Las horas menores

SANTIAGO GARCÍA SÁENZ

curated by Santiago Villanueva

JUN 20. — JUL 29. 2017

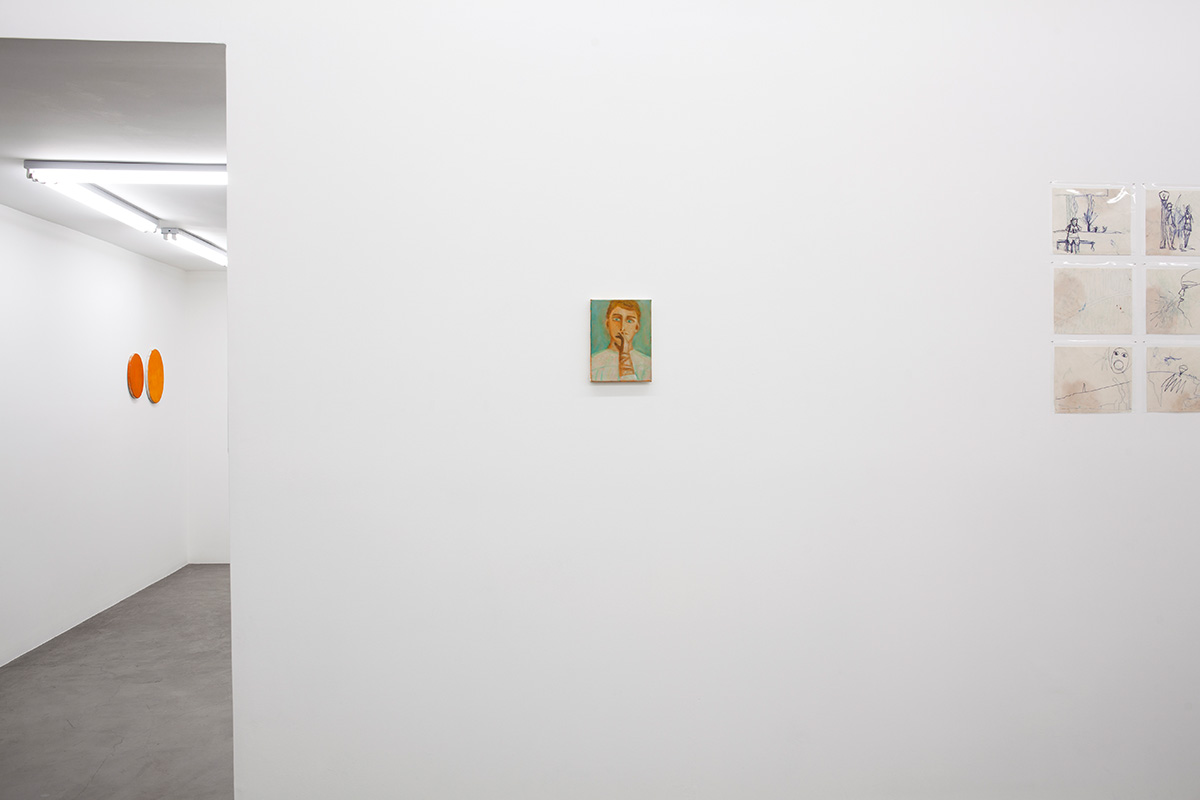

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

works

TEXTO

LAS HORAS MENORES

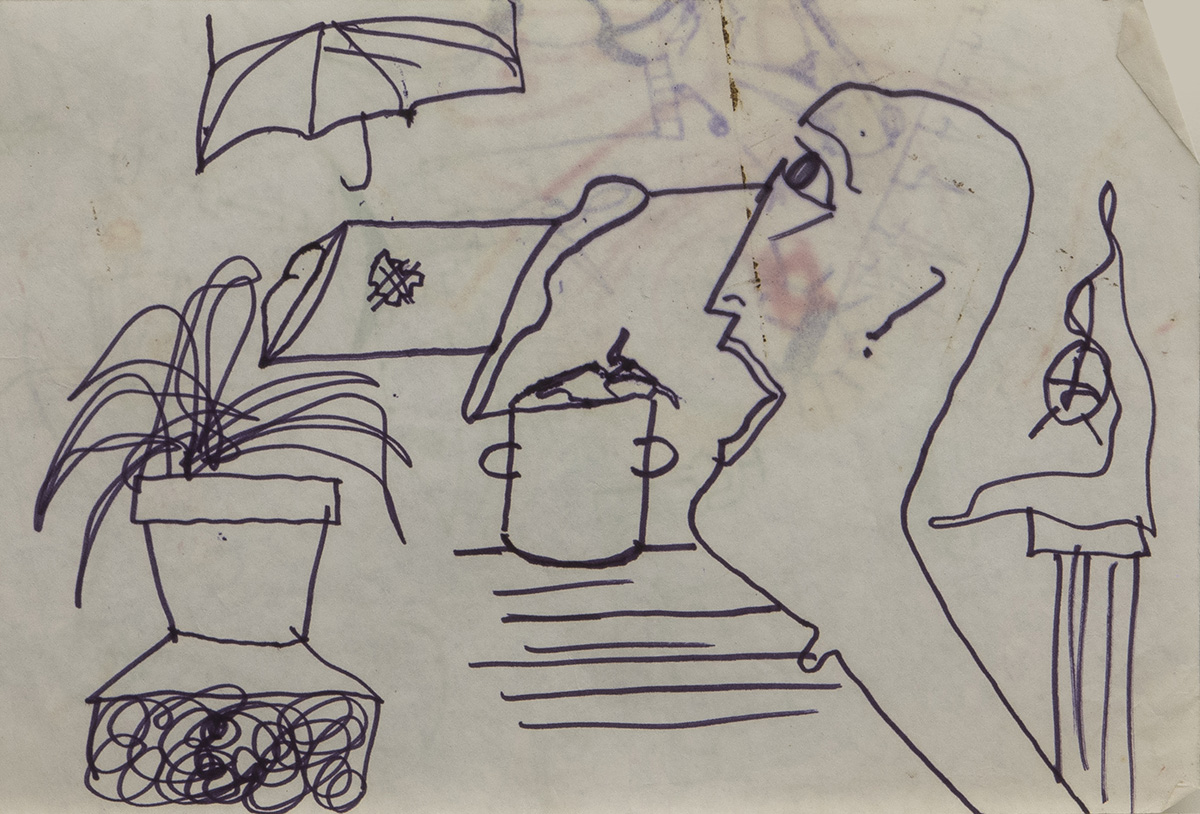

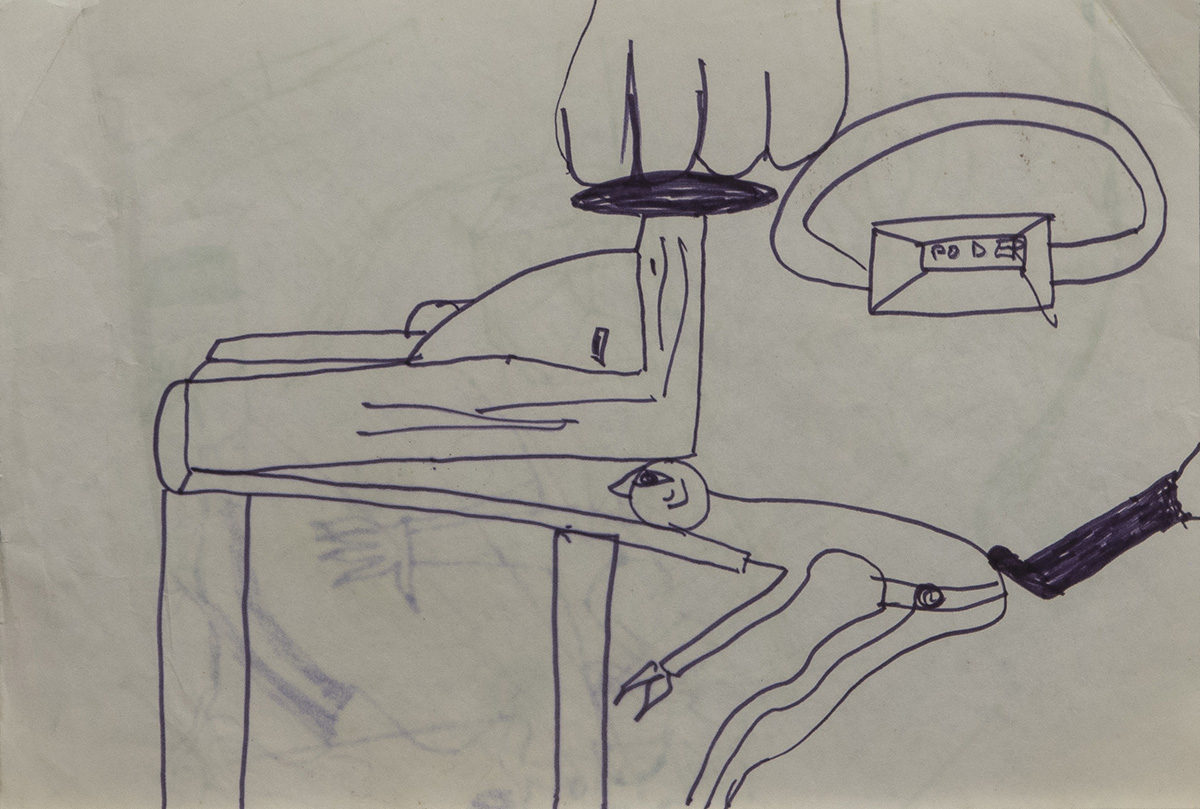

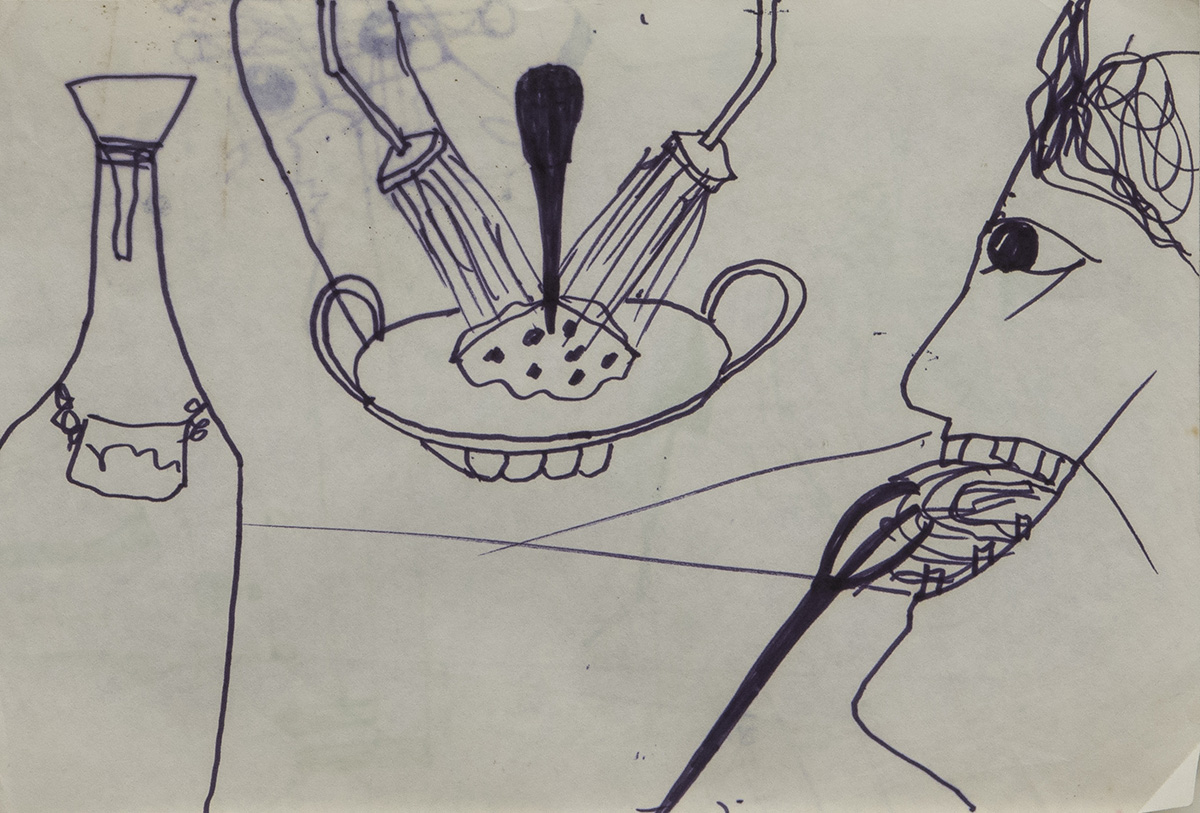

Amidst the papers, catalogues, and notebooks belonging to Santiago García Sáenz and kept by artist José Garófalo in his studio, a document describing the different hours of the day in relation to prayer, something like a wikipedia entry, appeared. The term “the minor hours” names religious prayers performed between sunrise and 3PM. During those hours, the monk need not go to church, but can stop what he is doing and engage in prayer wherever he may find himself; the level of concentration required during “the major hours,” when presence in the house of worship is mandatory, is not the same. The drawings in this exhibition can be conceived as a parallel to that moment of prayer. Produced when the artist was between the ages of nineteen and twenty-seven, the drawings are either depictions of scenes from the Middle Ages—either of torture performed during the Inquisition or of palace life—or clumsy registers of daily life with surrealist spirit.

The drawings on these sheets of paper are not responsible for what lives on; they do not hold the pain of the markings that would, with time, take hold in the artist’s painting. They see themselves as disposable, and that—in the stillness with which they come before us today in the show—means deception of their initial attitude.

