PIEDRA, TIJERA, PAPEL

LETICIA OBEID

CuraTED BY FEda BAEZA

AGO 9. — SEP 15. 2018

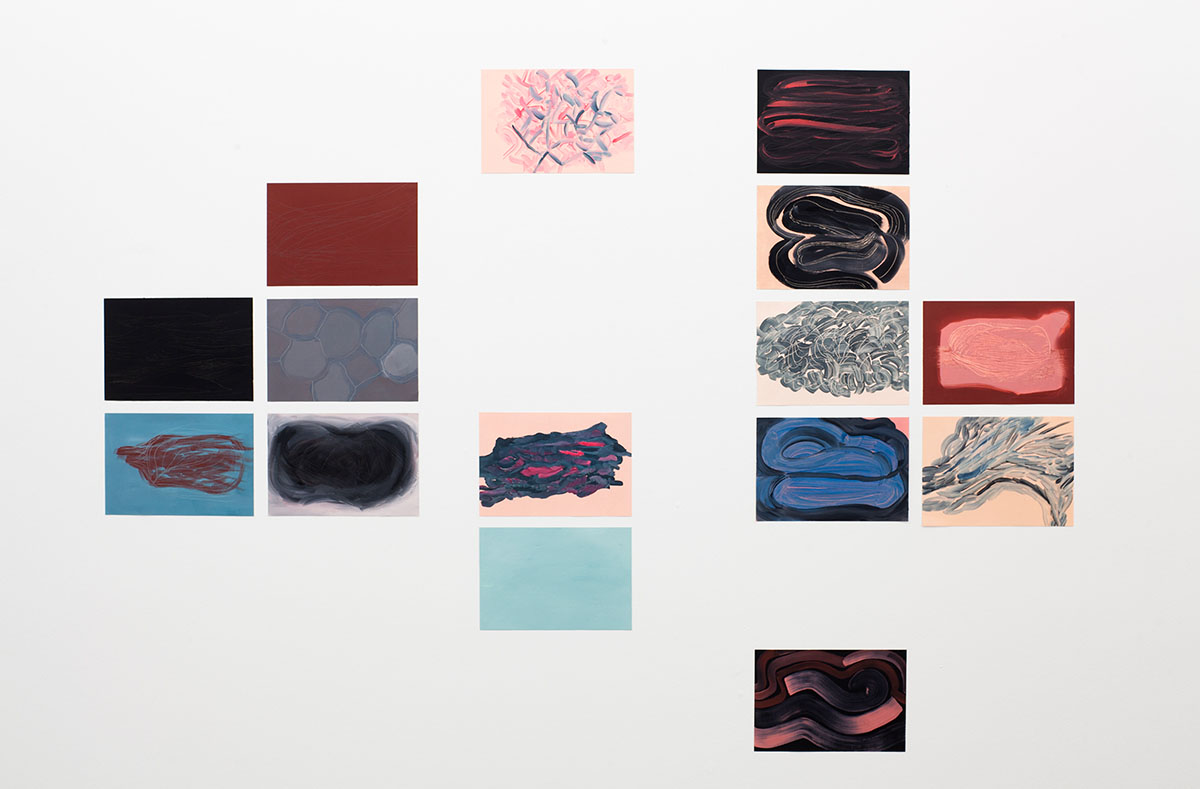

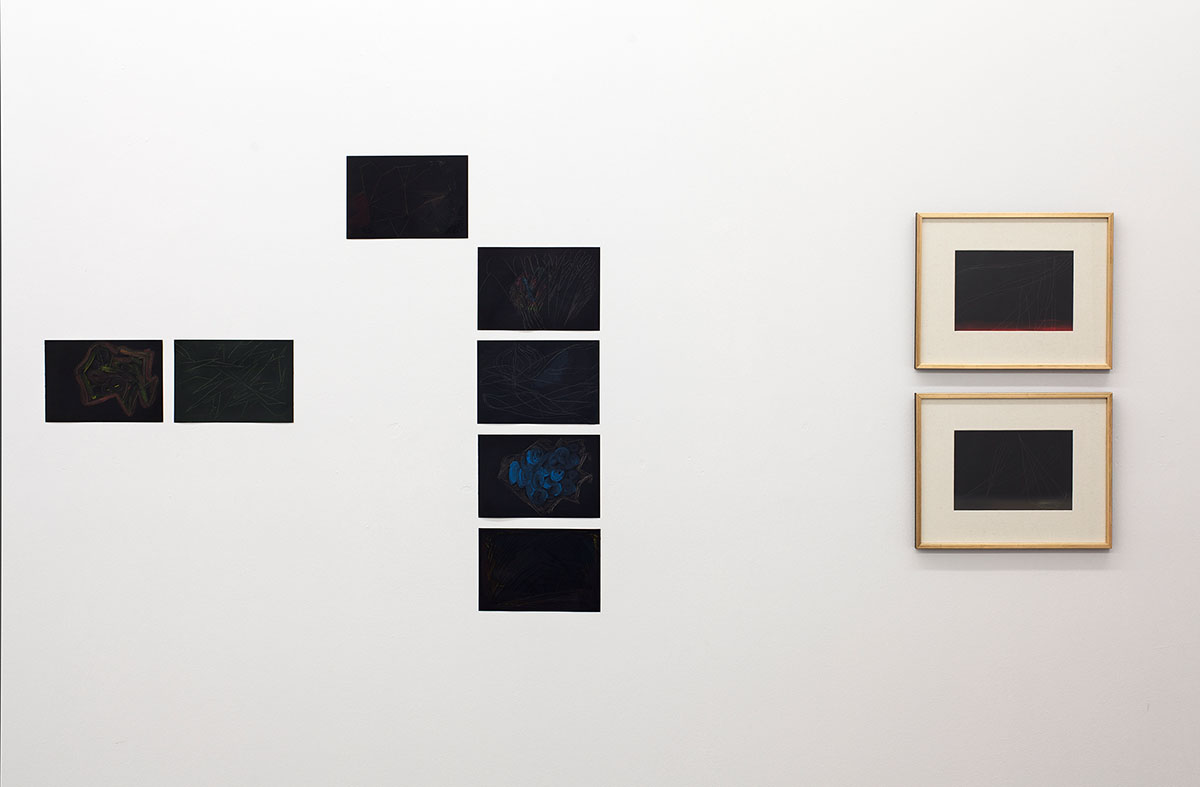

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

WORKS

TEXT

rock, scissors, papER

I

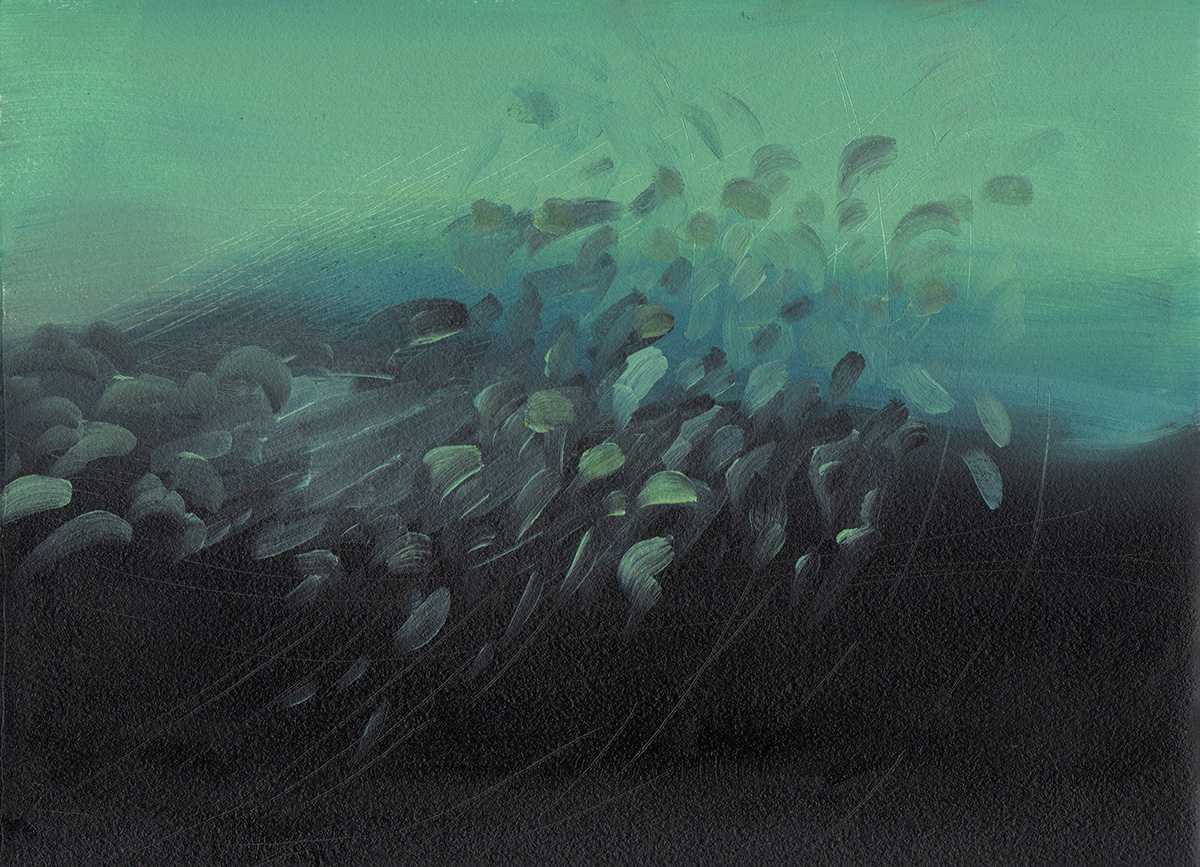

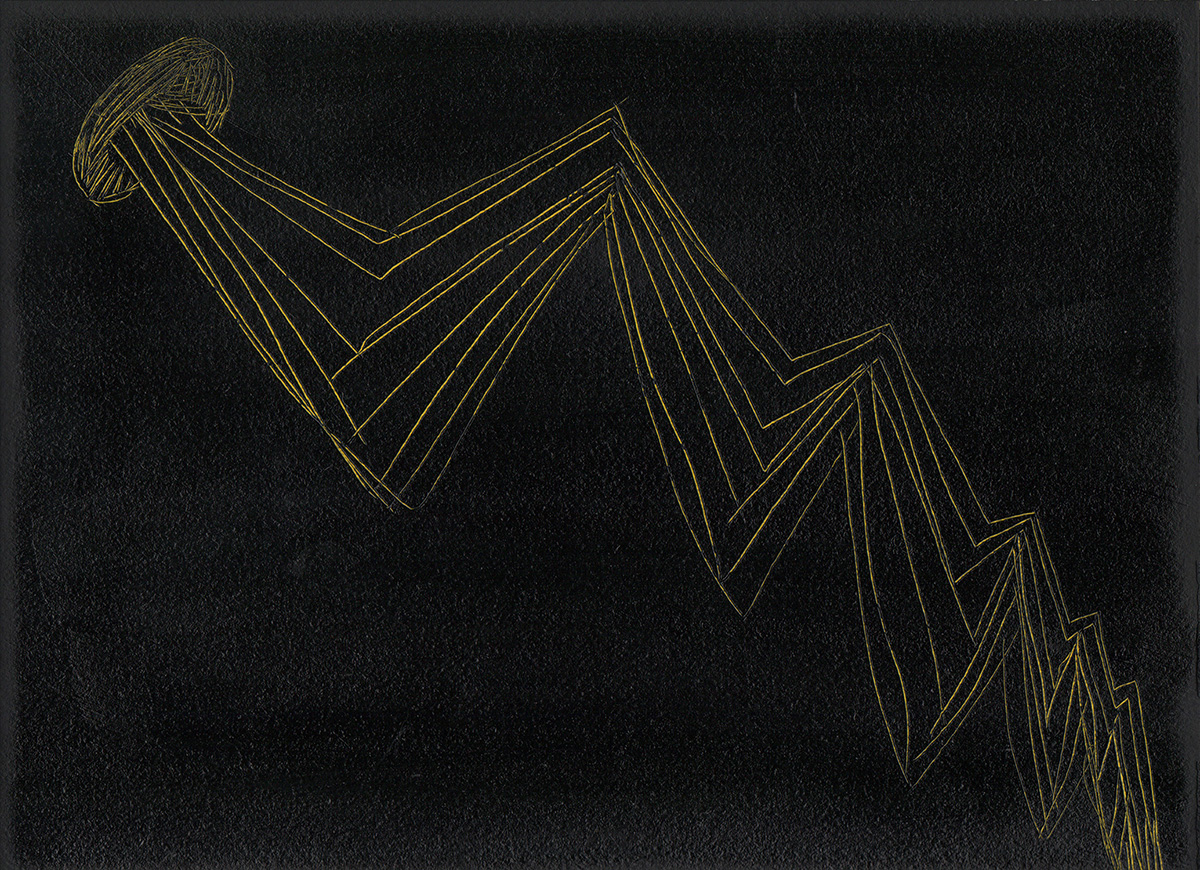

It was the early 2000s, and Leticia was doing works on small canvases. Her support of choice, actually, was canvas on hardboard—that material so common in the studios of painting students. Like many artists of her generation, of my generation, she opted for accessible materials, for humble formats that were easy to pay for and accumulate. She used murky colors, shades of brown, ochre, gray barely lit up by a slightly saturated tone. She would squeeze every last smidgen of paint out of the tube. She would use the bristleless end of the paintbrush to scratch at still fresh layers of Alba oil paint. She would dig into layer upon layer of color until you could see—in some cases—almost bare fabric underneath. Those graphisms were made slowly and mechanically like someone scribbling on a calendar while talking on the phone. The patterns would repeat in layers, and sometimes the accumulation yielded slight mutations that would gradually alter the regular flow. She composed this series of swirls as if testing out a posture, a gesture, as if imitating a signature. She let herself be swept