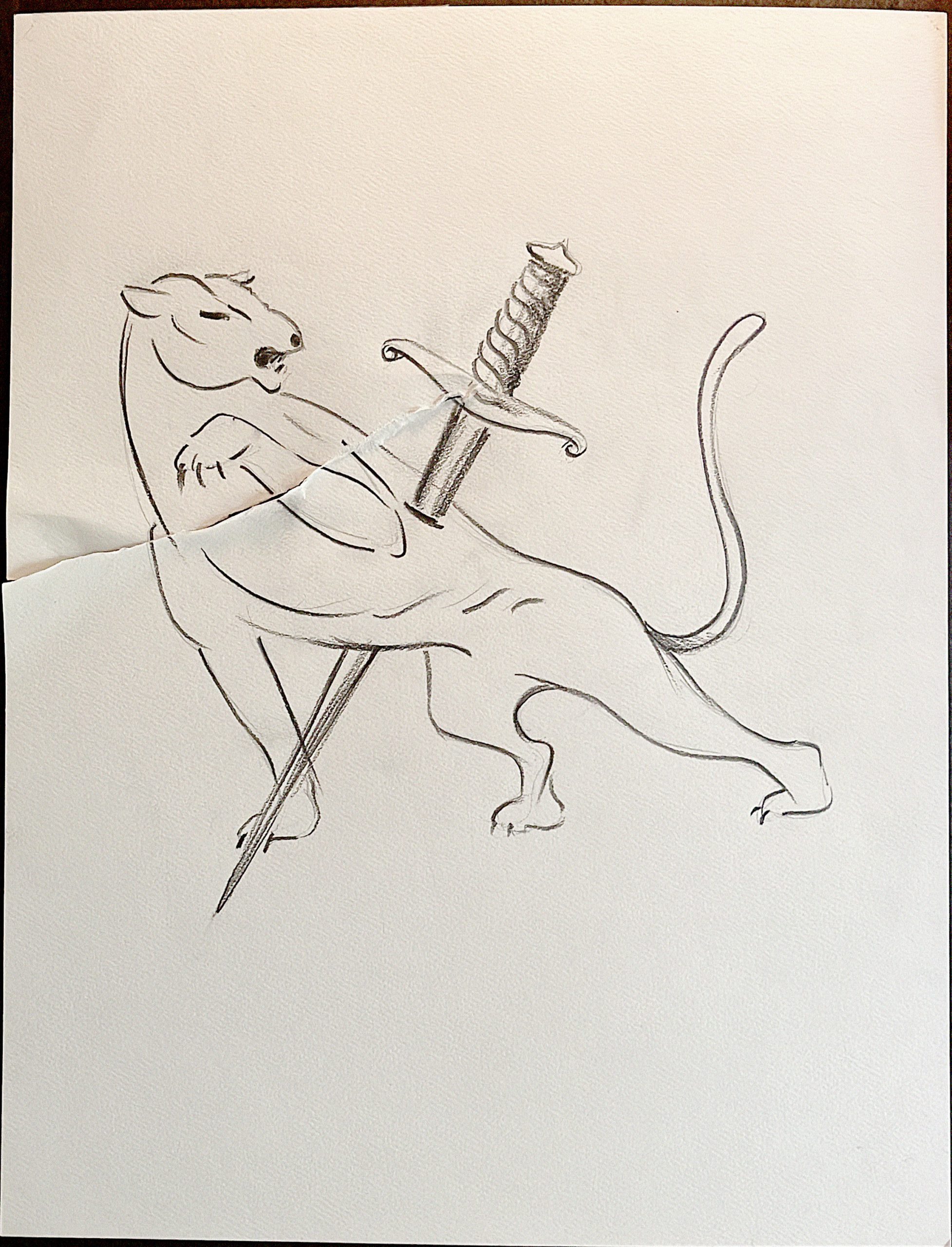

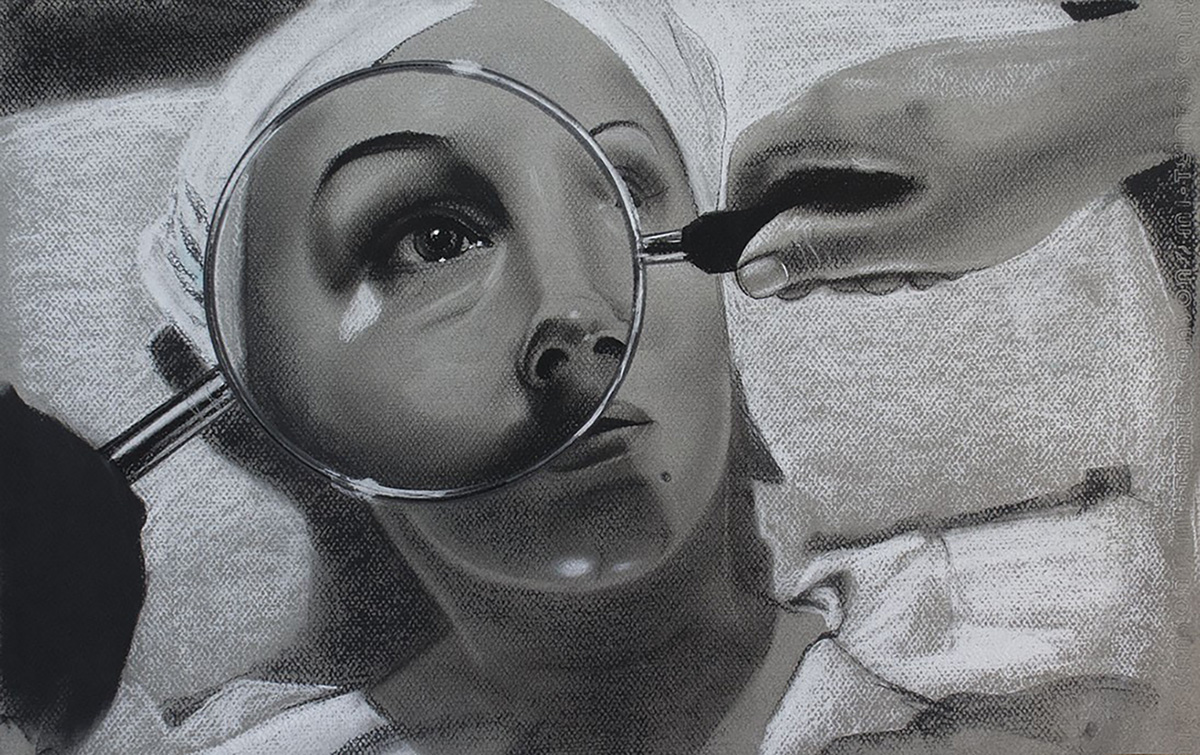

Carlotta Valdés. Series Personæ, 2021

