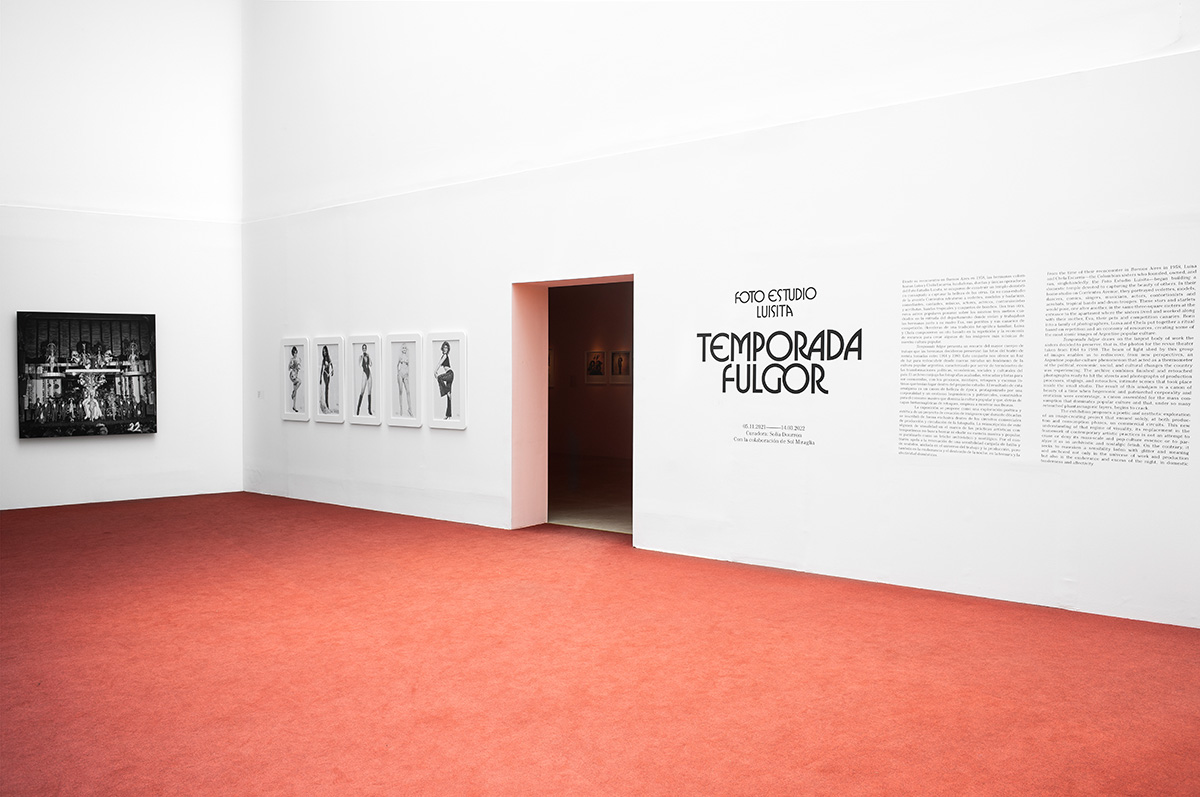

TEMPORADA FULGOR

FOTO ESTUDIO LUISITA

CURATED BY SOFÍA DOURRON IN COLLABORATION WITH SOL MIRAGLIA

MALBA

Buenos Aires, Argentina

NOV 3. 2021 — MAR 14. 2022

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

works

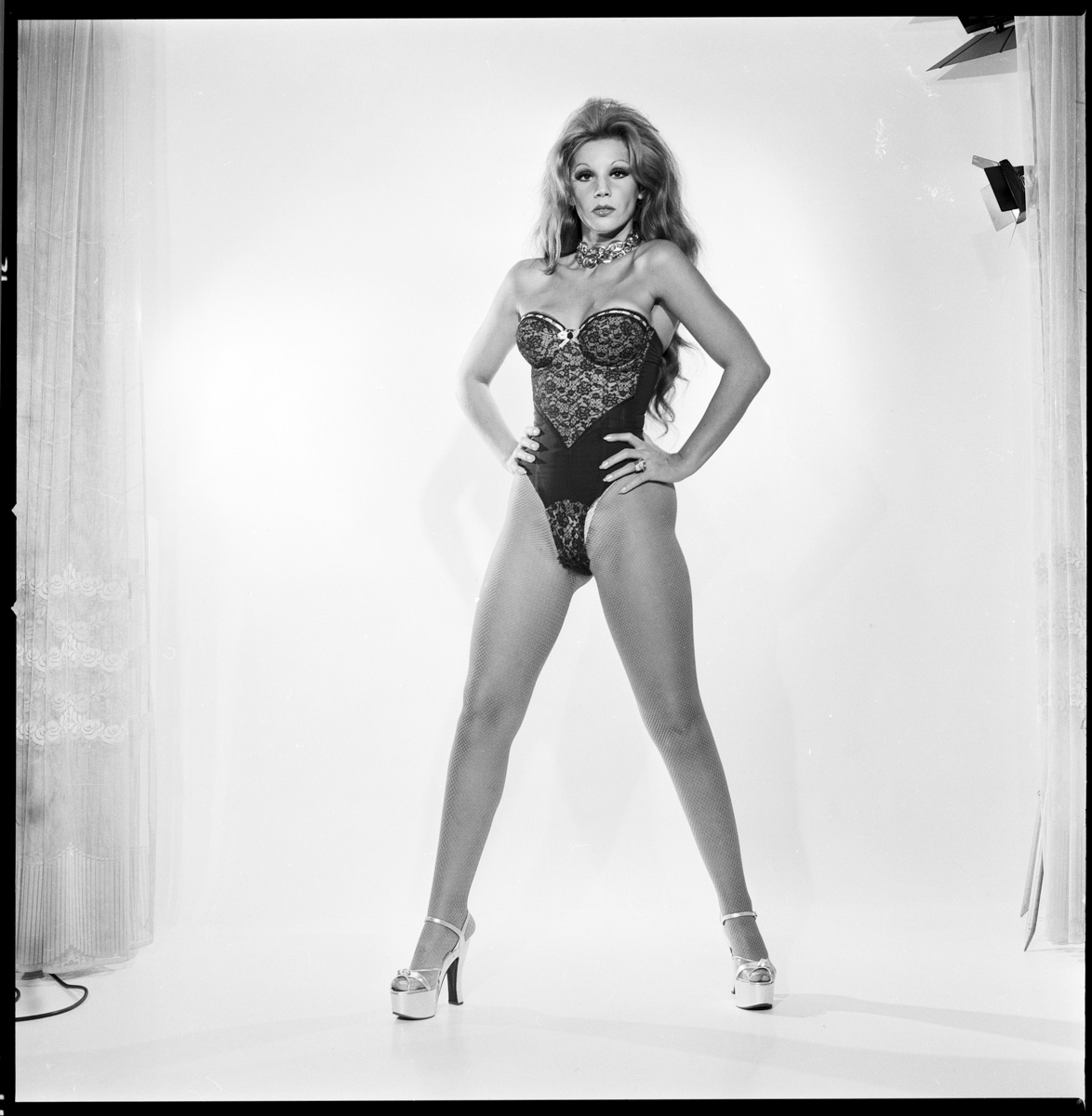

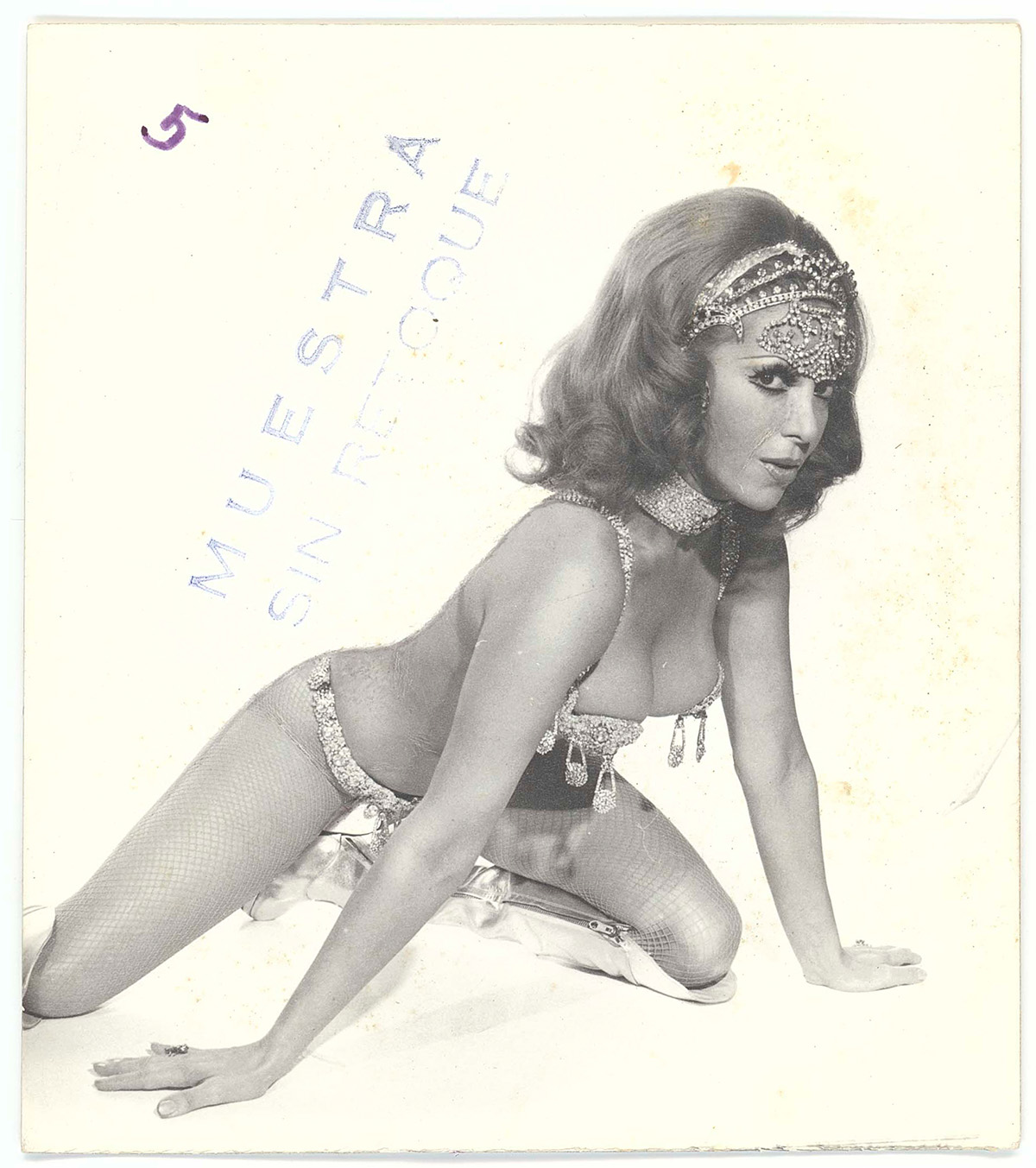

Moria Casan, 1973

Foto Estudio Luisita

Gelatin silver print; printed 2022

14.6 x 14.6 in

Edition 3 of 5

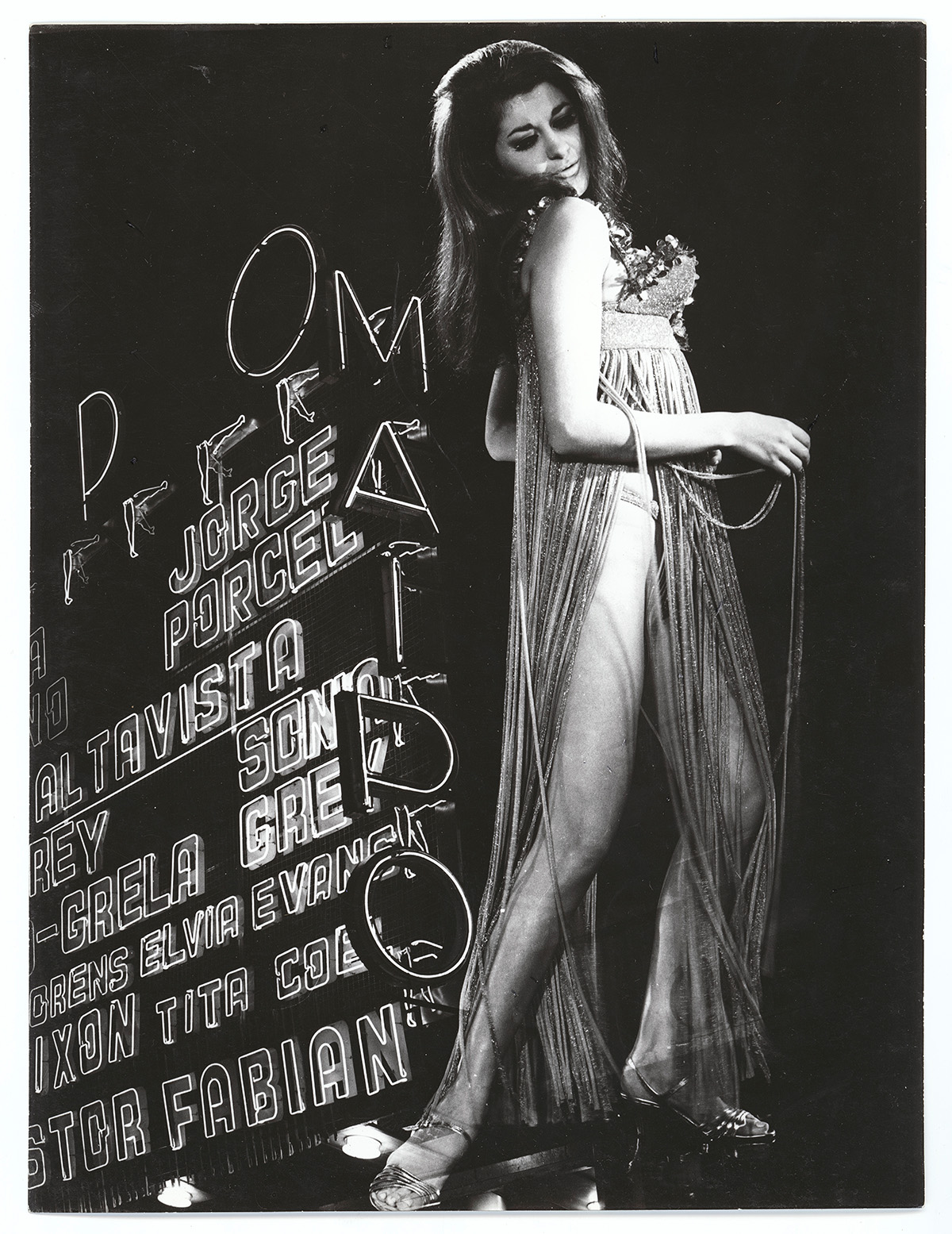

Susana Giménez, 1977

Foto Estudio Luisita

Gelatin silver print; printed 2021

14.6 x 14.6 in

Edition 2 of 5

Vanessa Show, 1976

Foto Estudio Luisita

