Maldito duende

DANI UMPI

curaTED BY Gachi Hasper

EXHIBITION DESIGN Osías Yanov

aUG 8. — sep 16. 2017

EXHIBITION VIEW

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

WORKS

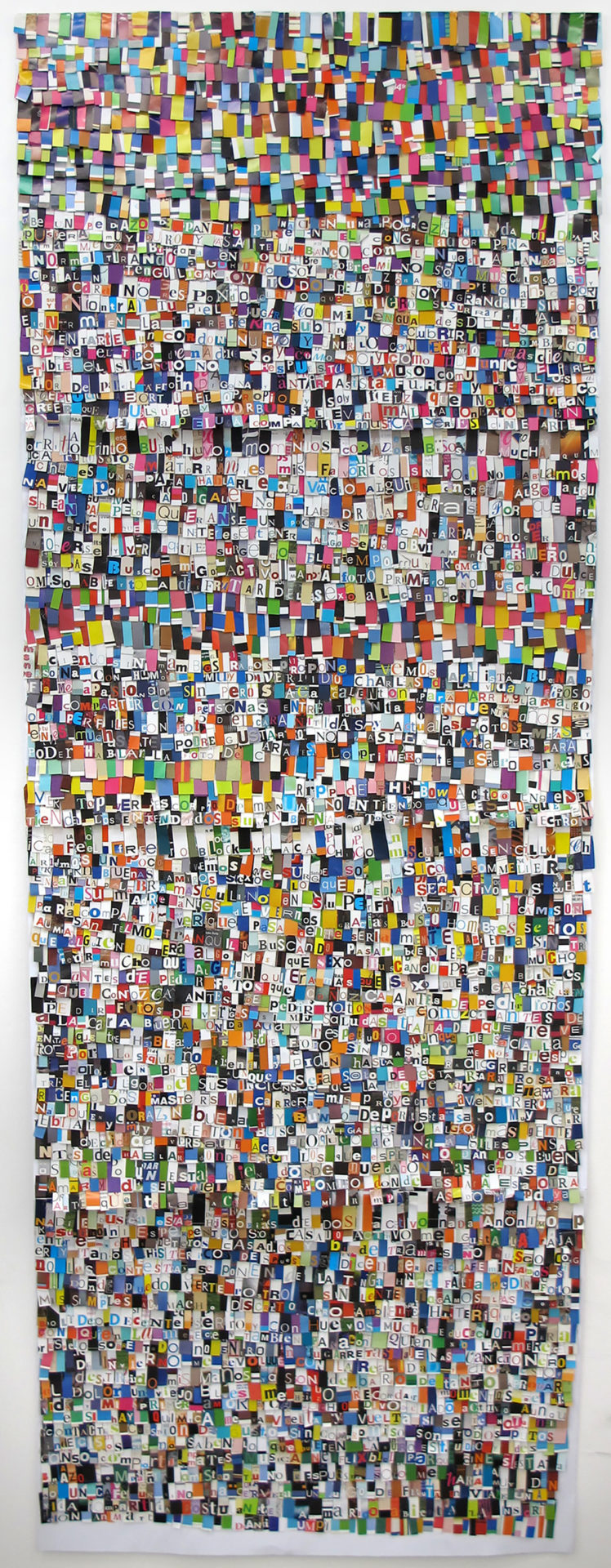

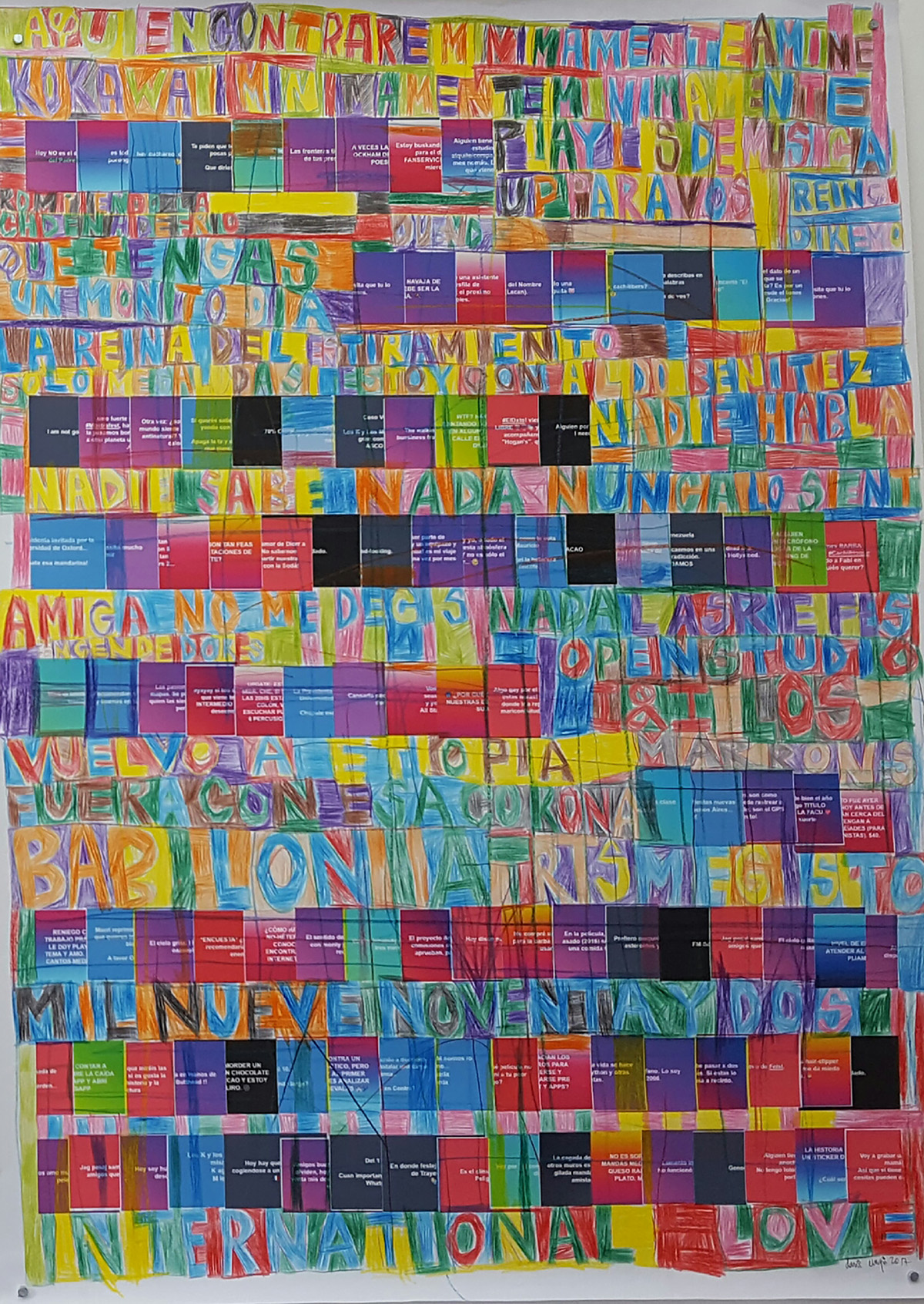

Aquí encontraré mínimamente animé, 2017