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper

39.4 x 27.6 in

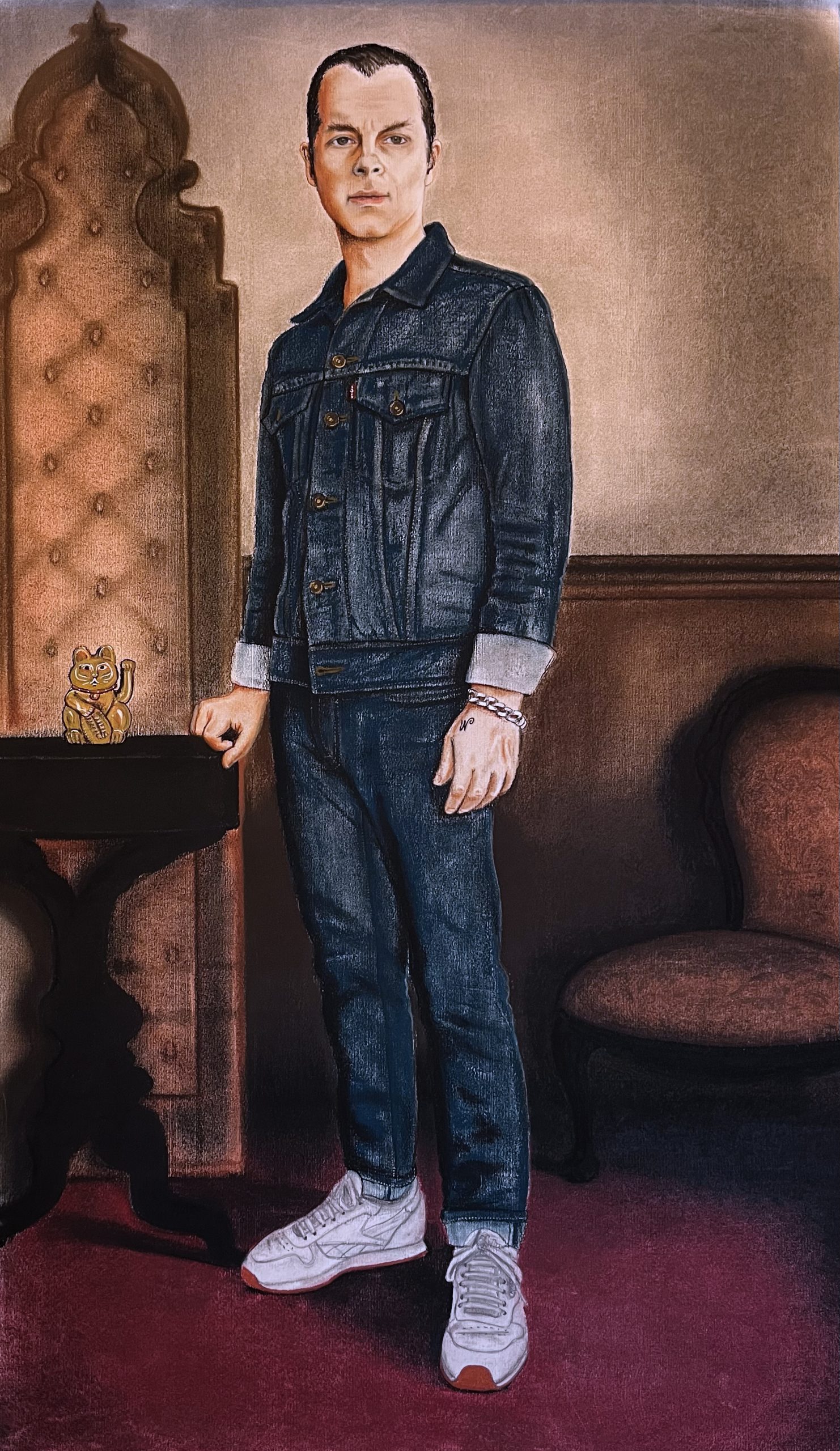

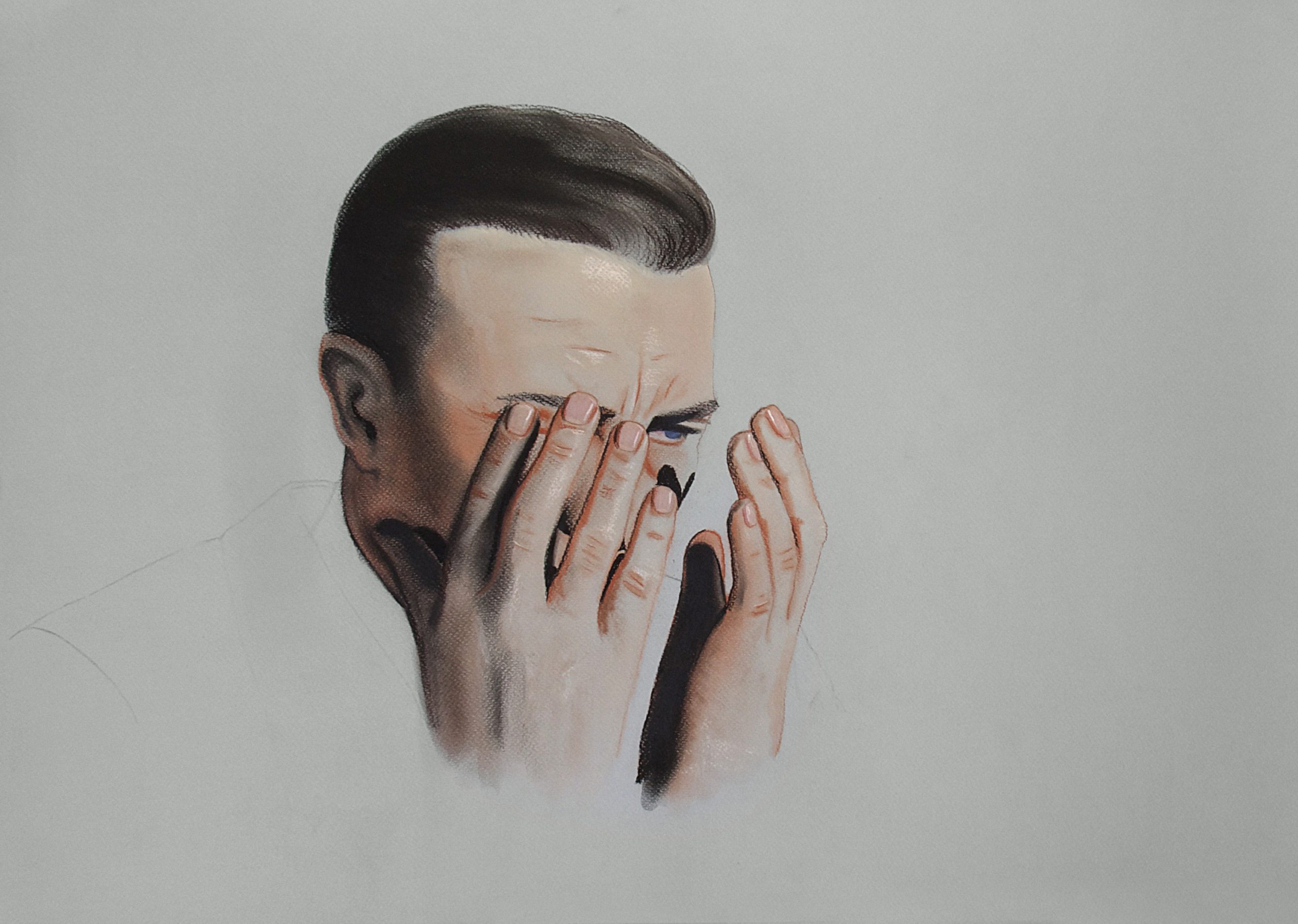