Two orange surfaces—two canvases prepared for paintings that were never produced—stand out from the series. That orange that, it would appear, is nowhere to be seen in most of his production is the first layer of the artist’s paintings. It is an orange that would alter each of the colors he used and the basis for future decisions that, coupled with the drawings, build a spectrum of aspirations. The small portrait with similar background conveys a desire for silence as the gallery—like a hospital or a church—is, thanks to that unfinished painting, rife with future sentiments.

Due less to theme than to formality, a genealogical tree of the House of Bourbon is, perhaps, the work on paper that most stands out from the series as a whole. It is just a bunch of names of members of a high aristocratic pantheon. SGS, obsessed with grasping and recording the customs of an upper class, used the distance of history to poke ironic fun at his own daily life.

This is the first time that these papers, which managed not to perish in the artist’s studio, are on exhibit in a gallery. The passage of time has not been without consequence; the most unlikely transferences between the images and opportune aging process have occurred over these forty-plus years. They are in felt marker, spray works on paper, pen, or pencil; few of these drawings contain color. Many were rendered on the surfaces he used as an architecture student, others on bureaucratic and repetitive office stationary. There is none of his painting’s meditation or planning here. These drawings are not the key to understanding the artist’s later production, and that is why they require special attention.

It would seem that SGS has yet to find his place generationally: he is not a painter of the eighties or of the nineties. The eighties, today, are the years of impasto painting and the nineties of the cheap and precious object. In the eighties, SGS painted on paper and in the nineties he did narrative work. Mixing the stretch of history that it was his lot to live and age-old narratives, he decided to put his knowledge of Catholic iconography at the service of a generation in a strange syncretism of biological clock and earthly guilt.

SGS quickly sketched out his paintings in two notebooks. Dividing the page into very basic planes, he would write with loose hand in ballpoint pen the words “sky,” “city”, “learing,” “Resurrection,” “Rafael,” “thecrucified floating,” “descent,” “dark,” “people walking.” It is a sketch of a painting for the Sacred Art Biennale made with the urgency of one who knows that the final image strays widely from the initial design. These are notebooks full of the markings of someone certain of what he is doing, where doubt resides in the finished painting rather than in the brushstroke underway. The notebooks are both hints to understand how he planned his works and a threshold where his painting and these early drawings are joined. There is a premeditated and often baroque decision in the lines of the paintings whereas the notes in the notebooks are looser and sloppier. But both are gripped by the same fixation on a story.

If divided into series, there are three or four groups of work. One represents the aristocratic, courtly, and carnivalesque life of a group of persons, scenes steeped in the absurd and humor Another series—images of usually nude figures in rings or bathrooms, or sometimes wrestling—is defined by the color. A final series consists of more synthetic works in marker where more intimate, and often contradictory, situations are placed on top of one another; in them, the domestic life of a class outcast appears.

These works on paper are not sketches. Though they aim for immediate release, they are bound to micro-stories that tend to cluster regardless of temporal distance and difference in image. What binds them is a youthful sense of justice. With thin line, SGS constructs elongated characters, women walking dogs, dancers with exaggerated curves, but also a shapeless figure pissing on paintings or a dead man rising. The ways of envisioning the set, of activating its images, range from the most obvious and biased to the most personal and biographical:

– an opera in endless acts

– a comic strip for a low-budget publication

– a diary of class

– a free exercise

– reflexes

– deformations of daily life

– childhood summoned

– training in the arabesque

– alliances

– animality

– high-risk zone

– forms of community

– the mind’s eye

– simultaneity

If time coordinates are crossed, the figure of Eduardo Solá Franco appears. An Ecuadorian artist, Solá Franco was part of the aristocracy of Guayaquil. In the fifties, he put together a travel diary in watercolors. Part collection of savage tales and part series of remarks on the times, he took quick record of his daily experiences and cast a direct and descriptive eye on the male body. With a greater dose of fantasy and more muddled iconography, SGS constructed this unbound diary in which torture scenes of interrogation with historical feel intersect with parades of an ironic court life. Solá Franco and SGS both have an aristocratic background that, when idealized, projects a clown-like vision of daily life. But, in his images, SGS formulates a despotic Manechism. Scenes of torture may hint at key moments of decision on the lives of persons, but, in a displacement of the material and in the line, they provide us with a glimpse of a pleasure bound to an intimate release with no outside visions. They are, inevitably, the sadomasochist practices that run through the gay imaginary of a young man who, during the eighties, fled to his most extreme thoughts on a sheet of paper. In later decades, that attitude would shine through in the paintings that set out an endless Way of the Cross that goes beyond the classic religious tale to adapt to a personal story.

Santiago Villanueva