Dani Umpi

Facebook screenshots and pencil on paper

38.5 x 26.7 in

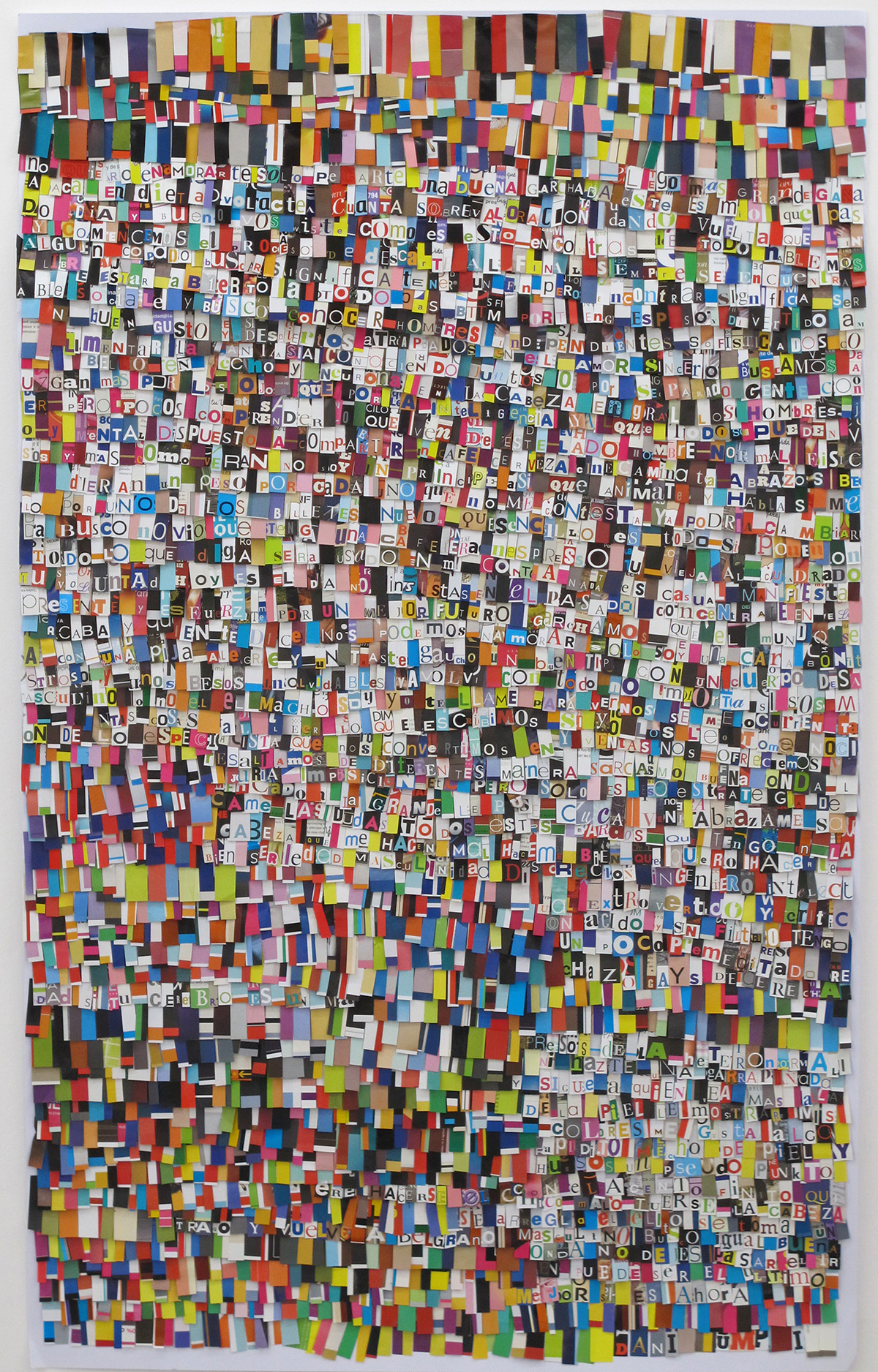

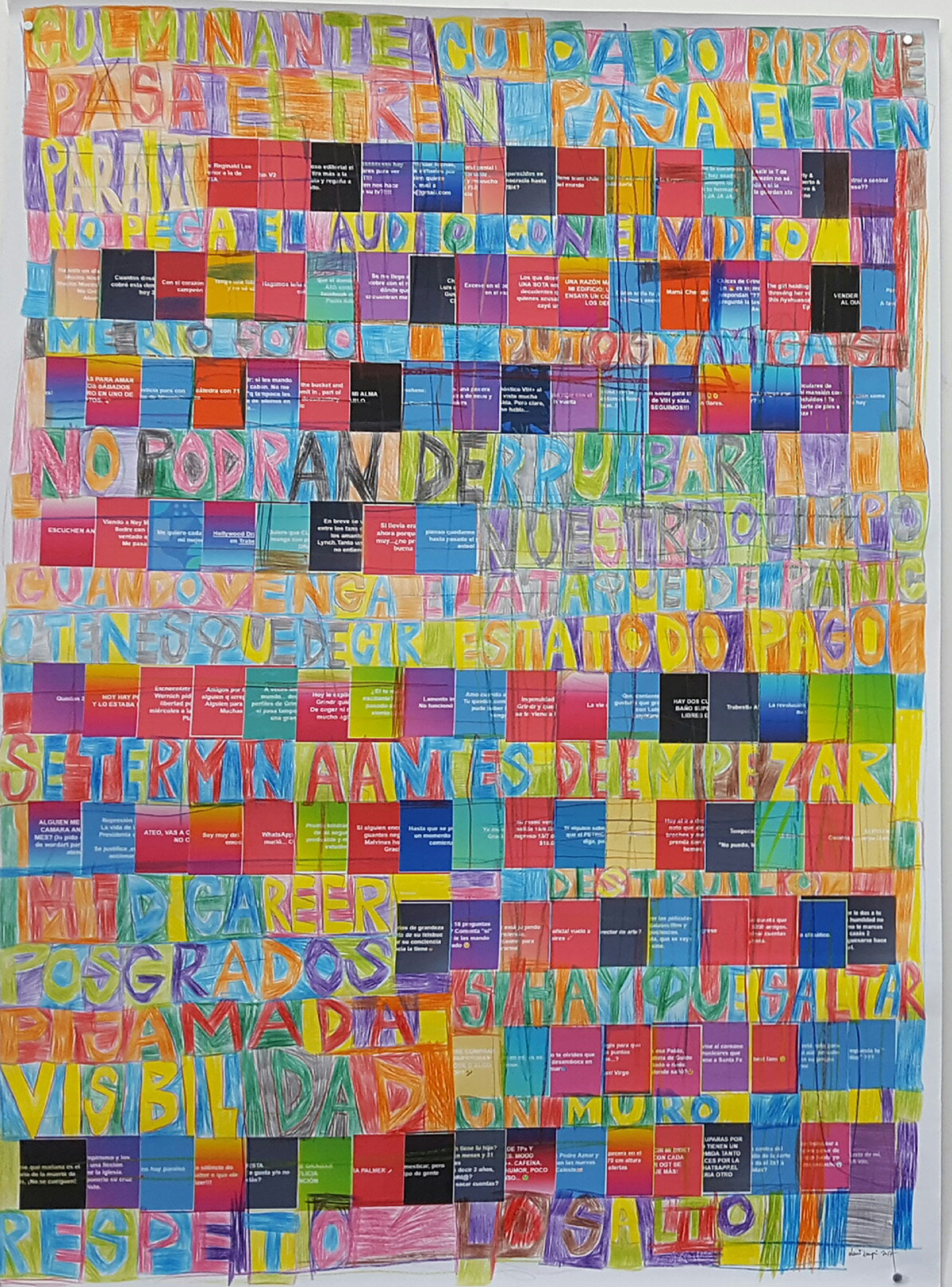

Culminante cuidado porque pasa el tren, 2017

Dani Umpi

Facebook screenshots and pencil on paper

38.5 x 26.7 in

TEXT

Does Dani Umpi need a text?

