REPÚBLICA, LIBERTAD Y CONSUMO

PATRICIO LARRAMBEBERE & EDUARDO MOLINARI

CURATED BY ALFREDO ARACIL

JUN 18. — AUG 3. 2019

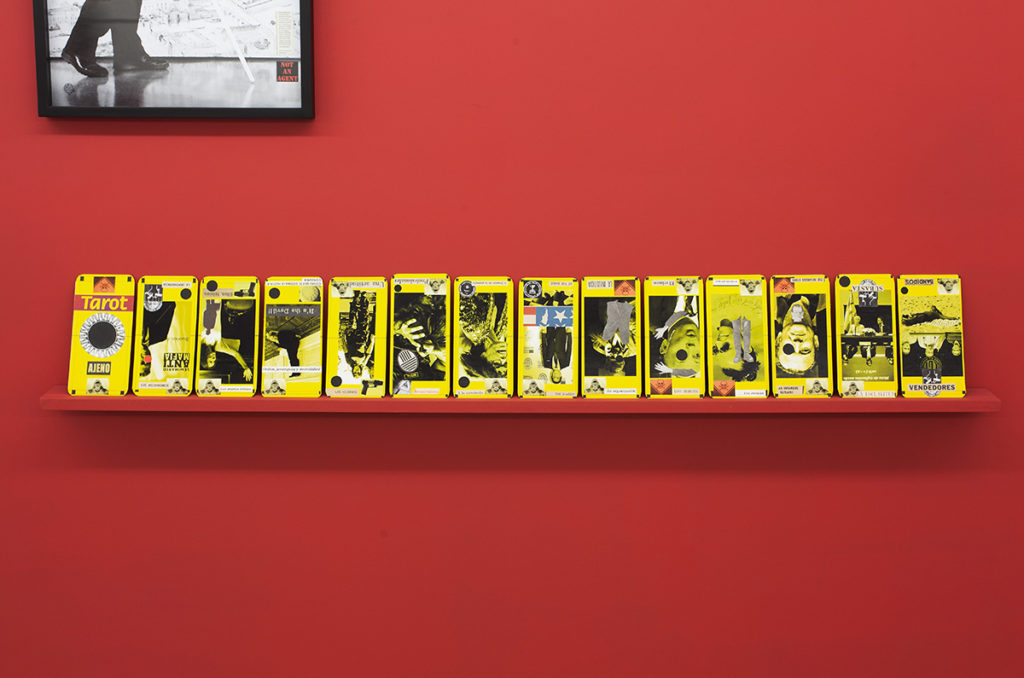

exhibition view

