MICROFILMS

MARTIN SICHETTI

NOV 1. — DIC 17. 2016

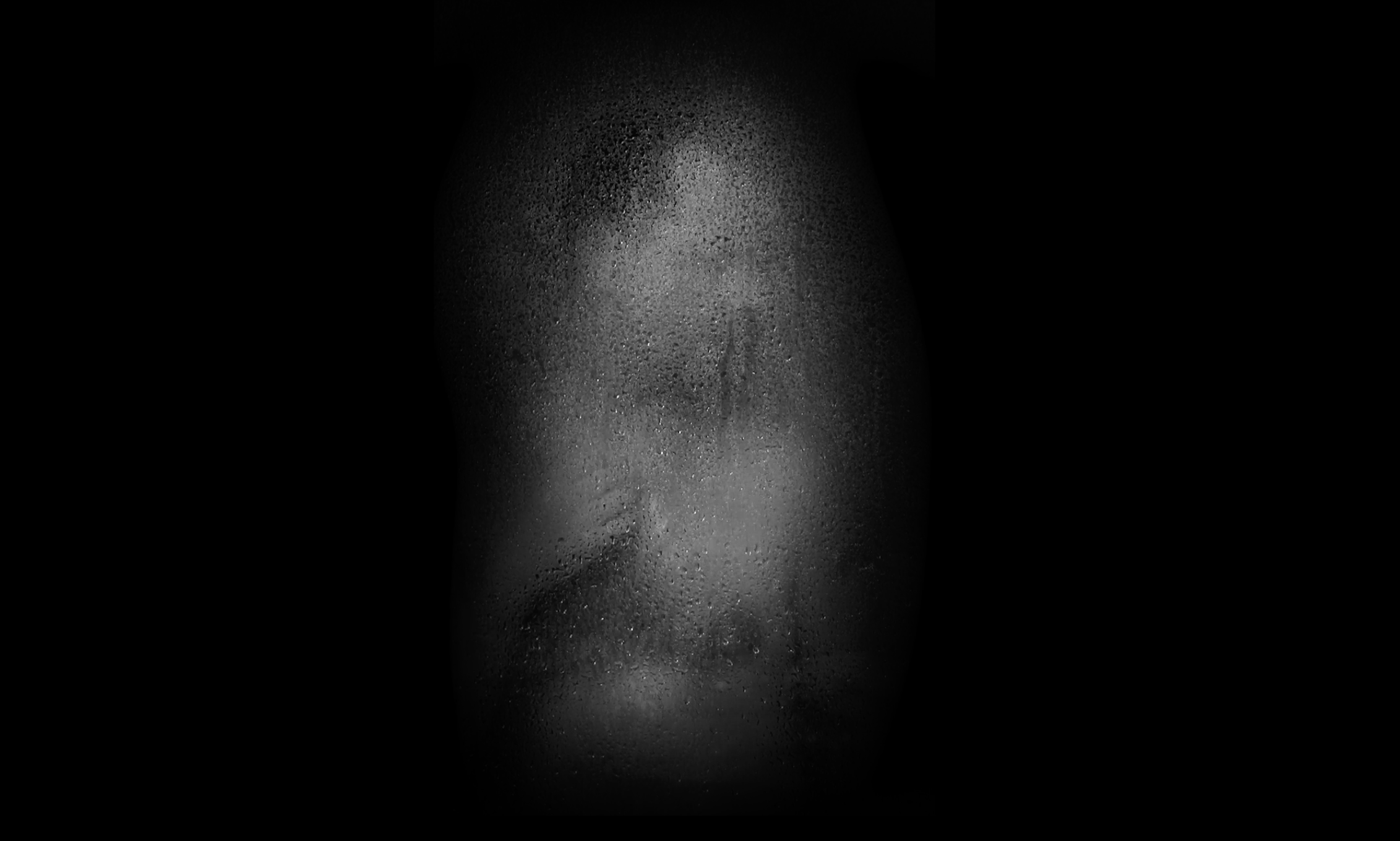

EXHIBITION VIEW

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

workS

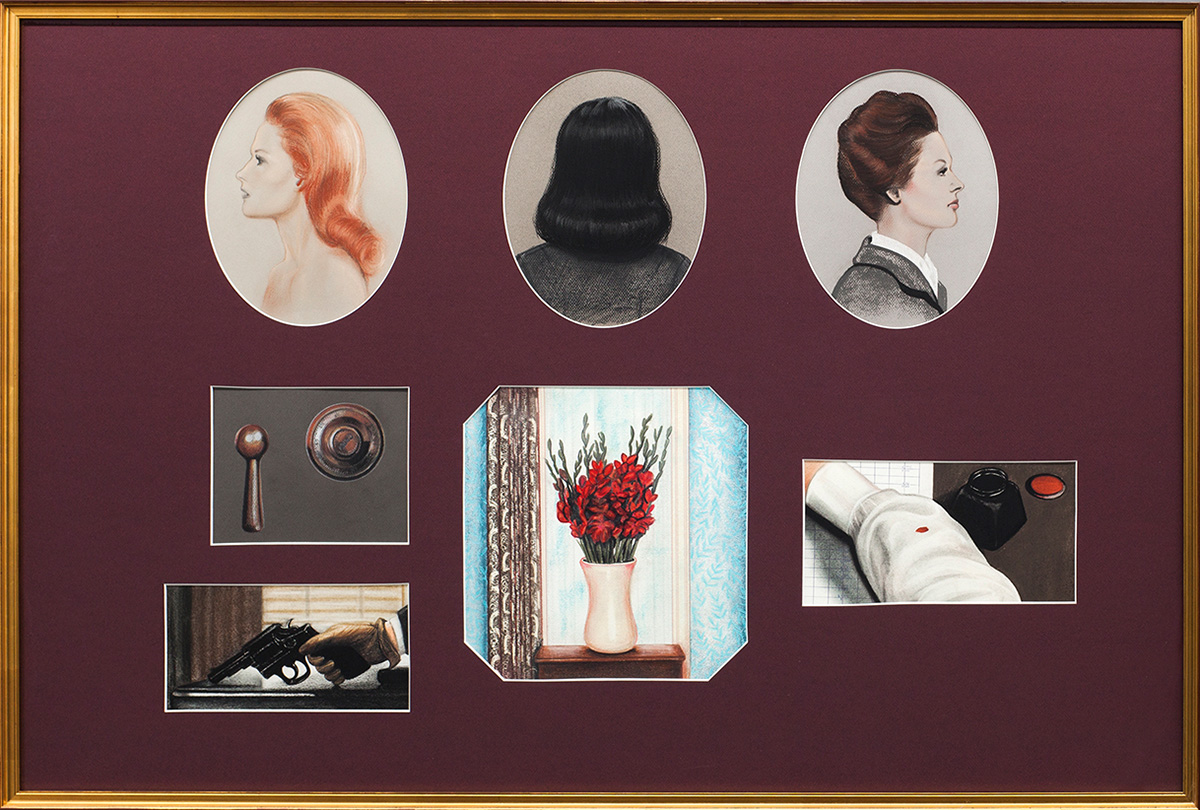

Psycho. Series Retratos de familia, 2016

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper mounted on passepartout

31.5 x 47.2 in

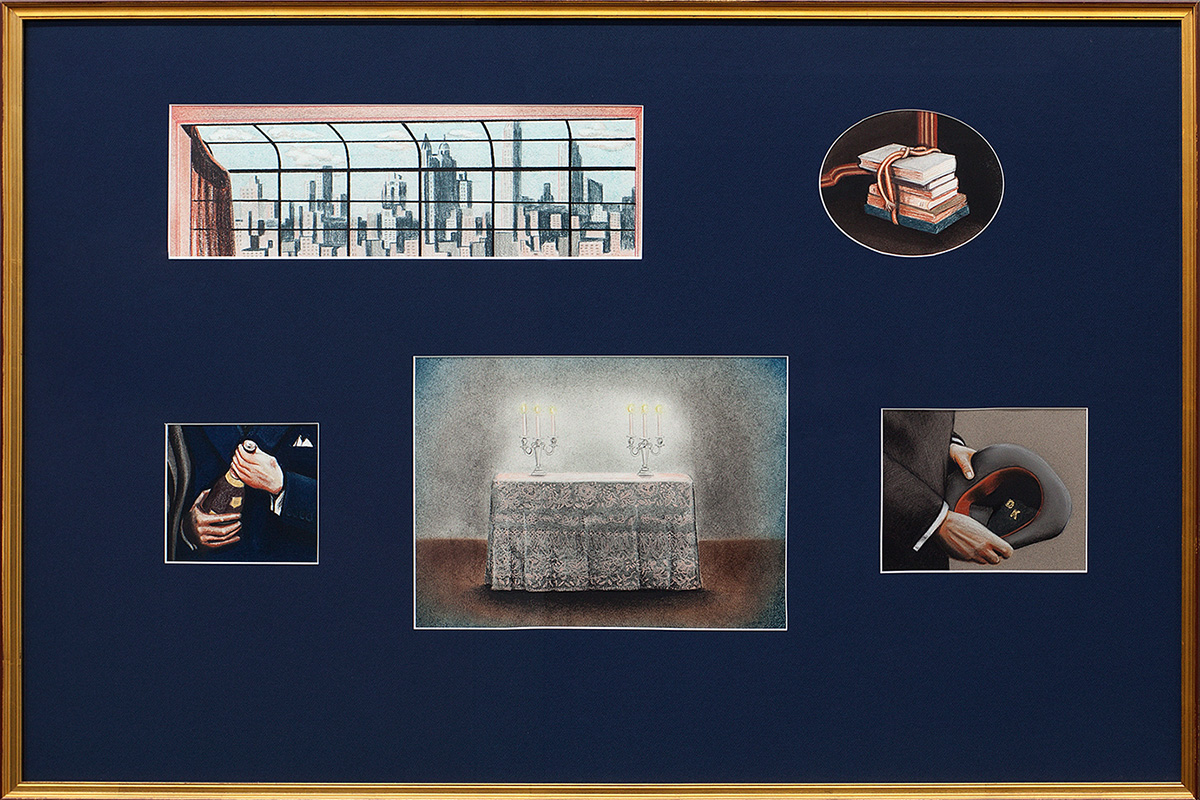

Vertigo. Series Retratos de familia, 2016

Martín Sichetti

Pencil and pastel on paper mounted on passepartout

31.5 x 47.2 in

Marnie. Series Retratos de familia, 2016

Martín Sichetti

Pencil, pastel on paper mounted on passepartout

31.5 x 47.2 in

Rope. Series Retratos de familia, 2016

Martín Sichetti

Pencil, pastel on paper mounted on passepartout

31.5 x 47.2 in

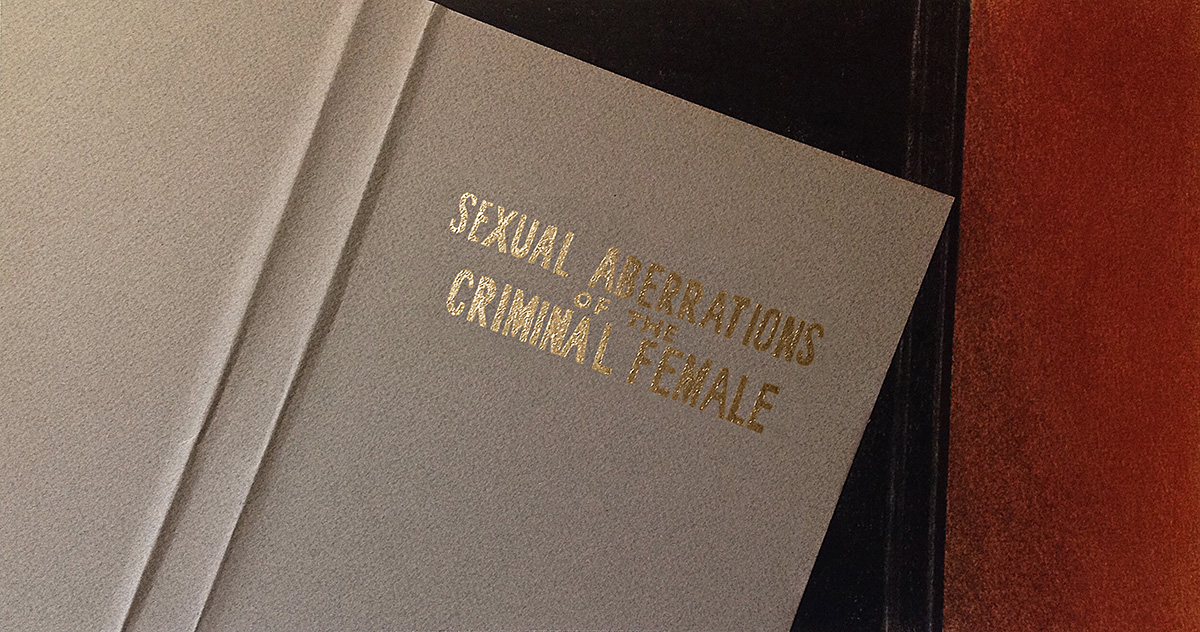

Sexual Aberrations of the Criminal Female. Series Stills, 2016

Martín Sichetti

Collage, pencil, pastel on paper with gold on paper

7.2 x 13.5 in

TEXT

ECSTASY IN SUSPENSE

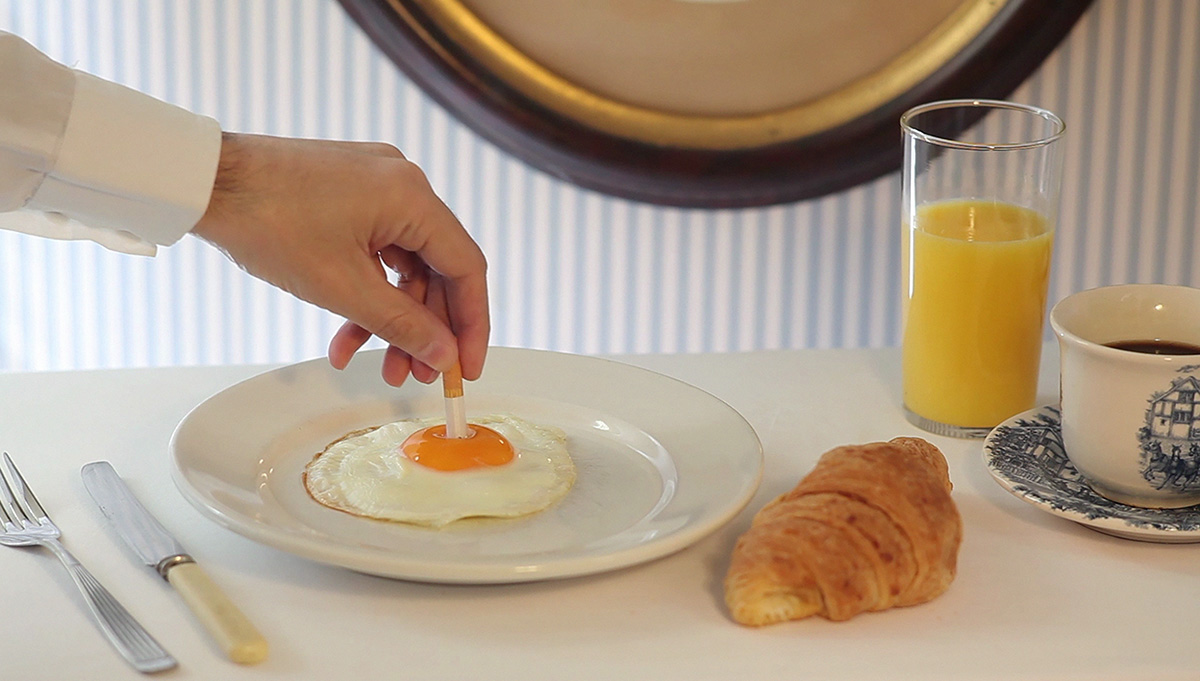