Dorian Gray. Autorretrato. Series Personæ, 2022

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper

39.4 x 23.6 in

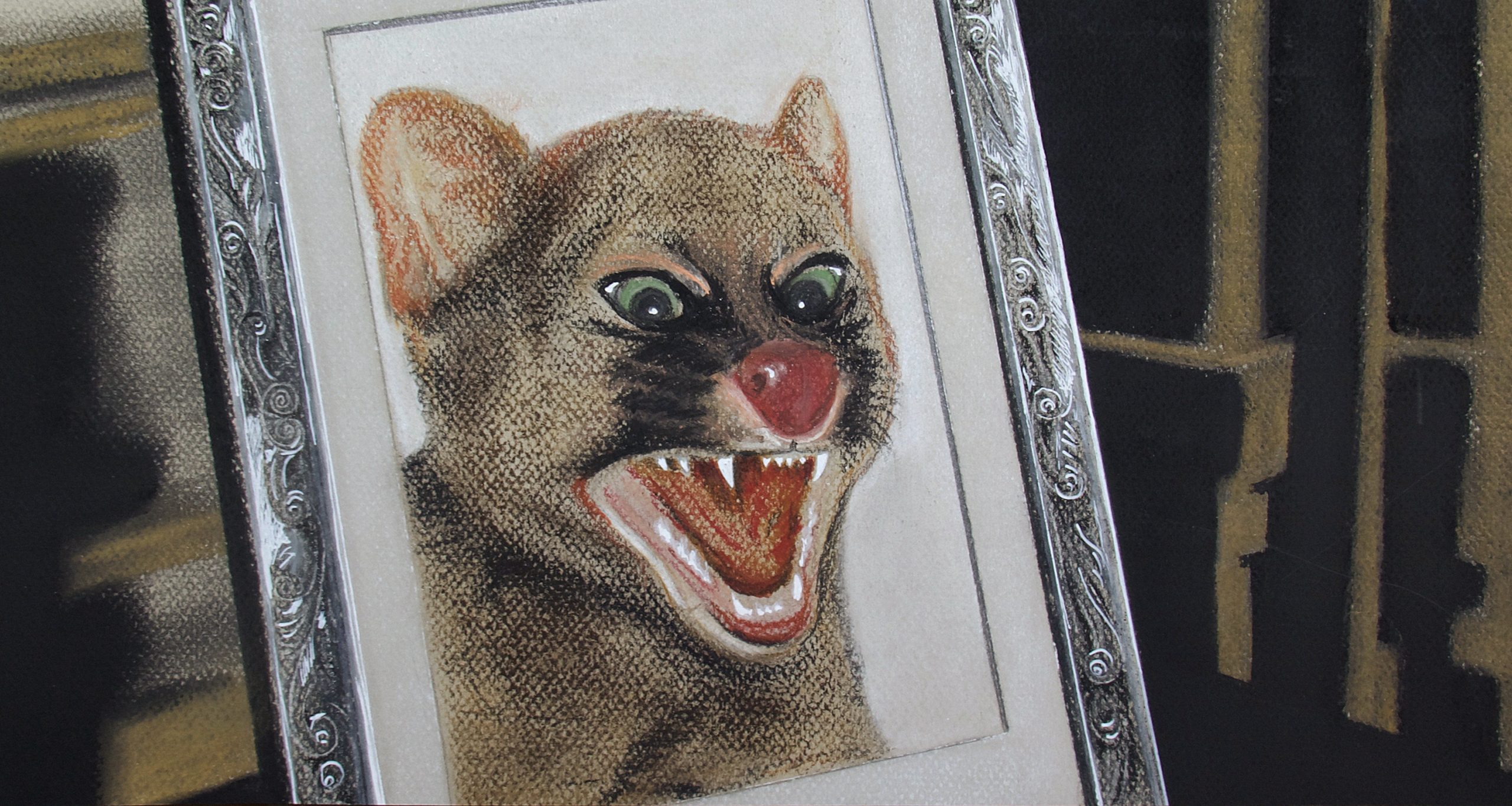