Dani Umpi explained to me that this show is called Maldito Duende [Damned Elf] “for a song by the Héroes del Silencio that I liked a lot when I was a kid. In the 2000s, Raphael did a sublime cover of it (the producer was Carlos Jean). At the end there is this really druggy phrase that goes ‘you feel so strong you don’t think anyone can lay a finger on you.’ That is the essence of the elf: being invincible, devastating, beholden to no one.”

Umpi is a surrealist cannibal: dismemberment, rewriting, extreme freedom. He crosses all the limits—from performance to song, from visual collage to novel—without compromising autonomies. He deals in texts in different supports. But the lyrics to the song Maldito Duende are nowhere to be found in the works in this show—and the absent reference is enticing.

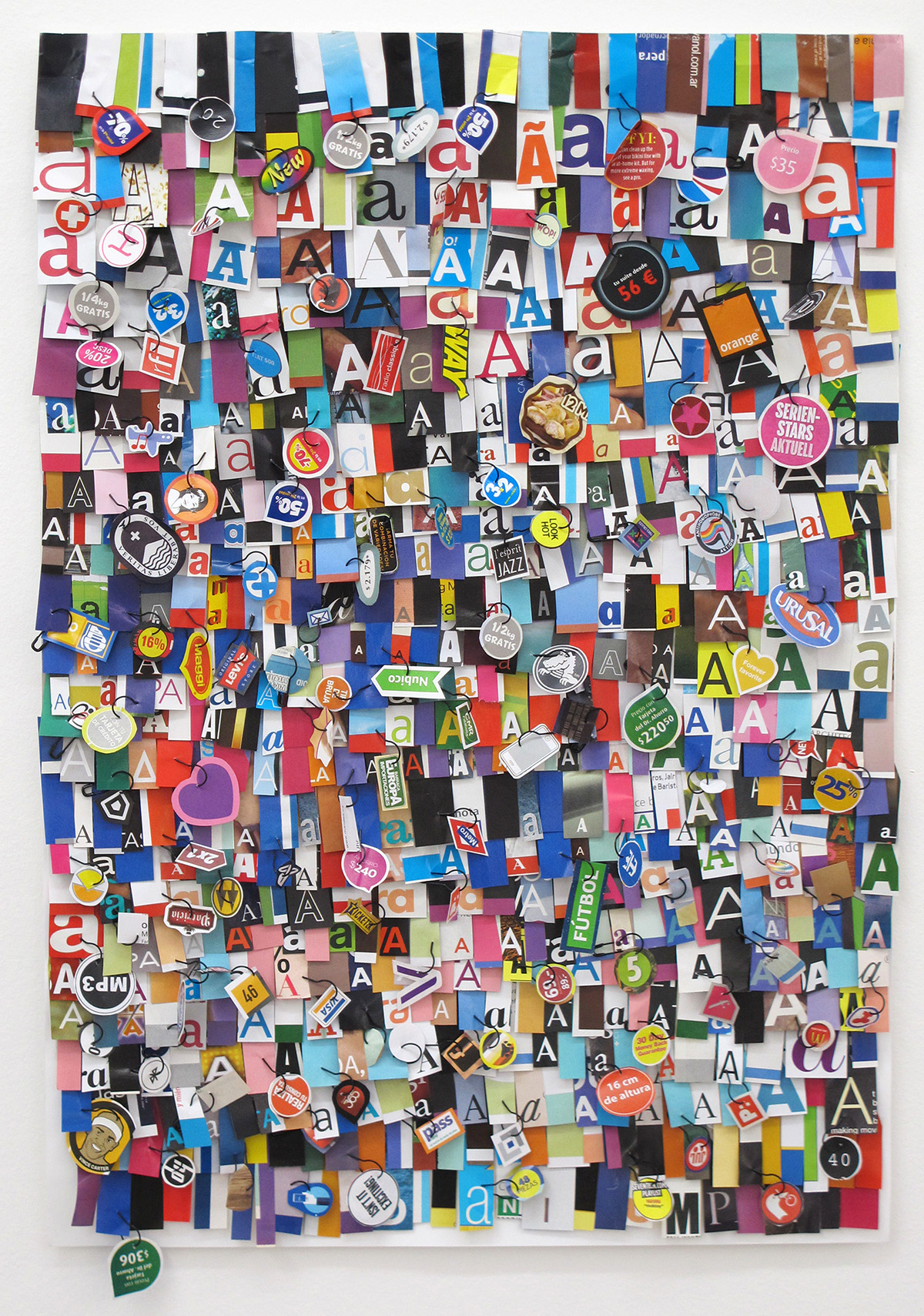

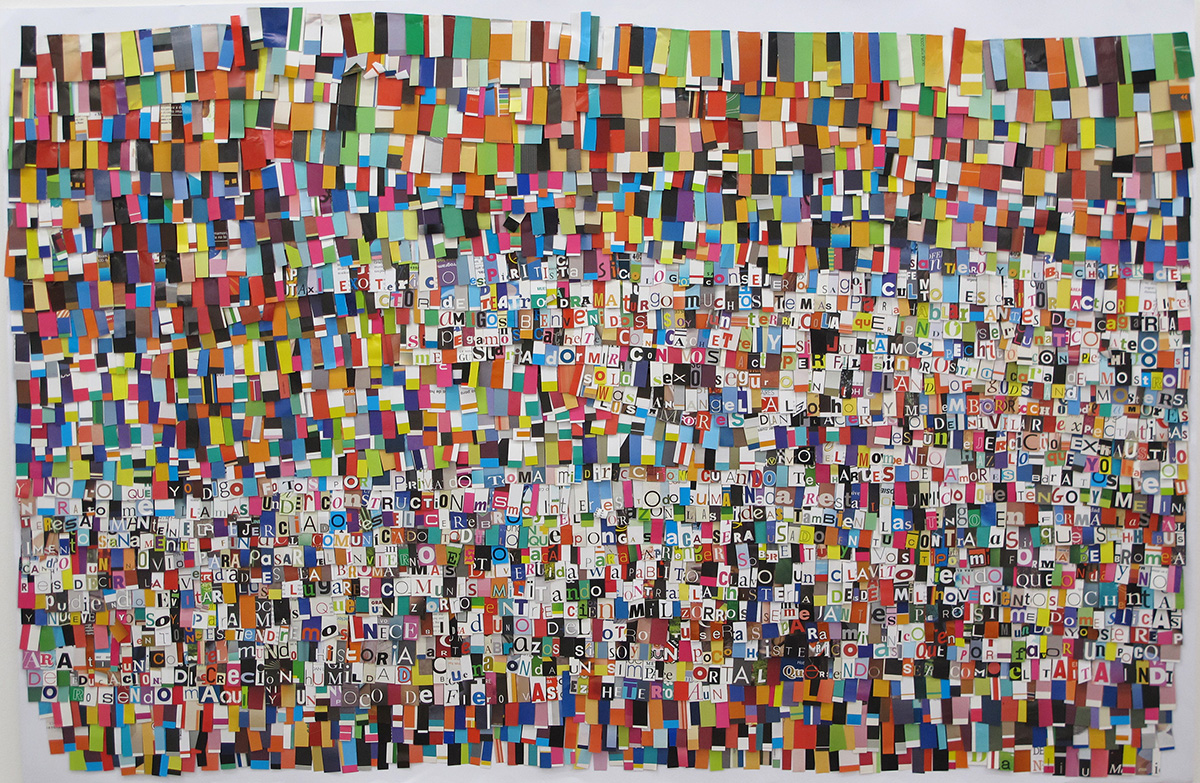

Should one go slowly, observing and reading each of his collages or, rather, take his work in as a whole with a sweeping overview? I think of the lonely—scholastic, feminine—work of leafing through magazines, of cutting them to bits, removing the letters and the solids beneath them; clipping the photo portraits of the columnists, and dozens of other faces. I am interested in the moment that follows, when he navigates that endless, dismembered graphic material, and finds different pieces to be regrouped, joined, arranged, sewn, glued, without cutting the fringe . . . I remember Enrique Ahriman and the endless patience of putting together the puzzle of a great painting, and—in a way—the idea that any visual form is like a text that can be manipulated, projected, shared.

Work based on middle-class shopping magazines, television, and the Internet in all likelihood partakes of Pop Art, as does confronting consumer culture and high culture and the use of the repeated sign as resource. The choice of a campaesthetic also means the choice of LGTB queer folklore: idols, meeting grounds, expressions, passions.