Giclée print; printed 2021

19.7 x 19.7 in

Unique piece

Nélida Lobato, 1972

Foto Estudio Luisita

Giclée print; printed 2021

19.7 x 19.7 in

Unique piece

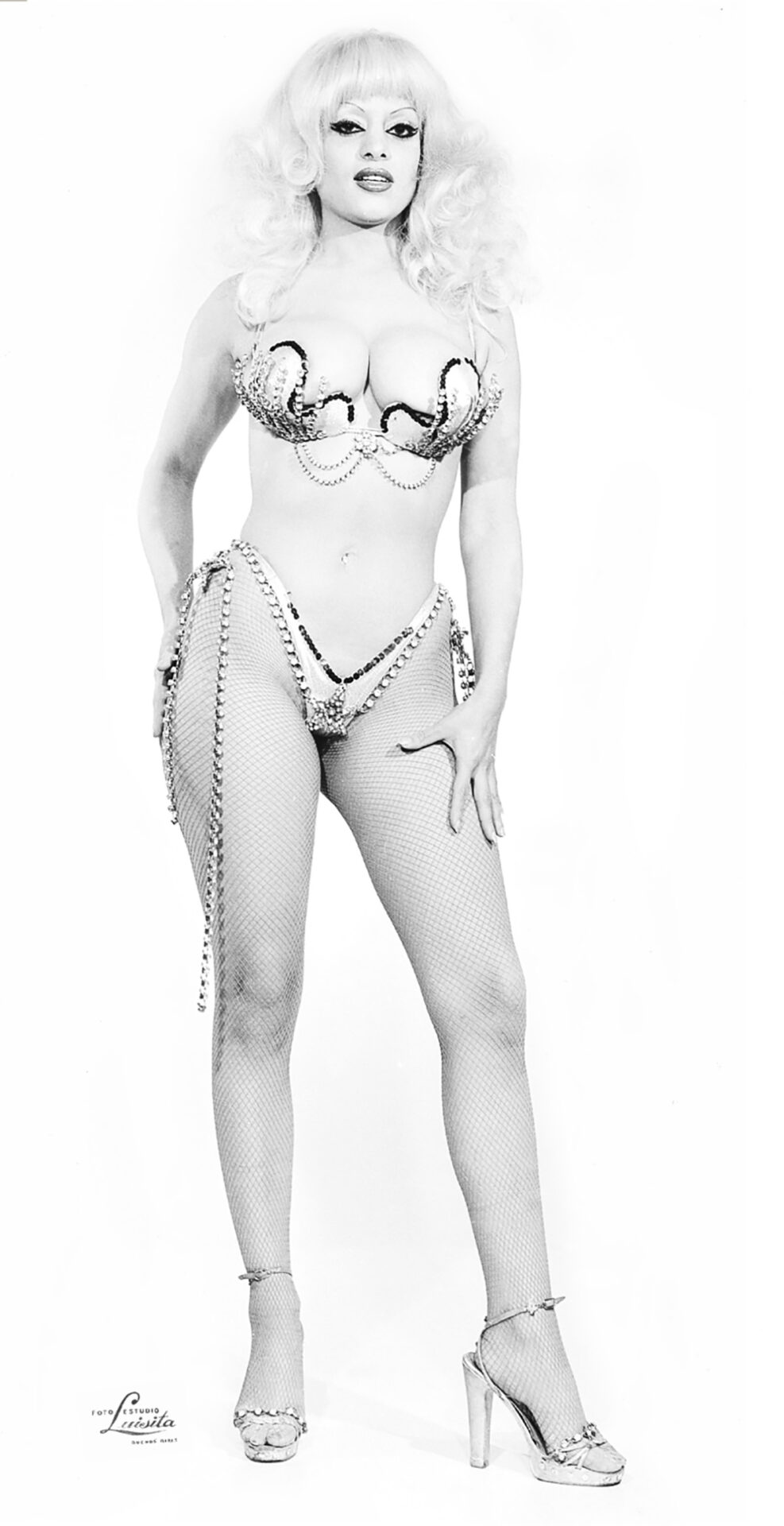

Untitled, ca. 1972

Foto Estudio Luisita

Giclée print; printed 2021

31,5 x 15.4 in

Unique piece

Lía Crucet, 1978

Foto Estudio Luisita

Giclée print; printed 2021

31,5 x 15.4 in

Unique piece

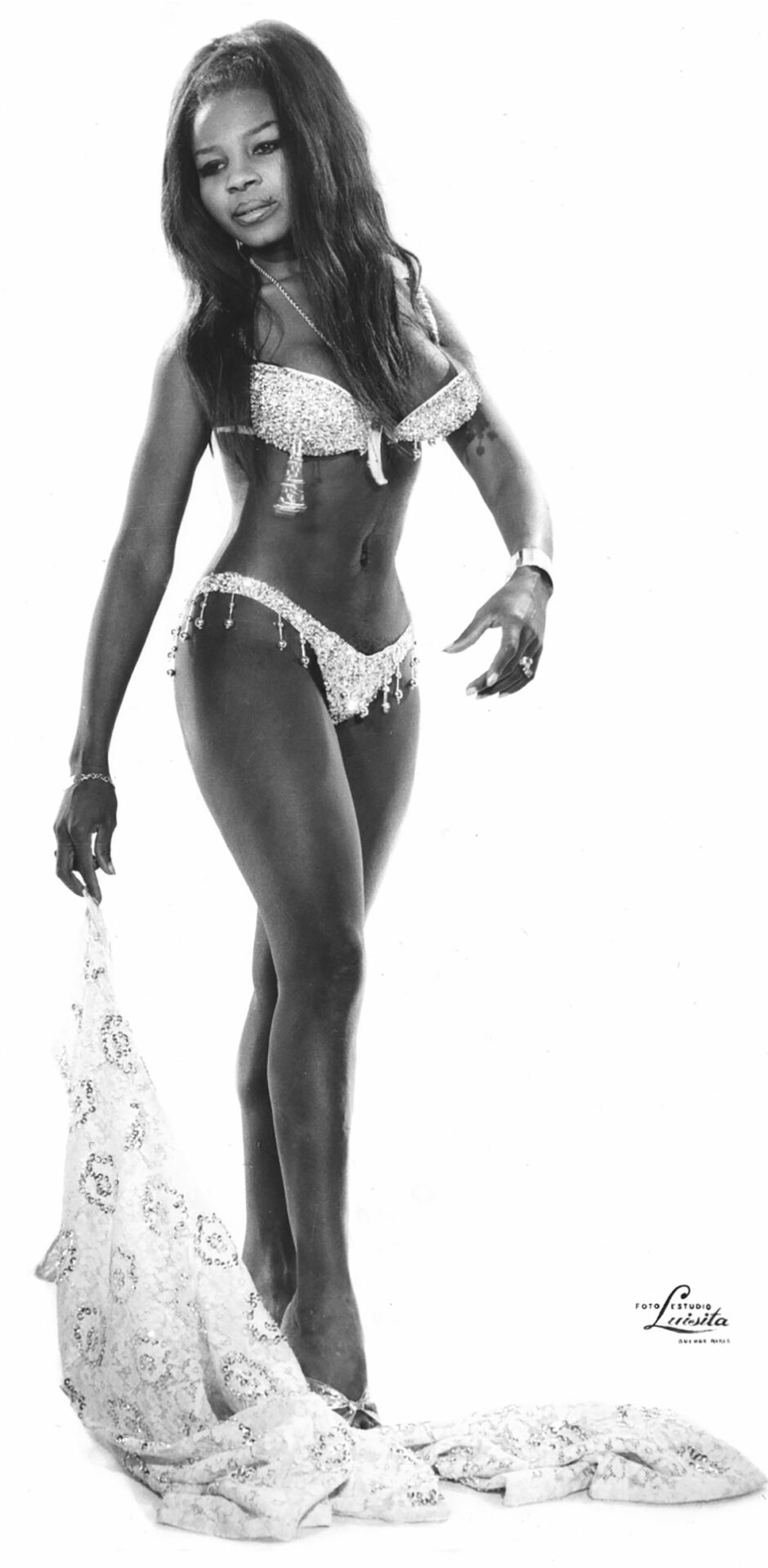

Zaima Beleño, 1968

Foto Estudio Luisita

Gelatin silver print; printed 2021

14.6 x 14.6 in

Edition 1 of 5

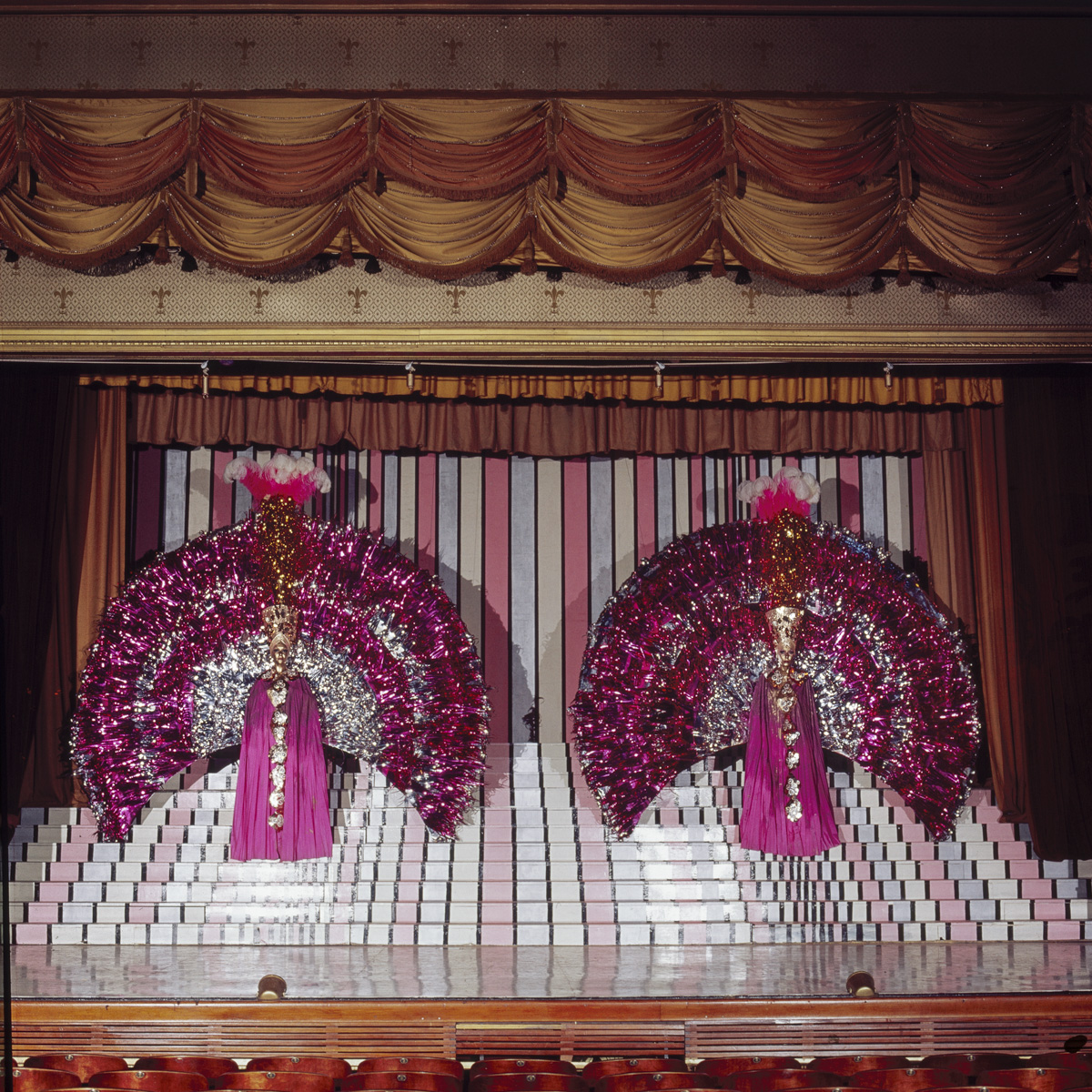

Ethel y Gogó Rojo, “El gran final”, Maipo Superstar. Teatro Maipo, 1973