Retrato de Rebecca de Winter. Series Personæ, 2022

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper. 39.4 x 27.6 in

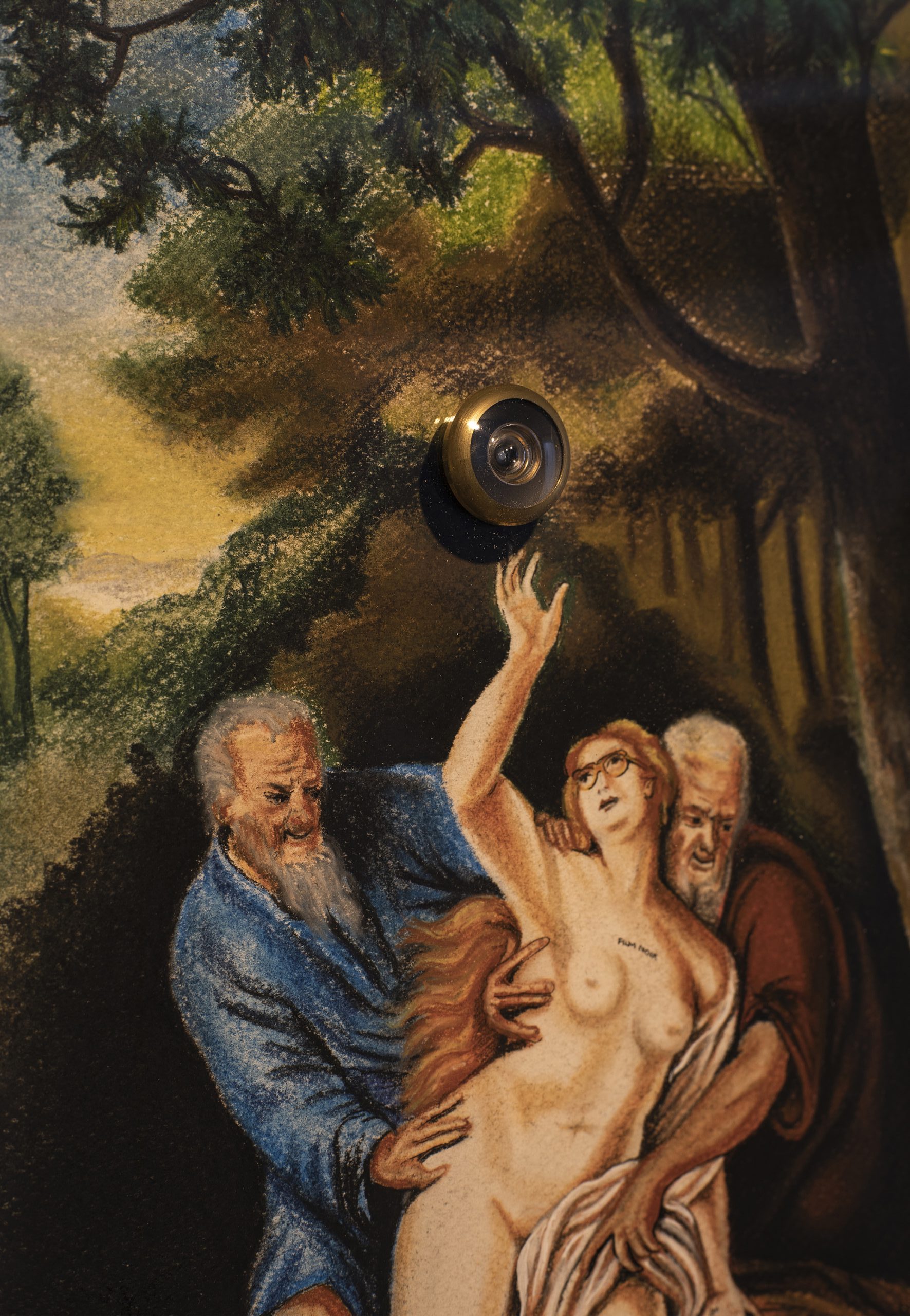

Biombo escópico. Series Personæ, 2023

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper, wooden screen with peephole