away by a certain inclination to the ornamental, by a way of making immersed in a floating attention, a skewed impulse that hovers on the surface until it happens upon an inflection in the line. Thus she would, perhaps unwittingly, avoid the strident dramatic gesture so associated to those temperamental painters from the eighties with whom she had studied at art school in Córdoba.

II

Self-taught, intrepid, groundbreaking men of humble birth who made something of themselves. A great many anecdotes paint the almost Western-movie image of the Ameghino brothers, Florentino and Carlos. In the Pampa, a place seen as one of history’s barren tundra, the duo embarked on a frenetic raid full of zany adventures. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, they brought to the surface the paleontological landscape hidden in a land fertile for farming and livestock, a region recently annexed as part of global capitalism. The tales of their adventures are not short on heroic feats or battles to the death. Their run-ins with Francisco Pascasio Moreno, the leader of the rival team of scientists, are still remembered. The Ameghinos did not hesitate to record false locations in their field notes to throw off their competitors. Florentino also had heated debates with North American naturalist Aleš Hrdlička in which he defended his theory that the human race had begun in South America. His research attempted to prove that during the Early Eocene Age a group of hominids from Patagonia migrated to the north of the continent to then populate the rest of the planet.

His stratigraphic chart of the Pampas—that is, the chart of the layout of layers of earth that evidence the chronological succession and the geographic distribution of species—is still an important legacy. The Ameghinos wrote a natural history of the country by perforating its ground. They were crusaders of science, of the nation, and—in a certain sense— of capital.

The brothers’ archive is one of the most important holdings of the Museo Bernardino Rivadavia, founded in 1812, just two years after the May Revolution that set off the fight for Argentine independence. Leticia dwelled on the painstaking task performed in the museum’s workshops by a pair of hands that carves rock until the vestiges of a mineralized past emerges. With those images, she edited a video presented along with a performance of the opera L`officina della resurrezione (2013) by Fabián Panisello, at the Museo Reina Sofía just over two years ago.

III

Once Leticia came upon a word that seemed to capture the intuition she had always felt. On the pages of Vilém Flusser’s “The Gesture of Writing,” she underlined in red ink the Greek word graphein. Graphein is an inscription on a surface that tears and striates, breaking up the monotony of the background to bring out the letter. For Flusser, the gesture of writing is akin to carving: it is an act of incision that disfigures the plane. For Leticia, graphein is a thread of Ariadne that obliquely binds writing and drawing, the passage of time and the experience of time, personal history and collective history. In her own terms, graphein is the breeze that reconfigures stories and alters the series of material contingencies that underlies them. She is like a scientist-artisan that bursts into a bed of remains of the past and of the future to reveal another network of connections that holds together million-year-old glyptodones, unexpected turns of events in the tale of a nation in the nineteenth-century, and the first-person experience of that same country coming undone in the early 2000s. Those links are forged in that aimless wandering that explores the surface of texts, objects, and experiences trying to get ruinous and scattered remains to speak.

Today, along with the video that gave rise to these inquiries, she has placed a series of graphic works that waver between painting and drawing. They are once again on small sheets, formats easy to transport and display. I imagine

them as the result of once again tearing those other drawings from a still fresh past. When those works are picked at, these other layers of brighter, more vivid colors surface, colors steeped in an intense chromatic atmosphere like childhood memories that muddle with dreams and hallucinations.

Feda Baeza