Foto Estudio Luisita

Giclée print; printed 2021

35.4 x 35.4 in

Unique piece

Fantástica. Teatro Nacional, 1972

Foto Estudio Luisita

Giclée print; printed 2021

54.7 x 54.7 in

Unique piece

Pochi Grey, 1972

Foto Estudio Luisita

Gelatin silver print; printed 1972

9.4 x 7.1 in

Vintage print. Unique piece

Juanita Martínez con flor, 1964

Foto Estudio Luisita

Hand-colouring gelatin silver print; printed 1964

9.4 x 7.1 in

Vintage print. Unique piece

Diana, 1968

Foto Estudio Luisita

Gelatin silver print; printed 2021

14.6 x 14.6 in

Edition 1 of 5

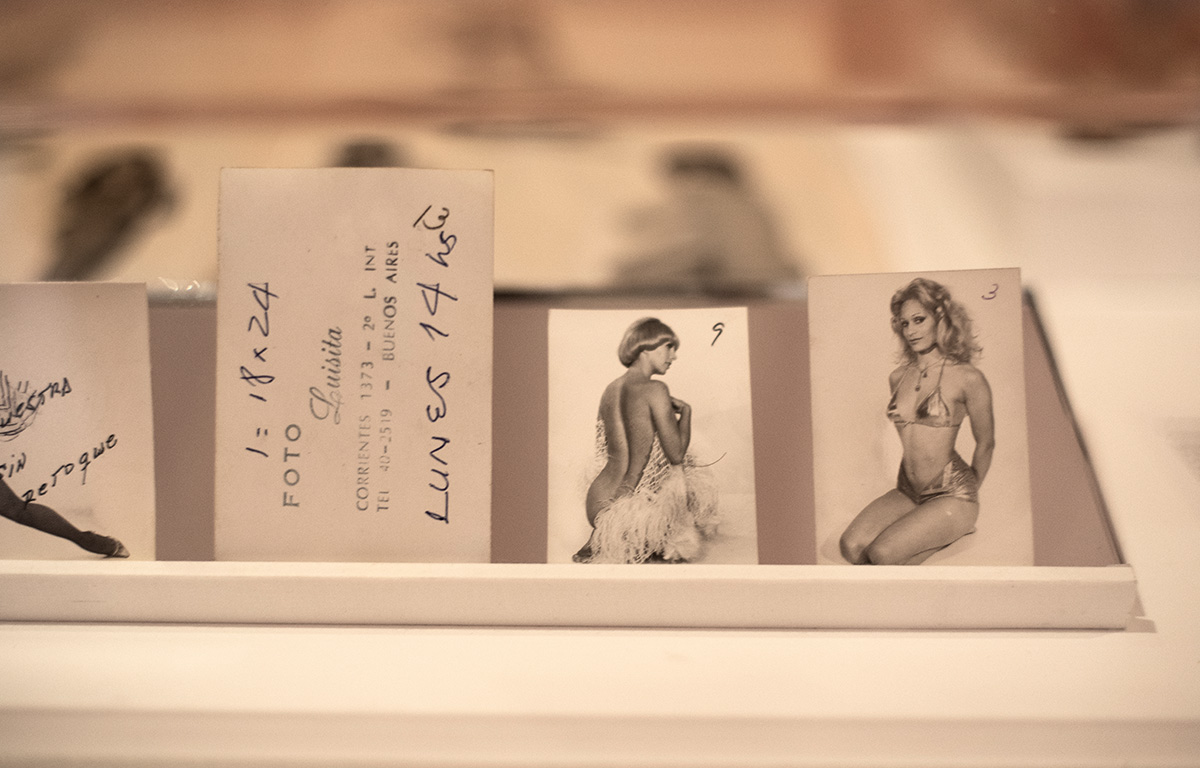

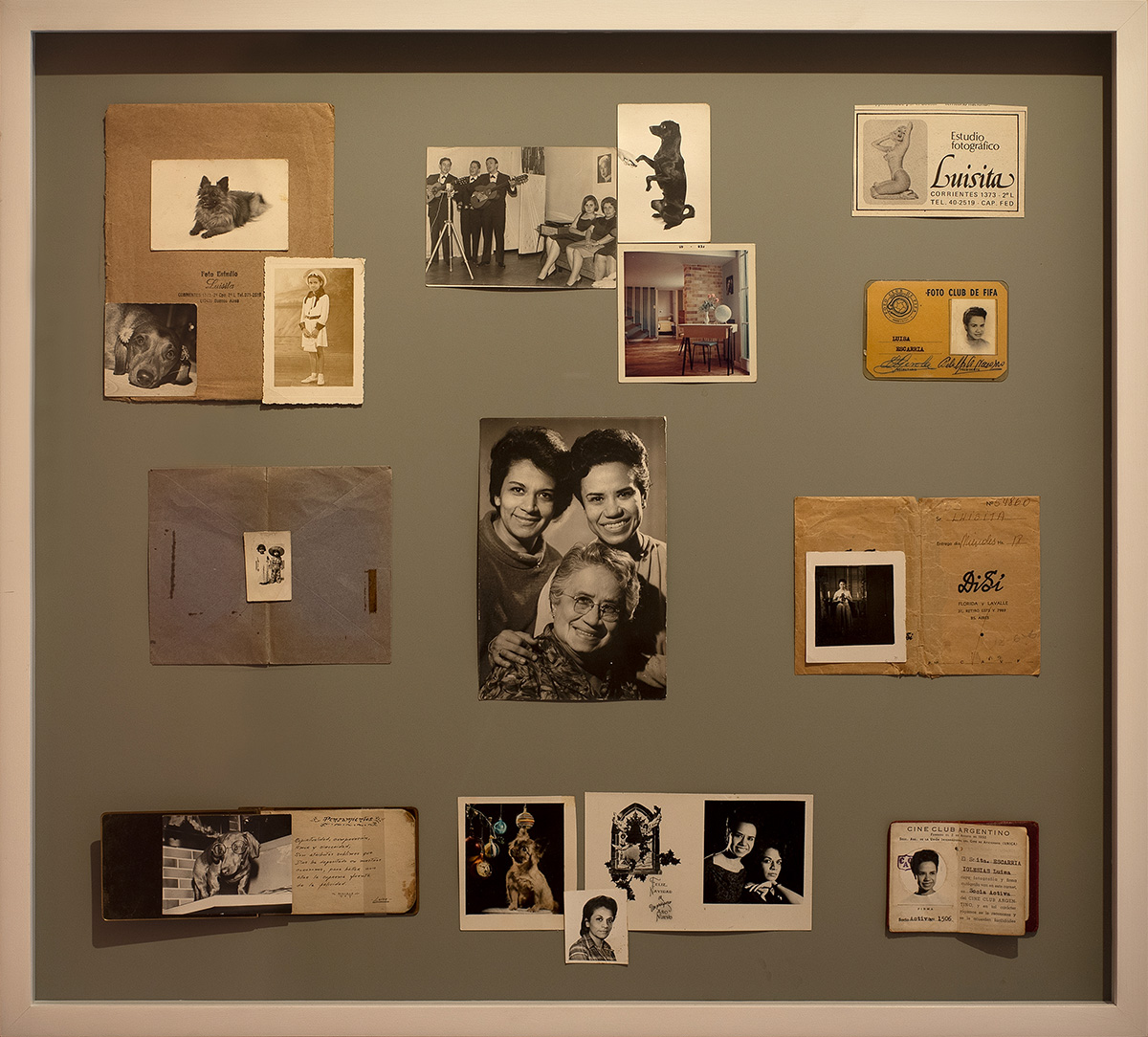

Photographs and personal documents of Luisa and Chela, n.d.

Foto Estudio Luisita

26 x 28.7 in

Vintage print. Unique piece

Ambar La Fox, 1978

Foto Estudio Luisita

Gelatin silver print; printed 1978

2.7 x 2.7 in

Vintage print. Unique piece

TEXT

Temporada fulgor

Foto Estudio Luisita Buenos Aires

By Sofía Dourron

Aperture: The Stars

From the time of their reencounter in Buenos Aires in 1958, Luisa and Chela Escarria—the Co-lombian sisters who founded, owned, and ran, singlehandedly, the Foto Estudio Luisita—began building a domestic temple devoted to capturing the beauty of others. In their home-studio on Cor-rientes Avenue, they portrayed vedettes1, models, dancers, comics, singers, musicians, actors, con-tortionists and acrobats, tropical bands and drum troupes; an occasional child might, in all their innocence, be portrayed on the same plush ottoman as the others. These stars and starlets would pose, one after another, in the same three-square meters at the entrance to the apartment where the sisters lived and worked along with their mother, Eva, their pets and competition canaries. Born into a family of photographers, Luisa and Chela put together a ritual based on repetition and an economy of resources, creating some of the most iconic images of Argentine popular culture.