Ph. Ignacio Iasparra

works

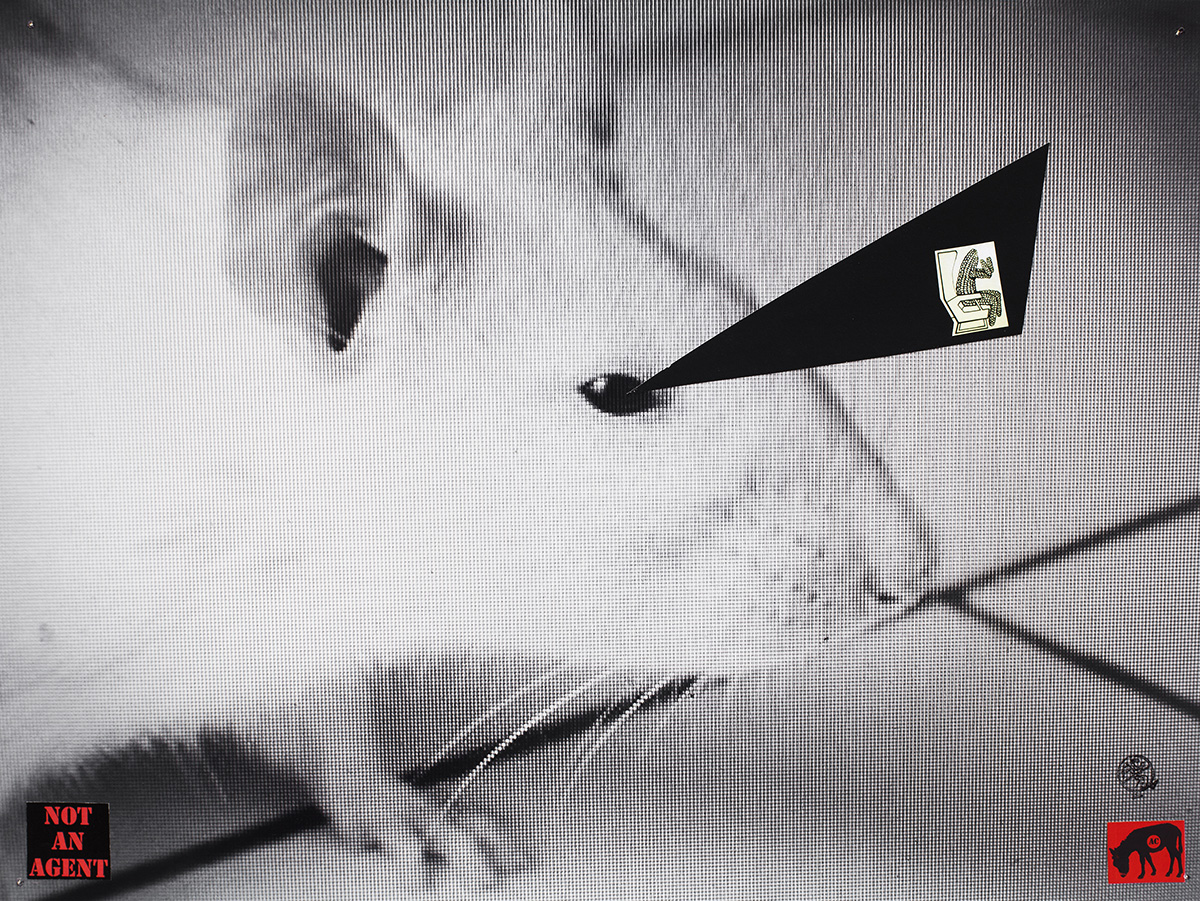

El historiador ciego. Series Kosmovisiones, 2019

Eduardo Molinari

Intervened photography

23.6 x 15.3 in