29.5 x 20.5 x 19.7 in

Retrato de su muerte. Series Personæ, 2022

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper

19.7 x 27.6 in

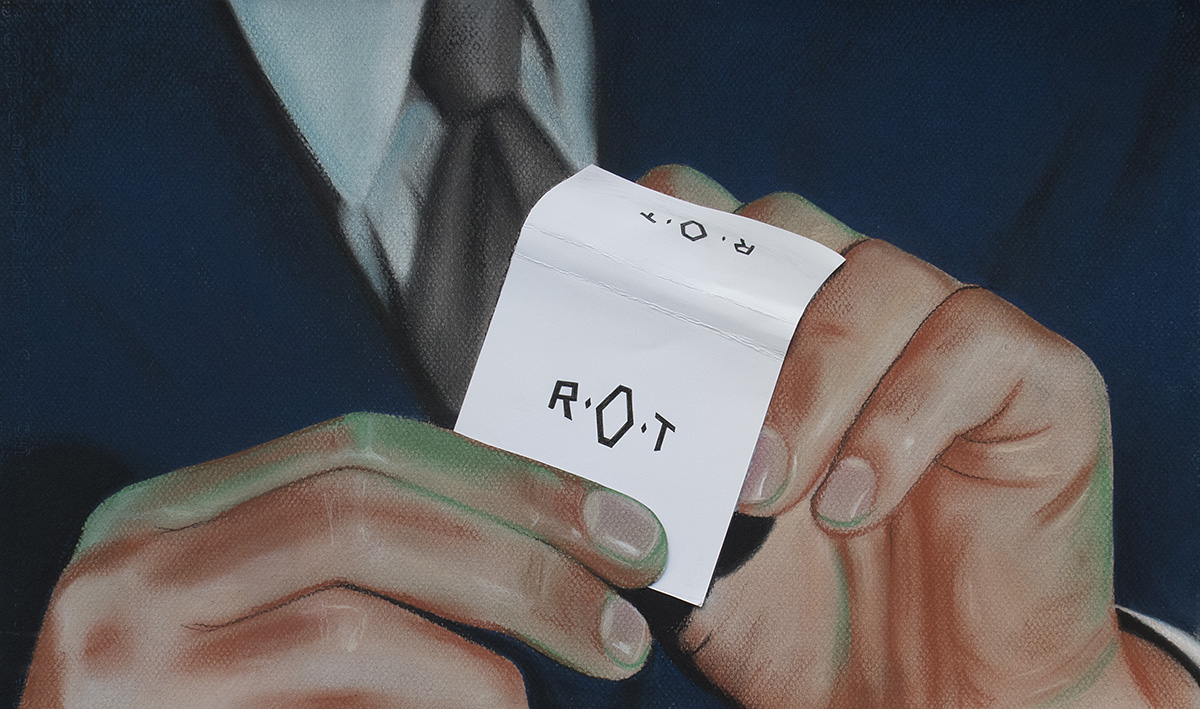

Dick Laurant is dead. Series Personæ, 2023

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper

7.9 x 19.7 in

El Replicante. Series Personæ, 2022

Martín Sichetti

Video. Duration 2’13”