*

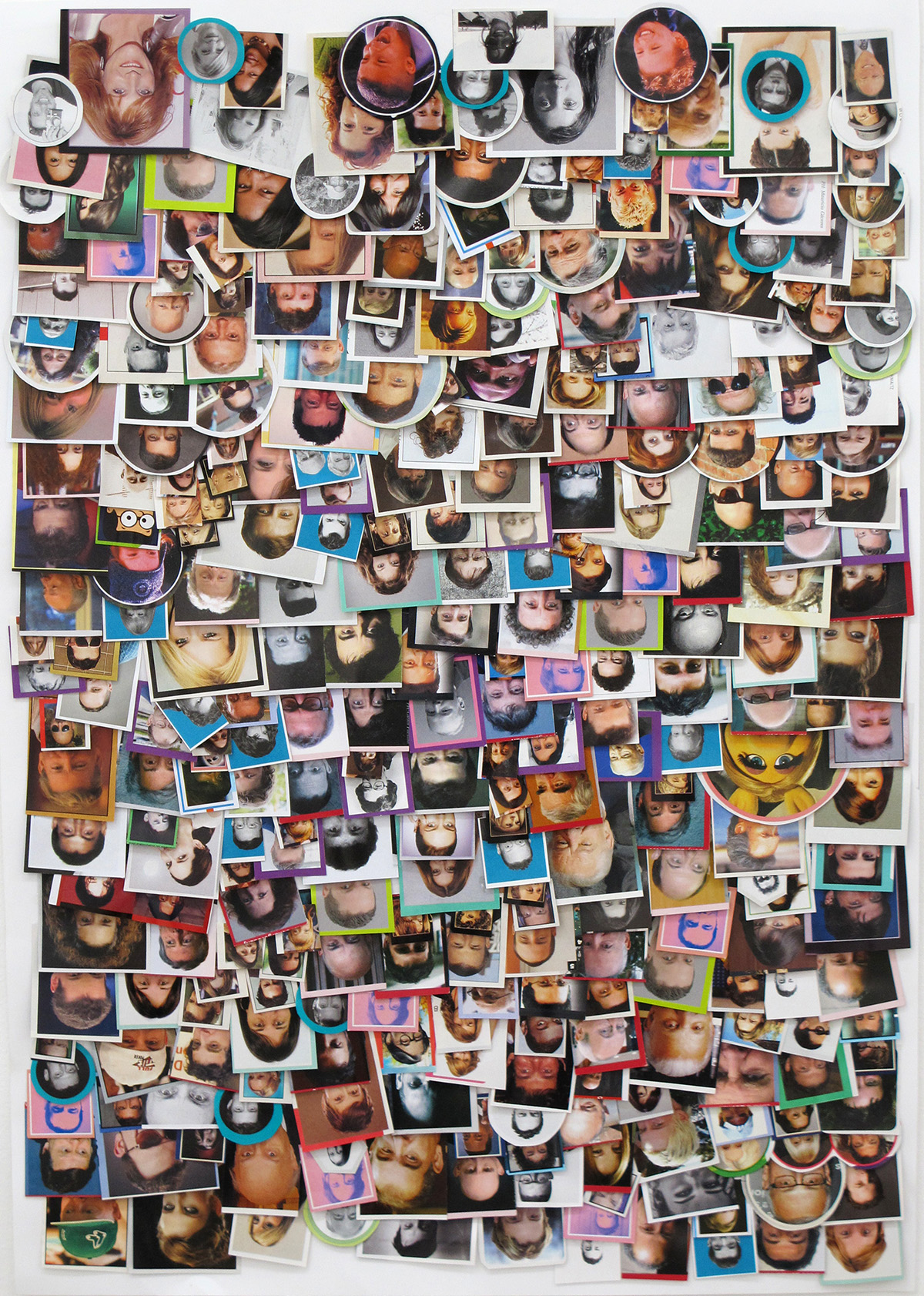

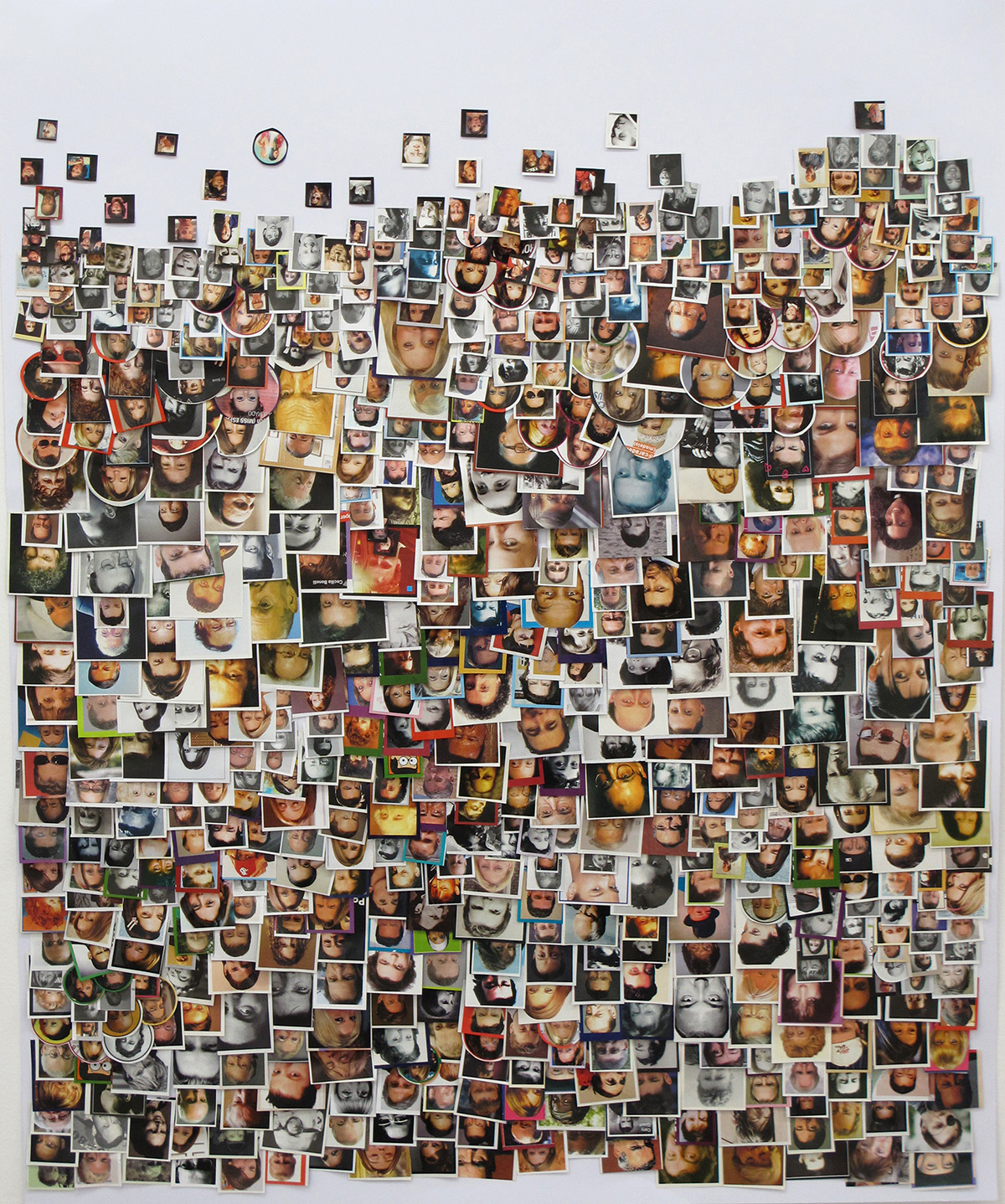

Caras [Faces]: Hundred of ID-like photos layered so that one photo covers the mouth of the person in the next; just the little eyes staring out at us upside down.

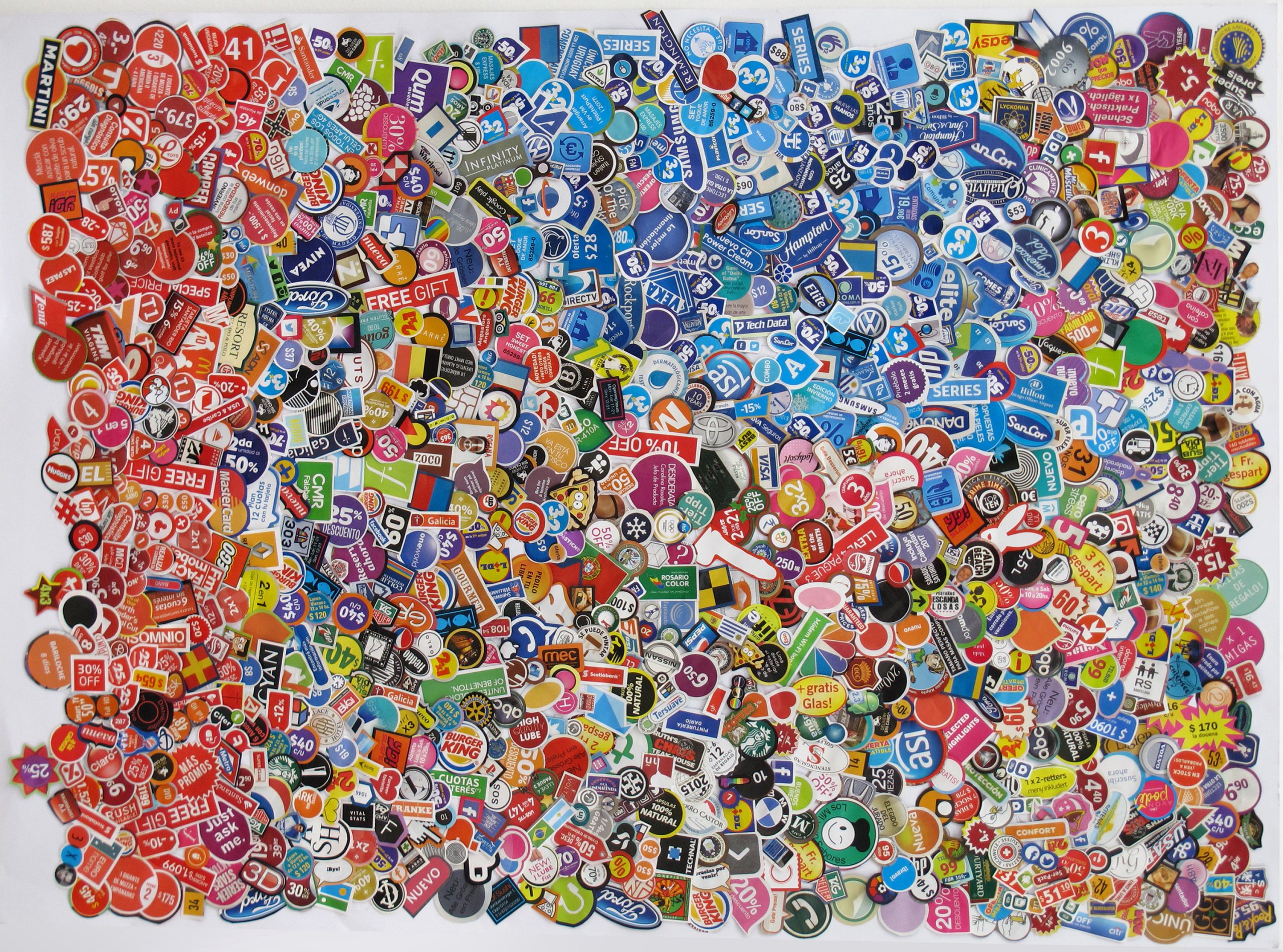

Duendelatría 1, 2 y 3 [Elfolatry 1, 2, and 3]: Little circles, shields, price tags, banners, stars, glittery shapes, logos, labels, brands. A whimsical heap of forms and colors that attests to obsessiveness.