This peculiar archive is a whimsical selection of the Escarria sisters’ vast production cre-ated over the course of their long career. Guided by memories, affects, and fetishes, and limited by the small size of their shared home, they themselves were the ones who did the selecting. The negatives, prints, and contact sheets that were not thrown out ended up in drawers along with café-sized bags of saccharine and teaspoons, in shoeboxes carefully arranged and stored under their beds, in little glittery boxes, in labeled envelopes and jampacked albums. The sisters catered al-most exclusively to the demands of show business, and revue theater—with its feather clouds and glitter, its elaborate choreography and popular music, its crude jokes and biting political commen-tary, its inconceivable acrobatics and even ventriloquists—was their preferred theme, the one they plunged into with most enthusiasm. They created images for marquees, billboards, handbills and other publications, and photographs whose fate was to act as support for the star’s autograph. This—the heart of the Foto Estudio Luisita archive—offers us an opportunity to blur the bounda-ries of the photography canon with its rigid limits between the commercial and the artistic, be-tween institutions and the vast world that lives at their margins, an opportunity to delve into the images of the body with no intellectual qualms or squeamishness.

Temporada fulgor. Foto Estudio Luisita, the show and the book published with it, draws on the largest body of work the sisters decided to preserve, that is, the photos for the revue theater taken from 1964 to 1980. The beam of light shed by this group of images enables us to rediscover, from new perspectives, an Argentine popular-culture phenomenon that occupied the stages on Corrientes Avenue starting in the nineteen-twenties. It acted as a thermometer of the political, economic, social, and cultural changes the country was experiencing. Furthermore, these mass-circulation images draw back the curtain to show what was going on behind the scenes, making us party to their highly personal construction. The archive combines finished and retouched photo-graphs ready to hit the streets and photographs of production processes, stagings, and retouches, intimate scenes that took place inside the small studio.

The result of this amalgam is a canon of beauty of a time when hegemonic and patriarchal corporality and eroticism were centerstage, a canon assembled for the mass consumption that dominated popular culture and that, under so many retouched phantasmagoric layers, begins to crack. But neither the canon nor the mass circulation of these images is what makes them iconic. That, rather, is the working of Luisita’s tender and overarching vision—she captures subjectivities through gestures that range from an imperceptible blink of the eye to the choreographic display of a monumental body—and Chela’s technical skill. Thanks to them we have Nélida Lobato sheathed in a tiny red onesie; Nélida Roca immersed in a feather boa; Norma and Mimí Pons with their blond souffle-like hairdos; Ethel and Gogó Rojo golden from head to toe on the legendary Maipo2 stage.

Temporada fulgor binds the world of show business and the domestic world, Corrientes Avenue and the sisters’ home-studio, evidencing the intersections and divergencies between the two on both material

and conceptual levels. Silent clashes between the Escarria matriarchy and a doggedly conservative and

patriarchal society are revealed, as are the clashes between the monu-mentality of bodies covered in feathers and the studio’s homey warmth, the luminous Luisita and the images’ mass circulation, the transformations in the politics of the body and desire and Che-la’s retouching and image-manipulation techniques. In short, a young topless Beba Granados cov-ering her torso (that is, her tits) with Diana, the Escarrias’ weiner dog.

The Studio: Photographic Gymnastics

Katia Iaros in a perfectly straight lunge against a white background. Her right knee crosses her left leg. The

toes of her stiletto heels barely touch the floor. One hand rests calmly on her knee and the other, wrapped

in a glittery band, lies by her side. The colossal hairpiece floats above her erect neck (the feathers at the

top can barely fit into the frame). Luisita is forced, by the smallness of the apartment, to perform her usual

photographic gymnastics. She shoots her Hasselblad and re-veals the enormous and complex world that

revolves around the adorned body of the vedette. The infinite confesses its own finitude, and peach lace

window curtains do their best to serve as theater curtain on a domestic stage. Like eager theatergoers, the

lights and camera flashes look straight at Katia; a cable hanging down to the left in the foreground clamors

for attention; the calendar, illus-trated with two parrots, on a wall in the background to the right brings time

to a standstill at the exact moment of the shoot.

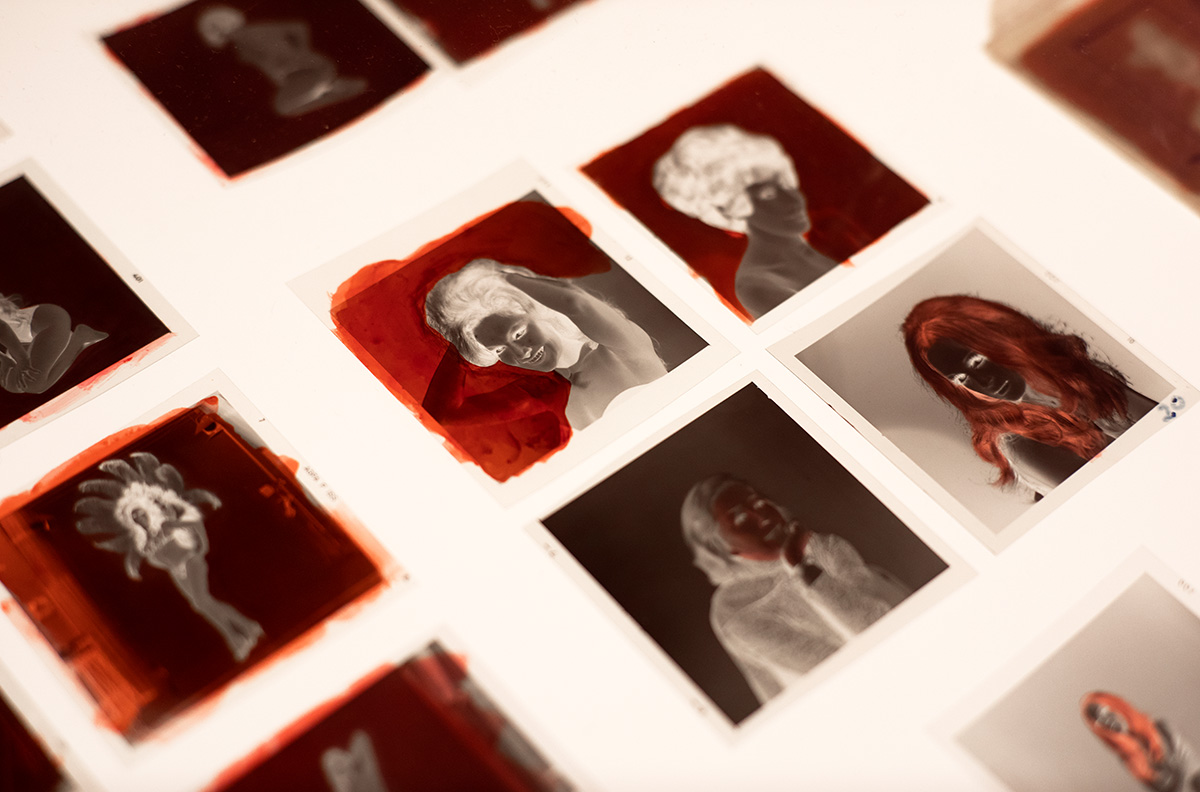

The sessions at Foto Estudio Luisita yielded tiny negatives (just 120 mm) that take in not only the posing

subject, but also the entire universe astir around that subject. In them, objects come to life, turn into agents,

and webs of meaning as sticky as spiderwebs are spun, titillating webs of personalities, eras, objects, and

processes whose unlikely encounter is a treasure in and of itself. Many of these negatives were retouched:

layer by layer, red ink eliminated any information that seemed irrelevant. Nonetheless, behind the ink we can make out, if just barely, the removed silhouettes that, like ghost, try to return to the light. Those still-intact negatives are what best re-veal, what show with greatest intensity, all the life that the sisters managed to capture; they thus become bearers of a cultural memory, instruments of work, affective archives.