Edition 1 of 3 + 2 A.P

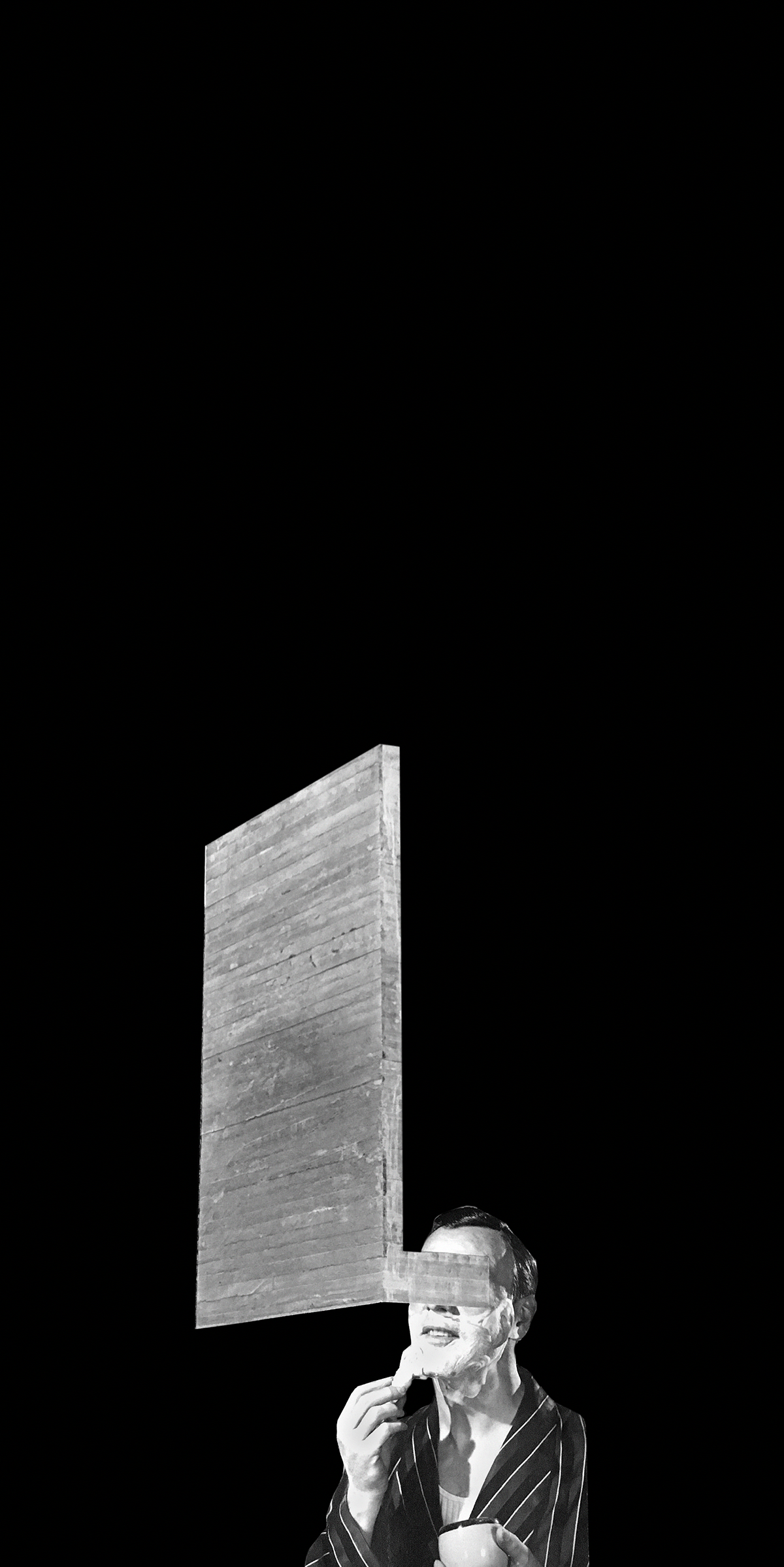

He-She Devil. Series Personæ, 2023

Martín Sichetti

Video. Duration 2’10”

3080 x 2160 px

Edition 1 of 3 + 2 A.P

Descomposición. Series Personæ, 2023

Martín Sichetti

Video. Duration 6´17”