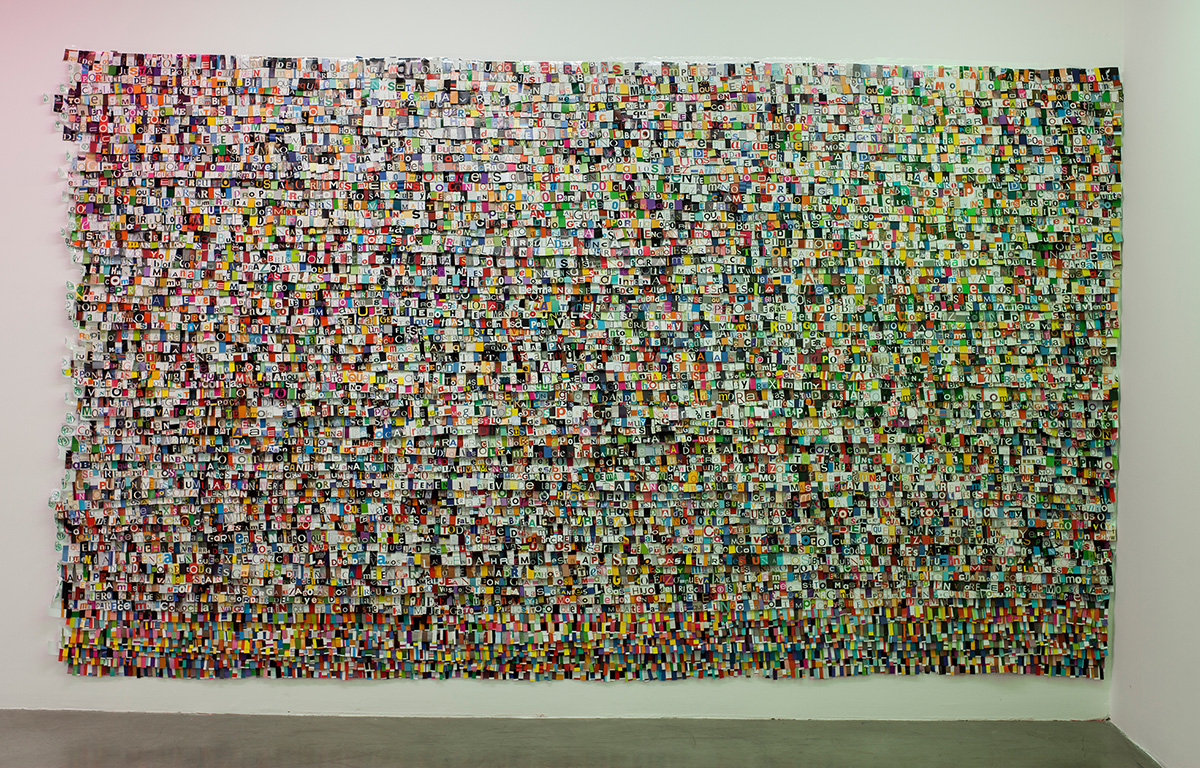

Grinder Agosto [Grinder August]; Grinder Julio [Grinder July]: Texts from screen shots of the app where fags hook up. Manuela Trasobares: a speech given by the Spanish anarchist transsexual opera singer on Catalan television in the nineties. The literary-visual collage requires that the viewer formulate a complex reading.