As opposed to the images that left the studio in final form, without the slightest trace of where they came

from, the negatives that were not altered tell their own stories and bear marks of the conditions in which

they were produced. They even betray the tools and processes that made their existence possible: flashes,

lights, cables, hands that come in the frame and do something to the bodies to extract every last bit of

beauty they have to give. Chela’s body—her back to Mariano Mores as she holds a yellow filter in front of

a light to keep the magenta jacket from obscuring the musician’s charisma—takes on a new dimension in

the construction of an image that circulates anonymously in the field of mass culture. That body shows

labor, collective creation, individual tenacities that converge in the space—nothing could be further from the

anonymity and hygiene of the imaginary of industrial production.

Layers of another sort are at play in the negatives that have not been intervened. These lay-ers narrate a

hodgepodge of minimal stories and small relegated gestures that together assemble a complex narrative

riddled with contradiction and paradox. They capture the encounter in a single space between diverse

subjectivities, each with a biography, background, and everyday life; be-tween glamour, the poetics of the

night, the changing politics of sexuality, and the nascent embod-iment of desire; the tensions part and

parcel of show business, an immigrant matriarchy and its affective economics, a multispecies community of

humans, doggies, and birds; the warmth of the home, spirituality, and religious morality. In disinterested and

surprising fashion, these images offer us a concatenation of snapshots that attest to the transformations

facing Argentine society even today.

By examining this working material now made public, we are able to reconstruct a fragment of the history

of patriarchal and heteronormative demand enacted on bodies. It is part of the symbolic legacy passed

down to us, and it represents, among other things, masculine and heterosexual dom-ination as accepted

social norm. The bodies and faces of stars were retouched without a second thought, just as fans, flashes,

and curtains were edited out. Tummies and hips were slimmed; cel-lulitis, wrinkles, creases, and dark rings

under eyes erased; perfect curves and porcelain skin in-vented. The contrasts in the archive’s various

materials (negatives, retouched negatives, and vin-tage prints) evidence changing ways of conceiving and

consuming bodies and media representa-tions that influenced the construction of desire as well as how

generations of locals perceived themselves. But something slips through those norms, leaks in and starts to

strain the surfaces of the stereotypes. Little by little, it works away at gender mandates to make room for

dissident sex-ualities and bodies that rebel against normativity.

The narrative contains an arch of images that spans from seminude vedettes and models doing acrobatics

with boas, nipple pasties, doggies, and balloons to cover themselves to Mariola Bosse showing off her gifts

like full moons just barely wrapped in a scrap of silver fabric; it elo-quently illustrates transformations in

the politics of sexuality. What Ezequiel Lozano describes as a “discreet revolution”3 took place in Argentine

theater in the nineteen-sixties between a model of domesticity associated with family normativity and

developments like divorce, women’s entry into the workforce on mass scale, new discourses on sexuality,

and a weakening of gender preju-dice and double standards in, for instance, the rejection of the longstanding association between decency and female virginity.4 That double standard is particularly poignant in revue theater, where patriarchal logics of organization and domination reign but women are the ones in command on stage. Cis sexuality is a primordial topic of jokes and stand-up routines, but they are per-formed on occasion by dissident identities and sexualities embodied in dance troupes. We thus see, from negative to negative, how lines of flight emerge, lines that escape a morality still con-servative and phobic and censorship and institutional violence at the hand of civic-military governments.

The image of a topless Adriana Parets crowned like a peacock by an enormous halo of blue and white feathers and flanked by a body of seminude dancers against an absolutely Pop curtain forms part of the narrative of the hypersexualization of women and of show business. It is a story of contrasts and contradictions that swings back and forth from the sexual-liberation movements of the sixties to the incipient encroachment of the free market and the neocolonial commercializa-tion of bodies. This single image epitomizes the processes that, in the nineteen-eighties, would overthrow the hegemony of revue theater as supreme space for the public display of bodies and sexualities; it would fall to television programs that would take those same precepts to the dining rooms, living rooms, and bedrooms of all Argentines. The body, here, becomes agent of history, historiographic instrument par excellence; revue theater, its vehicle; and the Foto Estudio Luisita archive, one of its best-kept repositories.