Edition 1 of 3 + 2 A.P

Backroom

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

Backroom works

Retrato de su muerte. Series Personæ, 2023

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper

19.7 x 27.6 in

Vertigo. Series Retratos de familia, 2016

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper mounted on passepartout

31.5 x 47.2 in

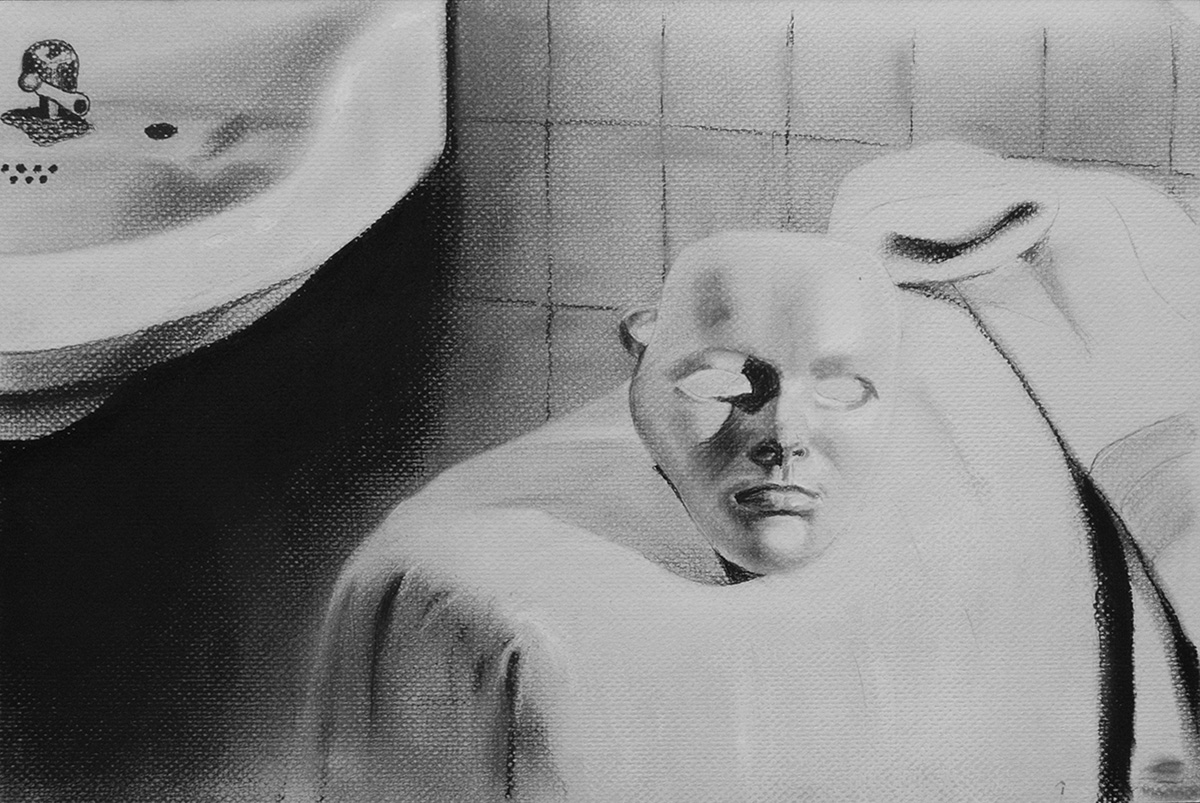

Tratamiento I. series Fatale, 2018

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper

12.4 x 19.6 in

1091 Rue La Fleur. series Fatale, 2018

Martín Sichetti

Collage, pencil, pastel, paper and velvet

12 x 15.7 in

TEXT

[…] For that is his art—to simulate absolutely, to project himself as deeply as possible into lives that are not his own. At the end of his effort his vocation becomes clear: to apply himself wholeheartedly to being nothing or to being several.

A. Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus.

I.

The Latin word persona means mask. It is derived from the Greek (in Greek theater actors wore masks to play their parts). The mask, along with other elements of the wardrobe, was what allowed the actors to project their bodies and voices out into the audience, that is, what allowed them to be seen and heard.

The relationship between actor and mask, like the one between person and character, has mutated over the course of history from differentiation to symbiosis, from contingency between person and character to rift between them. In any case, of and beyond identification, of and beyond fiction, both the person and the character are ways of appearing to others, ways of making ourselves seen and knowing ourselves to be looked at. Theater, like psychoanalysis, has taught us, first, that we act for others and, second, that masks are there, as they have always been, to make our apparitions possible.

In Personæ, Martín Sichetti tries on more than one mask but to the opposite end: He seeks to disappear. At play is being someone else, turning performance into a chance to display without being seen or to test out a sort of display that is always, and from the outset, a fleeting event anchored in ways of posing, of looking, and of performing that overtly construct a character, a persona, or a role through more or less identifiable repertoires and conventions. Regardless of vraisemblance and imposture—or perhaps because of them—he seeks to turn performance into the locus of drama and all its vehement outgrowths.

Thus, he performs for others as long as the viewers play the game, that is, as long as they recognize the masks from the personal history of film Martín has constructed over the course of his production, and understand themselves to be voyeurs.

And, regardless, to look and perform—to try those actions out—as radically others, like those animals that pop up here and there in Personæ.

II.

In this third exhibition at Hache, Martín once again looks to a universe of film that includes directors like Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch, genres like fantasy, horror, science fiction, and thrillers, and styles like film noir. Drawings, collages, videos, and performances created from the learned vision of a film lover interrogate the gestures, objects, details, and atmospheres that, when caught in stills, turn into emblems of the pathos that drives characters, conflicts, and passions on and off the movie screen. Drawing on those sources, Martín constructs a poetics of his own. In it, the dreamlike, the mysterious, the scopic drive, and the fetish reign supreme, though that does not mean there is no humor or disbelief when he appropriates images steep in the glamour and cliché characteristic of show-business culture. What unsettles, but also allures, is that very tension between a world that knows itself to be performance and staging and another that whispers things we can barely understand even though they are not entirely unknown to us.

Furthering previous explorations and embarking on new ones, Martín’s work revolves around three axes. First, the portrait. If in earlier work he engaged in careful impersonation of figures like Marilyn Monroe or played the part of characters from the films that make up his universe—think of his videos Rowena (2018) and Darling Pet Monkey (2011)—here he takes the place of Dorian Gray as read in the 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray or of Carlotta as embodied by Midge, Scottie’s abiding friend in Vertigo (1957). The artist is in the body and scene of the other.

Second, he explores an animal world that strives for a place in the scene. Animals have always been there—Martin has worked with films like The Birds (1963) and Psycho (1960)—as symbols of natural or supernatural forces, as the beings that live within humans who no do not really know themselves, or as his characters’ companions. In any case, his research on animals’ vision of us and our vision of them takes the form of a question rather than an answer.

Third, these works—like others by our artist—take the shape of specific quotes drawn from a wide corpus of films, but here references are crossed between films. Consider the video HeShe Devil, a strange hybrid of She Devil (1957), Lost Highway (1997) and Twin Peaks (2017). Connecting motifs and themes, but also styles and moments from film history, these works are the inevitable point of departure of a narrative that goes beyond and turns out to be something else.

At play in Personæ are many ways of being—and not being—of inhabiting worlds, and of exchanging glances.

María Fernanda Pinta