To be a voyeur in Alfred Hitchcock’s films is one of the perversions that can justify not only the History of Film but also the history of entire twentieth century. When in The Lodger (1927), the first film in which the director makes what would become his characteristic cameo, Hitchcock turns the ceiling of a house to glass so that we can spy on its tenant, the director’s eye turns into camera without limits. It pierces everything to be able to create that ideal vision that founds a strain of film at the height of the scopic drive (if you let me put it in Lacanian jargon which, according to Žižek, is the language that Hitchcock’s films speak). Like a virtuoso spy, like an ultra-fetishistic film buff, Martín Sichetti doubles that voyeuristic wager: his art is a kaleidoscope of remakes of Hitchcockian framings and objects re-projected by a microscopic spy.

The first wonder of Sichetti’s drawings and videos is the ability to capture and to magnify the visual quality of the distinctive Hitchcockian mark: each work partakes of that magnetic and deceitful elegance that takes to the extreme of nightmare, or even of hypnosis, that inclination for the dreamlike glam found in films like Dial M for Murder (1954) and Vertigo (1958). But if, as François Truffaut said, Hitchcock was the first filmmaker to really include the viewer in the cinematographic game thanks to the use of the rules of suspense, Sichetti ́s paintings place drawings like squares

on a chessboard. The playful finds its way in as optical illusion in a visual exploration where the gaze is split between reminiscence and strangeness like the eye cut by a pair of scissors that Salvador Dalí created for Spellbound (1945). Hitchcock hallucinated that fusion of psychoanalysis and surrealism with Pop-modernist clarity.

Microfilms also formulates a return to a seminal moment in the Hitchcockian sensibility, one largely forgotten by critics and historians. In his youth, the future filmmaker studied fine art at the University of London to