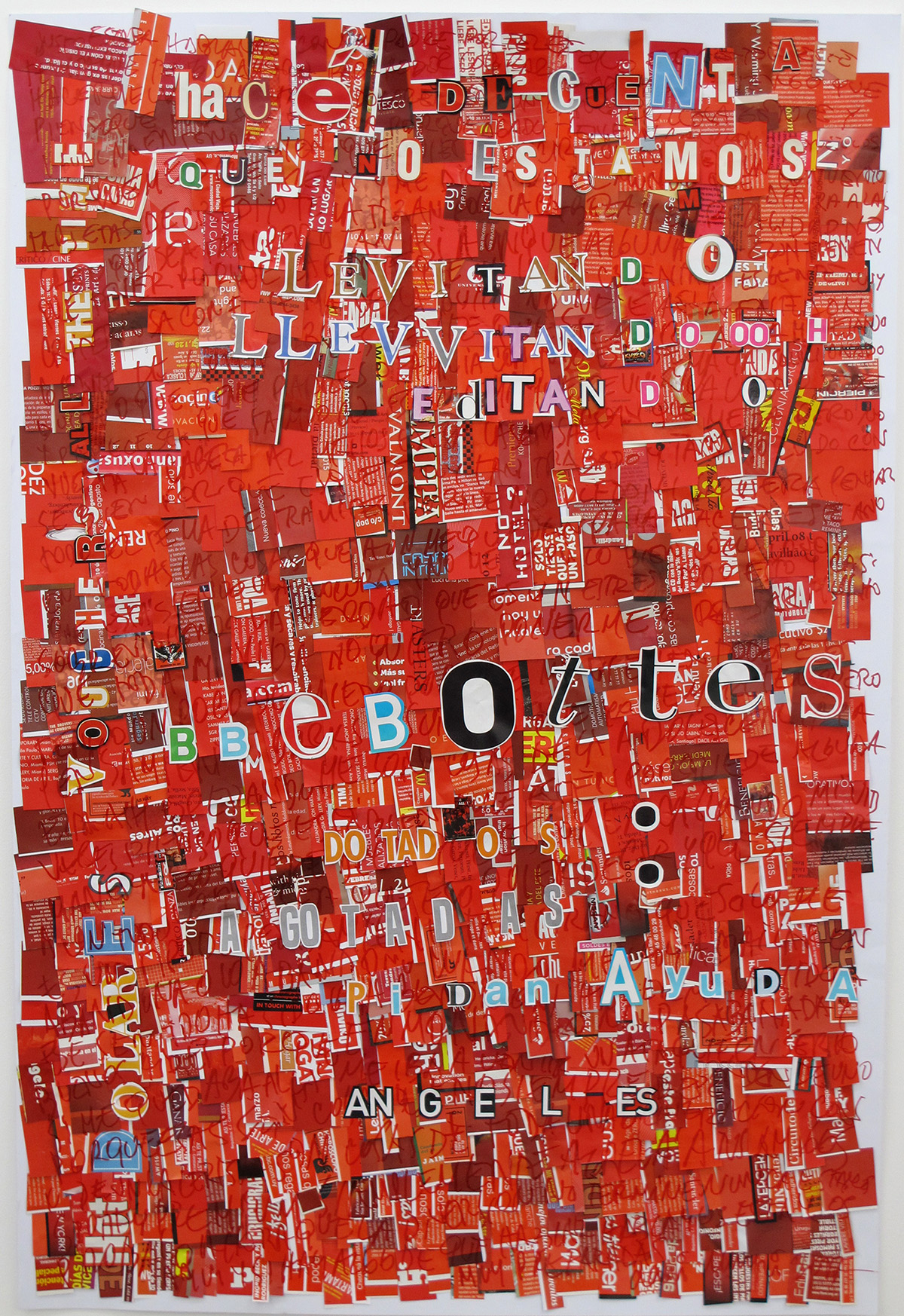

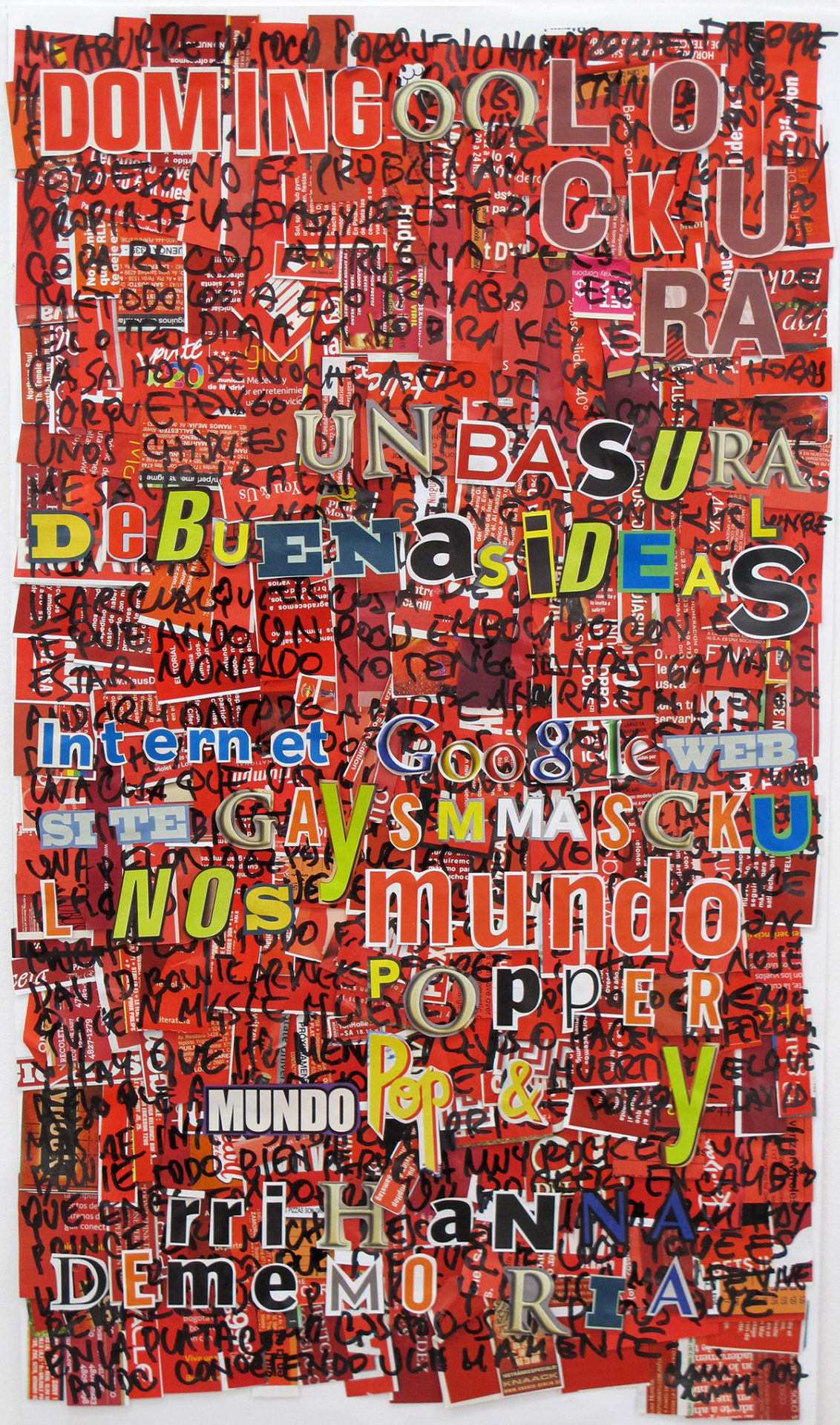

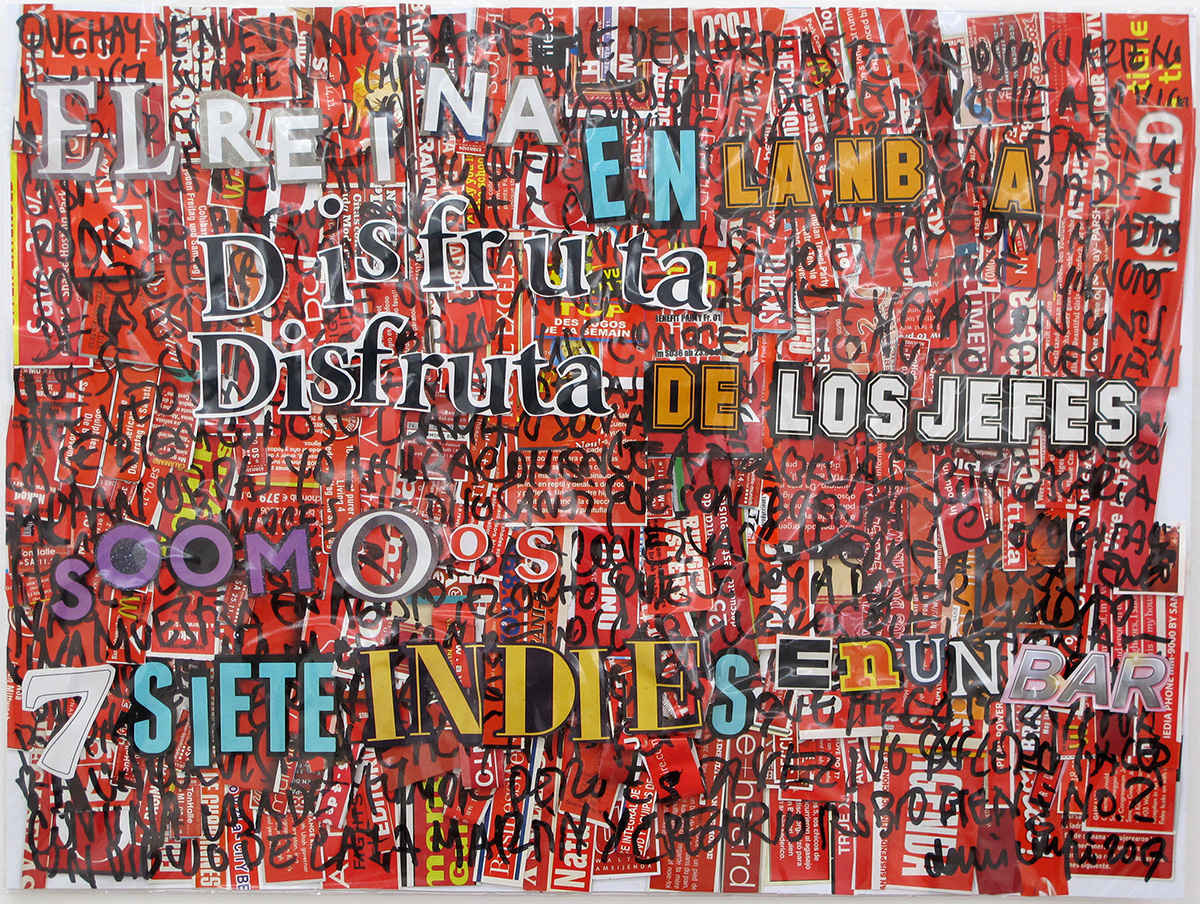

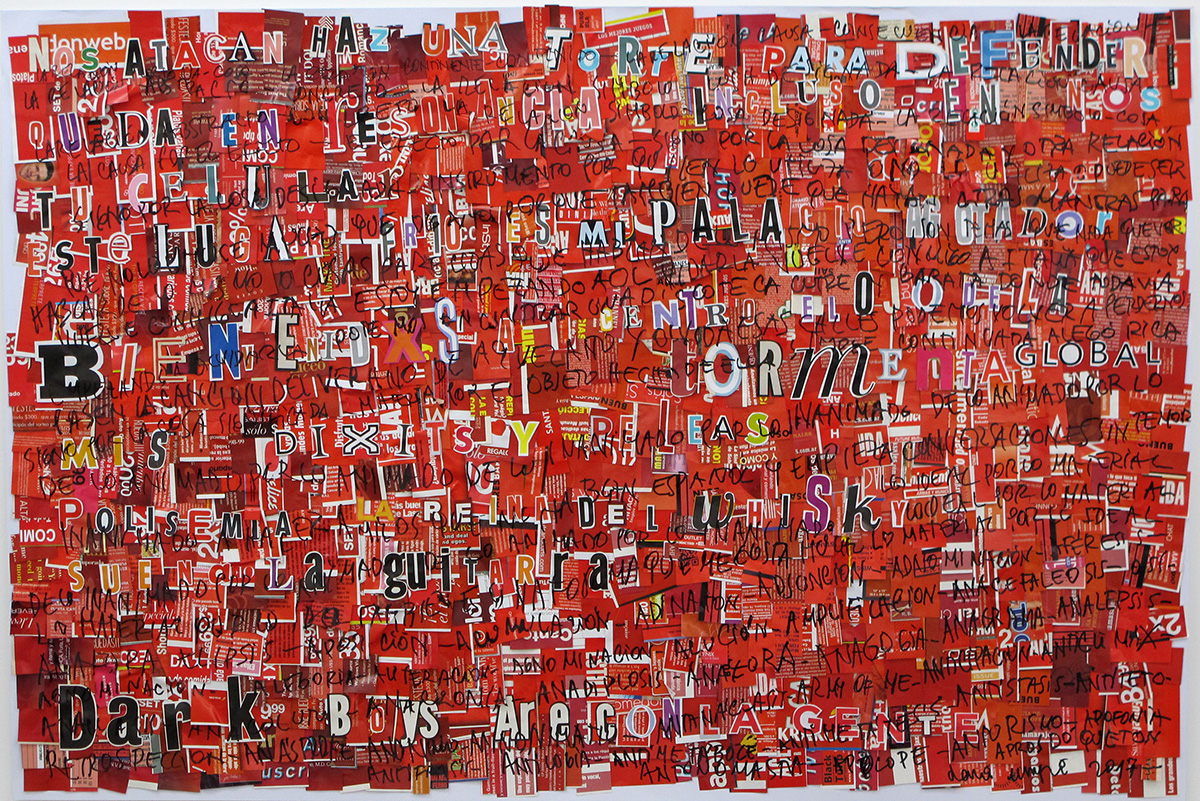

The texts in Domingo Lockura [Sunday Lockura], Bbebottes, Nos Atacan [We are under Attack], and La Reina de la NBA [The Queen of the NBA] are produced two ways: a collage of letters or letters written with marker. In both cases, the phrases—unlike the media or political texts in his work—are fairly disjointed and hard to read. He writes random texts on a paper in Coca-Cola red or, in a reverse operation, uses letters cut out from that red paper and then rewritten with marker.

*