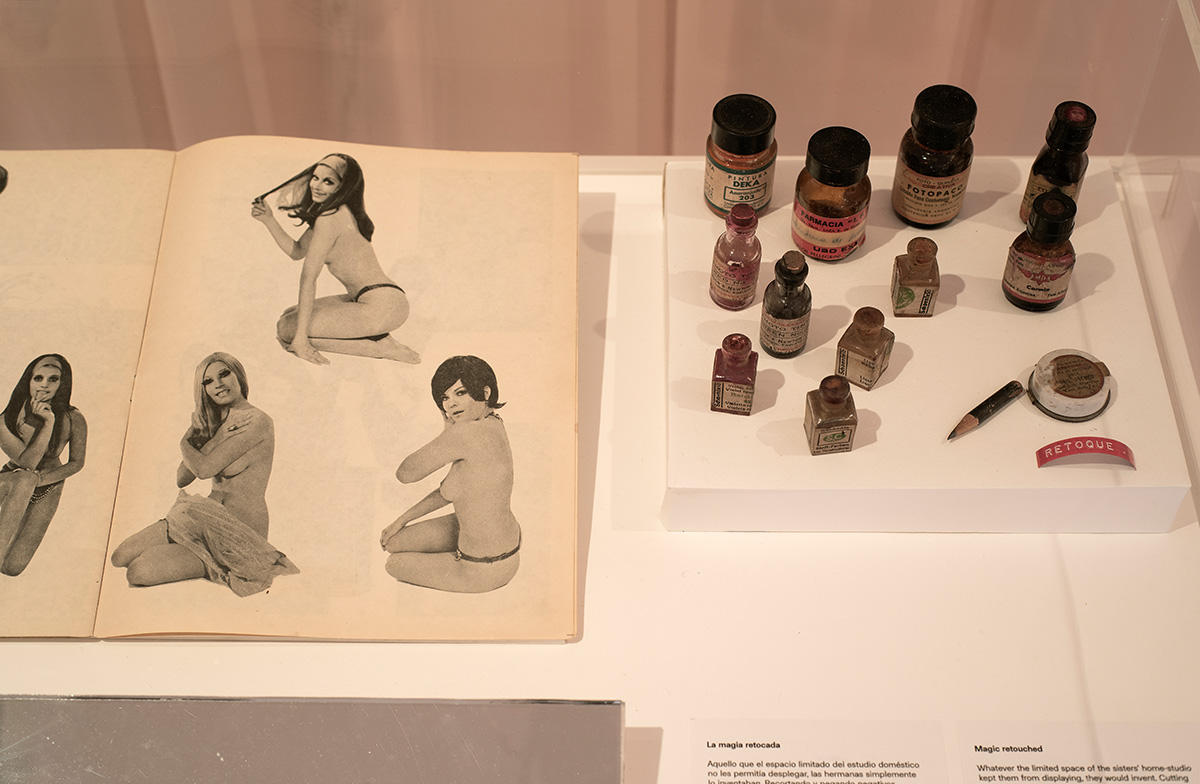

Intermediate Frame

Covered in bright tassel that hangs down from a bra with flower trim, Pochi Grey, against a black background, gently stretches her right leg and, seductive, looks over her shoulder. The neon lights of the Maipo theater marquee accompany the movement of her leg; they fall toward the left edge of the photograph and announce Jorge Porcel in Altavista. Chela’s staging monumentalizes the vedette, who seems to storm the city like a glamorous Godzilla, taking Corrientes Avenue with her and gobbling up anything that crosses her path. The image is a perfect cross of inside and outside, of studio portrait and street photography. It is one of the only photographs in Foto Estudio Luisi-ta’s oeuvre that was taken in the street. It is a perfect cross of fiction and reality.

Whatever the limited space of the sisters’ home-studio kept them from displaying, they would invent.

Cutting and pasting negatives, layering and retouching them, or altering the color by hand, Luisa and Chela

created images that sometimes border on the surrealist: a tiny José Marrone lounging on a telephone three

times his size; the entire Bombos Ranqueles troupe floating in space; Juanita Martínez posing next to a giant

cocktail and flower. While the sisters deploy their greatest staging resources in their work with tropical

bands, making musicians and instrument fly over mountains, cross scores, and pose beside Caribbean palm

trees, their stagings for revue thea-ter playfully bring something of the performance’s magic of motion to

the static image on flat paper.

Revue: Glamor and Resilience

The restless audience fidgets in their seats, their shoes tap the wood floor, the racket sweeps through

the hall like waves, and light bounces off the mirrors and golden surfaces that outfit the main arena of the

Maipo theater. The red velvet curtain is drawn heavily to reveal an invraisemblable image. The Rojo sisters,

motionless on a stairway: golden faces, golden crowns, magenta capes, ruffle hairpieces in like tone topped

with feathers shield their backs. In the shadows, Chela points the heavy Metz flashes she has hauled down

from her house, while Luisita shoots Koda-chrome (color slides film) with her Hasselblad camera. Neither

one knows for sure what they will capture. They shoot, and then shoot again and again and again. The

Rojos take off their capes and—bodies golden from head to toe—walk down the stairs. The Rojos dance.

The Rojos exit the stage.

Despite their boundless imagination—or perhaps thanks to it—the Escarria sisters rarely left their apartment. When they did, they were usually heading down to the Maipo theater, where Foto Estudio Luisita was tasked with registering the sets for all the performances. These color slides and black-and-white negatives were carefully kept for decades in a little box labelled “Exte-riors” and “Maipo.” Once placed on the screen of the negatoscope, these slides and negatives bring to the surface sumptuous sets, glamorous wardrobes, enormous dance troupes, impressive solos, baffling scenes, distracted dancers, skewed sets, fallen hairpieces, and even members of the audience where they shouldn’t be.

These images are the bearers of one world that is coming to an end and another that is emerging, a golden

age burning out and vedettes retiring as nascent stars rise; new forms of cul-tural consumption, televisions

by the millions, pop culture, and the sexual revolution that clashes with military governments, censorship,

and institutional violence. The original aim of revue thea-ter was to provide an exuberant lift to offset

everyday hustle and bustle and the unease it brings. But, as its name indicates,5 it also reviewed current

events. It managed to survive the ups and downs of Buenos Aires life, resiliently adapting to whatever it

came up against. It might have lost poignancy, but it managed to stay open and evade censorship. It paid

fines for the jokes told by its comics and got along with the military officers6 who sat in its box seats and

seduced its sex-symbol stars. It did not give in until the nineties under the weight of television and media

culture. Transformations in the media and image production also brought a rupture in the work of Foto

Estudio Luisita and, especially, in its tie to revue theater. The sisters visited the Maipo less and less often;

theater stars stopped visiting the studio making way for a new kind of subject.

Both revue theater and the images that document it form part of popular culture, and as such they were,

for a long time, ignored by the cultural systems that determine and dominate the fields of the arts and

the academy. Paradoxically, today these systems seek out those marginal archives and characters

obscured by time to renew their own languages and canons that were so hermetic for so long. Negative

by negative, the Foto Estudio Luisita archive shows the enormous contribution both revue theater and the

sisters’ studio made to our visual culture, to the formation of our collective identities, to the construction—

as well as the deconstruction—of subjectivities. From their first ventures into a field dominated by men, the Escarria sisters captured a silent force with which to undermine, even involuntarily, the stereo-types that both Colombian and Argentine society would impose on them. In the same meticulous way they captured extraordinary scenes and retouched them to the point of exhaustion, this photo-graphic duo, these image workers, continue to take apart myths and mandates, even the mandate of the intellectual, modern or contemporary, photography.

Last Dance

Temporada fulgor proposes a poetic and aesthetic exploration of an image-creating project that ensued

solely, at both production and consumption phases, on commercial circuits. This new un-derstanding of that

regime of visuality, its re-placement in the framework of contemporary artistic practices is not an attempt

to erase or deny its mass-scale and pop-culture essence or to paralyze it as an archivistic and nostalgic

fetish. On the contrary, it seeks to reawaken a sensibility laden with glitter and meaning and anchored not

only in the universe of work and production but also in the exuberance and excess of the night, in domestic

tenderness and affectivity.

The Foto Estudio Luisita archive holds within it a small revolution of micro-stories: wom-en who, through

their work and minimal gestures under the cover of daily life, shattered the patri-archal mandates of their

time; a field of popular culture that resists submission to the banalization of superfluous readings; bodies on

display on the stage in choreographies that empower beyond the scrutinizing gaze. We find as well a burst

of honky-tonk luxury and joy that, to paraphrase Emma Goldman, seems to declare, “If I can’t shine, I don’t

want to be part of your revolution.”

English version: Jane Brodie

1 The word vedette refers to revue theater principal dancers and sex symbols.

2 Translator’s note: A classic revue theater located at 449 Esmeralda Street in downtown Buenos Aires.

It opened to the public in 1908.

3 Lozano, Ezequiel. Sexualidades disidentes en el teatro: Buenos Aires, años 60. Buenos Aires, Biblos, 2015.

4 Cosse, Isabella. “Ilegitimidades de origen y vulnerabilidad en la Argentina de mediados del siglo XX,” in Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos, n° 1, 2007, pp. 1-2.

5 The etymology of the word revue lies in the he French word for “review,” as in a “show presenting a review of current events.” See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revue#Etymology

6 Translator’s note: Argentina was under the rule of a blood civic-military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983.