La vida

FLORENCIA BÖHTLINGK

curated by Alejo Ponce de León

Mar 13. — apr 21. 2018

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

works

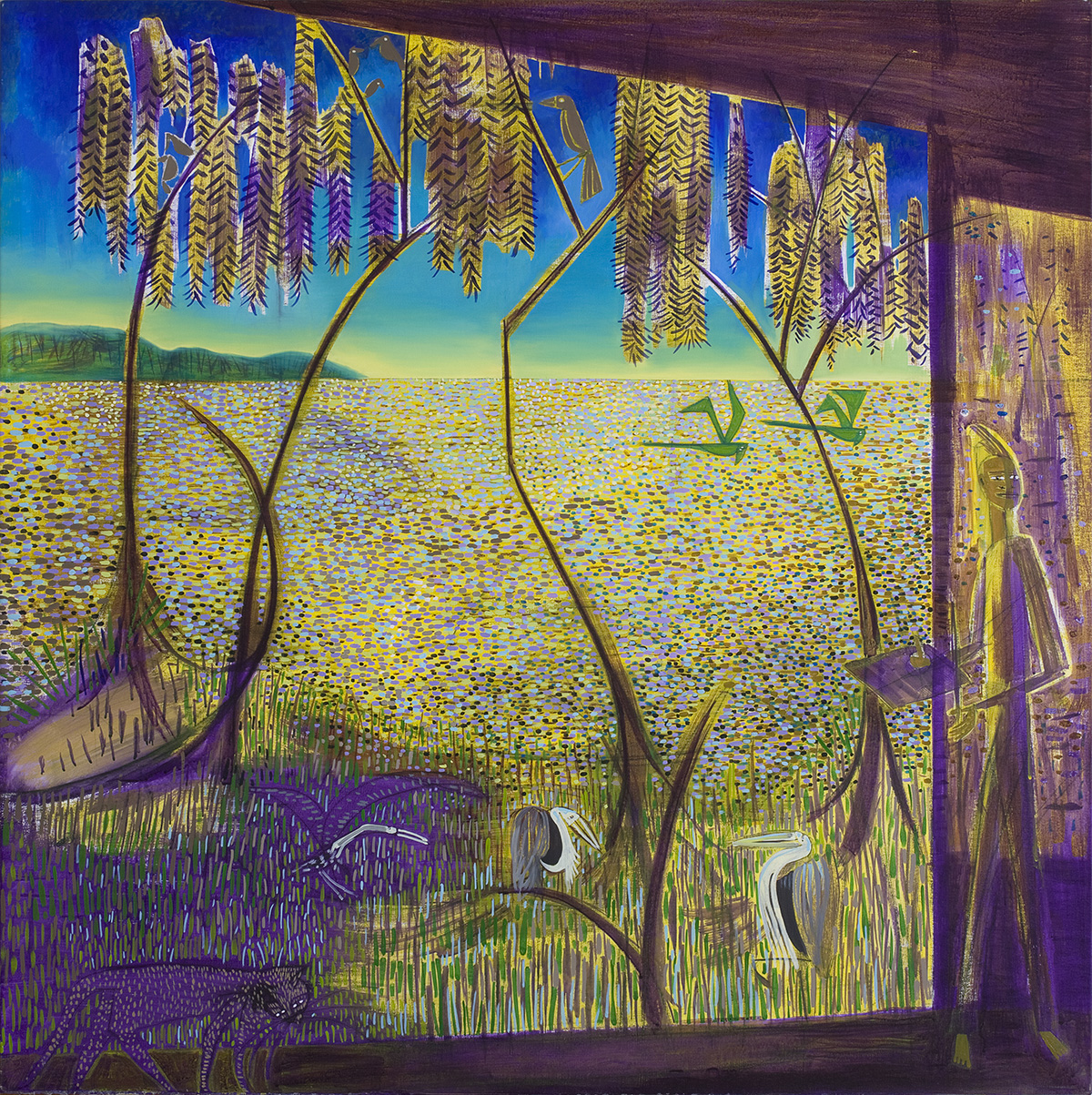

Restos Umbanda en la orilla del rio, 2010

Florencia Böhtlingk

Oil on canvas

59.05 x 57.48 in

TEXT

Every painting and the sole watercolor exhibited here, work towards the goal of getting to challenge some ideological basis, and that’s why Böhtlingk’s oeuvre attracts consecrated painters and a few responsible, worried intellectuals. Of the very scarce strange paintings that you can see in Buenos Aires, these are definitely the strangest.

We know that Böhtlingk can speak in tongues and that her paintings trade with signs that we don’t usually link with Buenos Aires, nor with a specific period, nor formally with her colleagues. I think of the visionary nuns, the most quaint ones, such as the Spanish abbess Juana de la Cruz, who used to speak Latin, French, Arabic and Basque during her ecstasies. But the problem with quoting moments of visionary delirium when talking about these paintings is that there’s no instant of dramatic rupture whatsoever. The show’s called La vida precisely because of that, because the weird thing about this body of work is its tendency to become a complete, worldly continuity; to just pass, like time does. To be beautiful or infinitely complex, like a migraine that feels like fog in the head.