Over ten years ago, in the Viejo Hotel in the coastal town of Ostende, Dani Umpi set out to rewrite Where There’s Love There’s Hate, the novel by Silvina Ocampo and Bioy Casares. Umpi’s rewriting is reminiscent of the hand “scans” of worshipers who sweep their hands over the Old Testament as they read it. Essential to the act of reading is doing it out loud and guiding it by brushing your fingers over the words. Letters and their shapes have magical power.

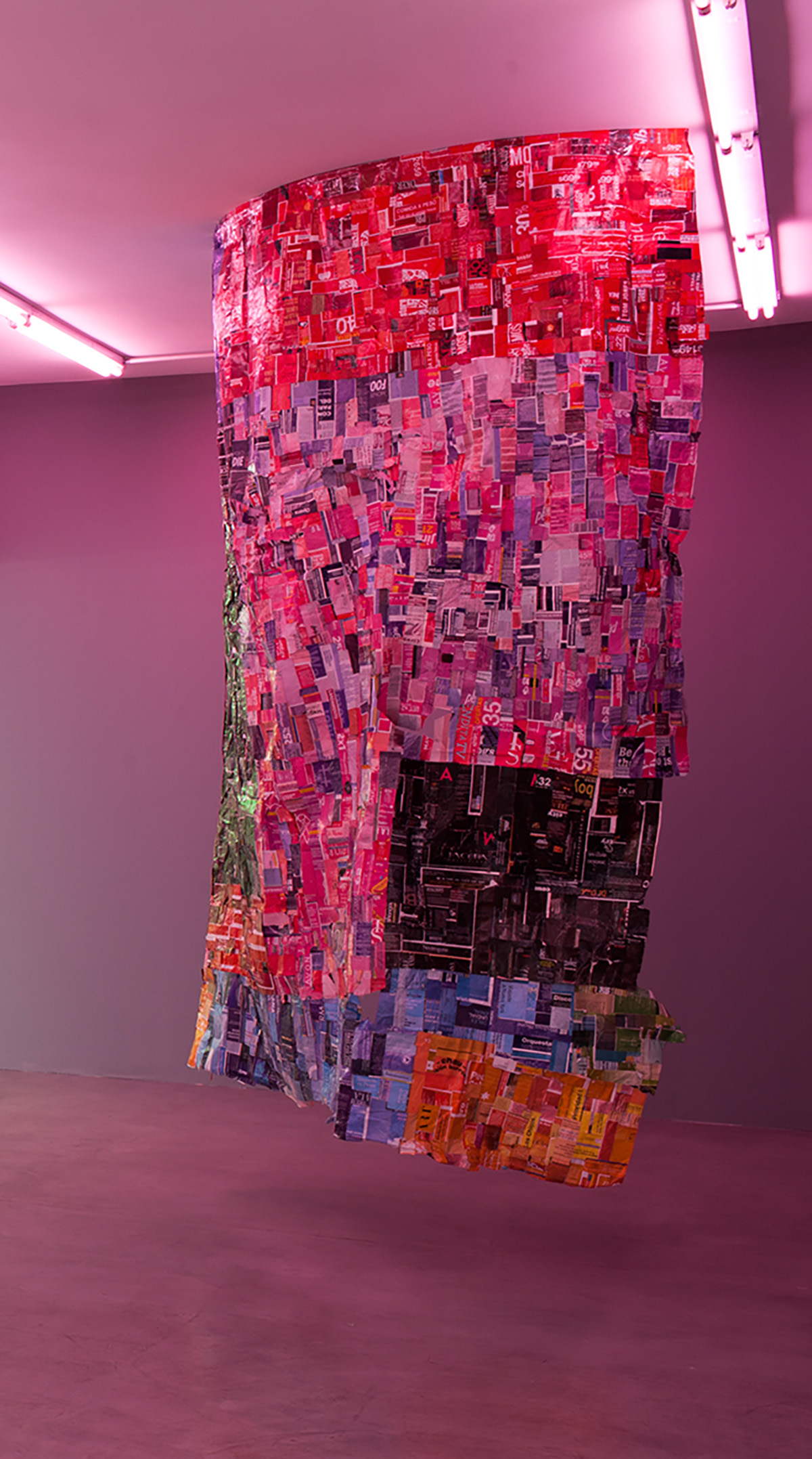

He is so gentle and modest off stage, but so amazingly diva-like when, wig on head, he sings swinging his parangolé—a sort of collage of paper stiffened with packing tape to yield a fabric that is both cape and poncho. Umpi’s parangolés are unbelievably trashy, yet glamorous and bright.

One parangolé tradition looks back to Helio Oiticica and his sense of freedom in daily life, as total work that must act outside the restricted circuit of learned culture. It is believed that in Oiticica’s first drawing of a parangolé (1964), the object was a wig, a parangolé for the head. The parangolé not only has to dress and cover the body, but also to move, to be dance, to be samba. Umpi embraces the power of that cross-dressing in dancing work in an array of public spaces.

Now, Dani Umpi invites us to interact with parangolés hanging from the ceiling in an art gallery, a proposal that requires active viewers. The “avant-garde” is what has already happened; what matters is to do it again.

Gachi Hasper

artists

DANI UMPI