learn how to draw. One of his first jobs was in the advertising department of an electric company, drawing ads for electrical wires. “That job,” the director recalled, “took me to film or, rather, to what film would soon become.” He offered his drawings as illustrations for captions in silent films, which is how his career in the film industry began. Later, thanks to his connection to the storyboard and to graphic thought, drawing continued to be fundamental to the art of the master of suspense, reaching its height in two nightmare scenes, the one created by Dalí mentioned above and the one drawn by John Ferren (perhaps with the help of Saul Bass, a designer of title sequences) in Vertigo. Sichetti’s serial drawings could be the dreams or hallucinations of Hitchcock’s characters or, even, the mental images of any viewer bewitched by Suspicion (1941), To Catch a Thief (1955) or Marnie (1964).

And, as if those operations were not intervention enough in Hitchcock’s world, Sichetti’s work digs the knife into the queer wound of films like Rope (1948), with its homosexual lover-killers, and Psycho (1960), with its cross-dressed schizophrenia. Though once denounced by organizations that uphold sexual diversity because of negative depictions on non-hegemonic sexualities, Hitchcock’s film, with its queer pleasure, has been vindicated in recent decades by works like Gus Van Sant’s remake of Psycho and Camille Paglia’s post-feminist essay on The Birds—and now by Sichetti’s

reframings. In the blond swirl of a hairdo, in the glistening of a blade, in the hallucinated glass of poisoned milk, or in the perfect fake window of a set, there is always a flash of glam and drag resistance. In those flashes, the invraisemblable is understood as the reverse of the identical (or of identity) and the imaginary a new trap for the voyeuristic eye. The same feat that constructs Hitchcock’s films gives Sichetti’s vision its powerful charge: turning the image into desire in a state of tension for suspended ecstasy.

Diego Trerotola