Everything that lies within the social pact that we’ve defined as “contemporary art” (and more specifically, within its subsidiary known as contemporary painting), has nothing to do with these works, it does not belong in here.

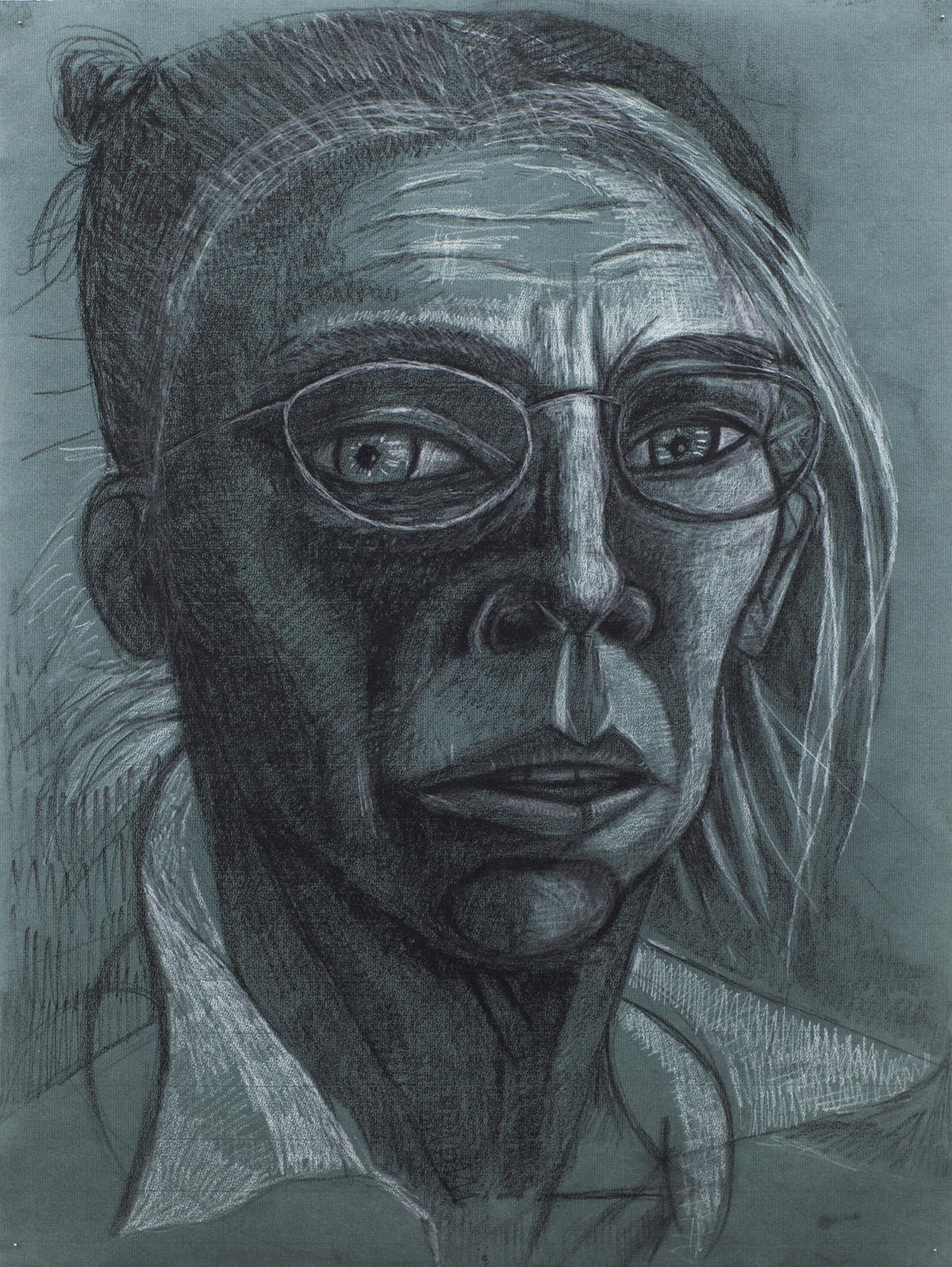

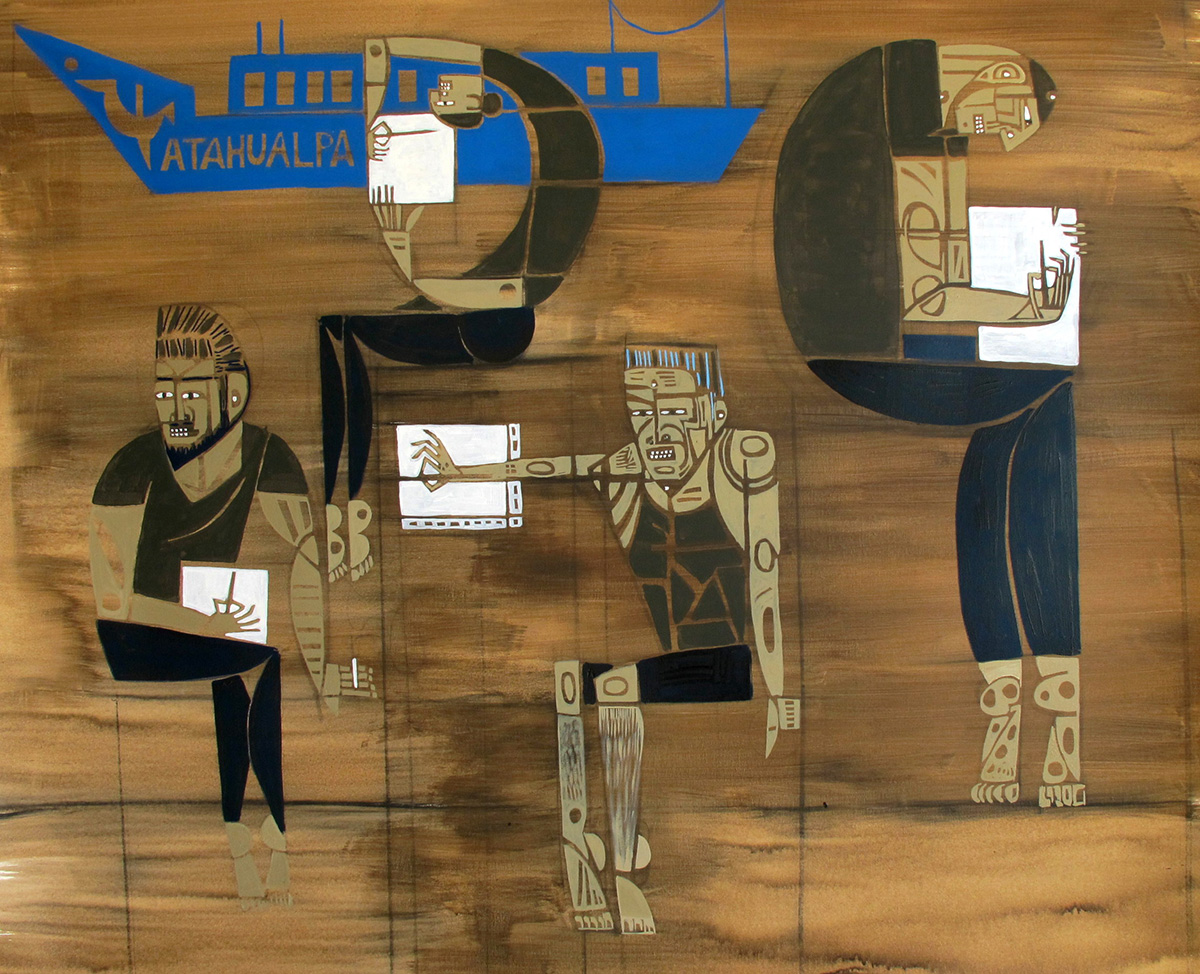

Refusing to look into the art system to actually make art is one of the fundamental dispositions of her work, but not its sole raison d’être. When, during some uncertain period of crisis, Böhtlingk decided to start “painting life” instead of, let’s say, just doing some paintings, she bent her neck and tried to look outside, tried to reach out to the things that were already in front of her: a boat, the sun’s soft muslin coating the river’s liquid ocher. This antagonism must not be interpreted as a reactionary reflex against the art world, nor as an exile: every shape that these paintings adopt is a byproduct of being constantly facing themselves, facing the images that they produce. The classical vice of the self-portrait, for example, faces Böhtlingk against herself and against her own painting. The big window on the top floor of her house confronts her with some wild parrots, and the painting puts her in front of those parrots once again, and, once again, in front of the painting itself. The same thing happens with her friends, with the books she reads, with the sailboats that slowly cross the river, with her neighbors, with the blood of a pig that was beheaded inside a shotgun shack.

So, we shouldn’t speak of a progressive debugging process inside these paintings, they’re not trying to achieve any perfection. Instead, they are a single part of a permanent conversation with the World and with the world that they themselves reflect and contain. An inner discussion about how to always be in the presence of the same things, about how to see, every day, through the window of an atelier, a few herons that stain the landscape with their white and their patience. In that sense, this is a painting of experience and because of that it reads into itself as a phenomena.

What Böhtlingk does, what makes all these paintings (and the lone watercolor) so strange, is her inclination towards never accepting any notion of naturality. Not the art of her own country, nor its formal codes, nor her epoch; not the anatomies, nor the inclemency of form, nor her own face.

Alejo Ponce de León