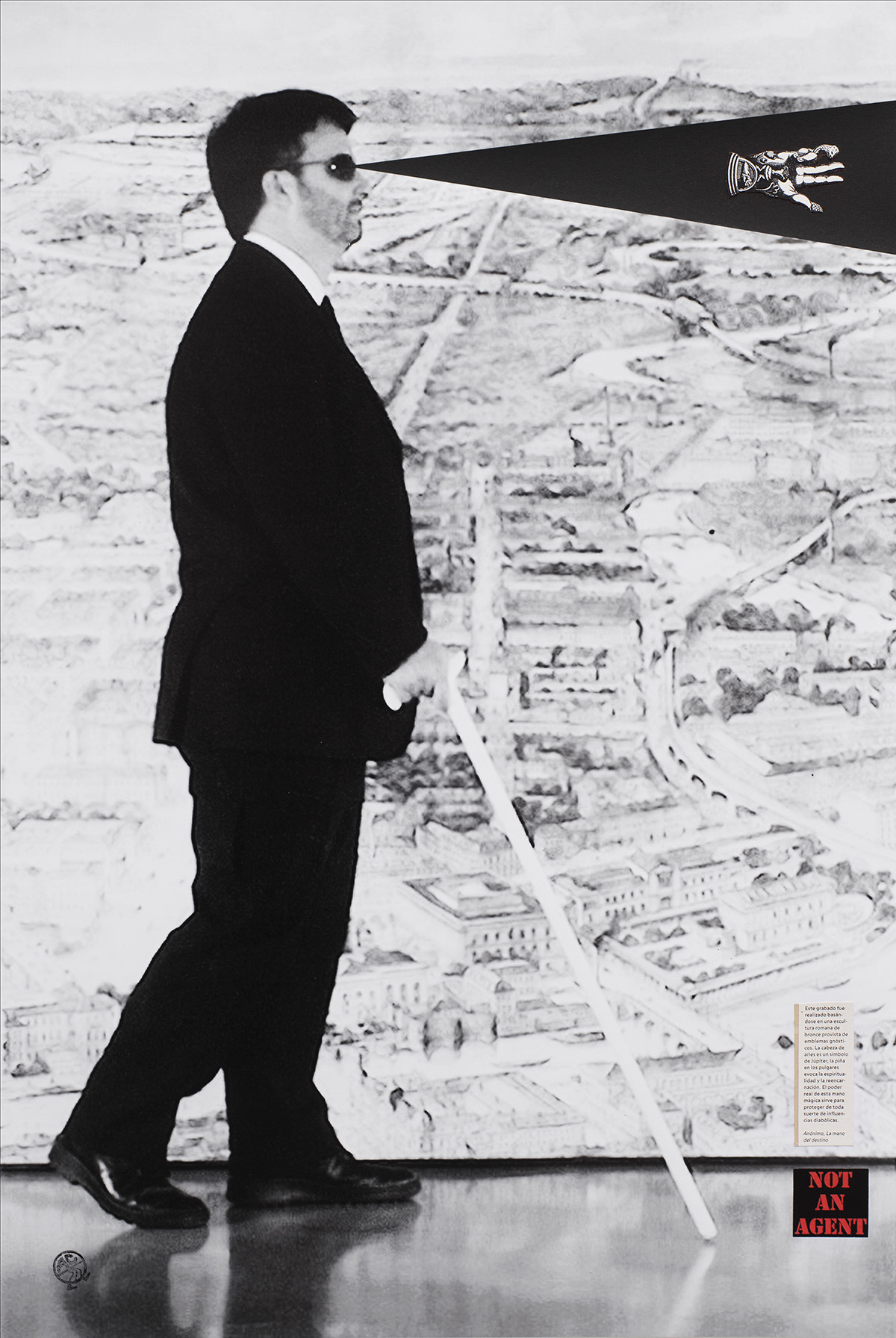

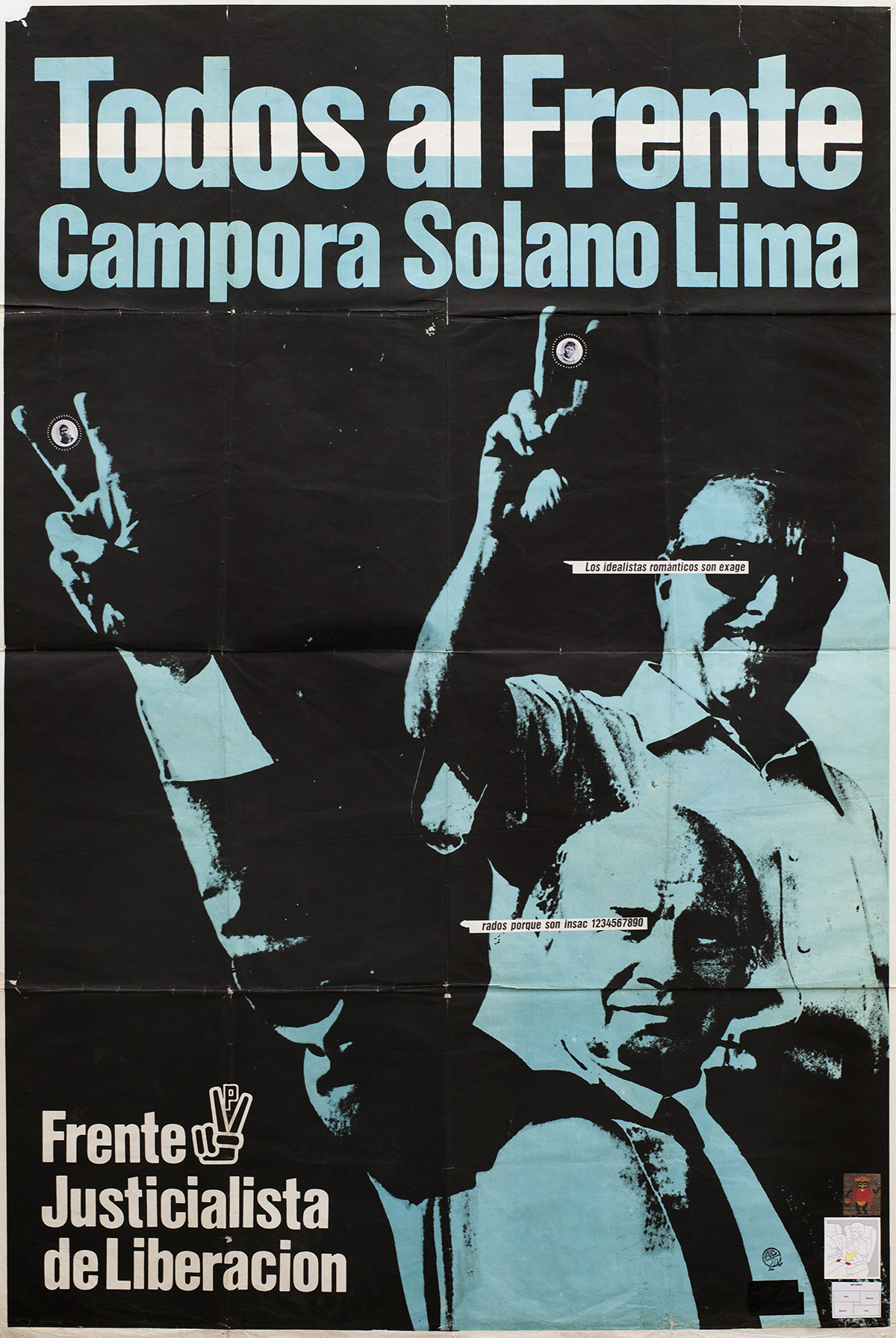

Idealistas insaciables. Series Kosmovisiones, 2002

Eduardo Molinari

Original poster intervened

42.1 x 28.7 in

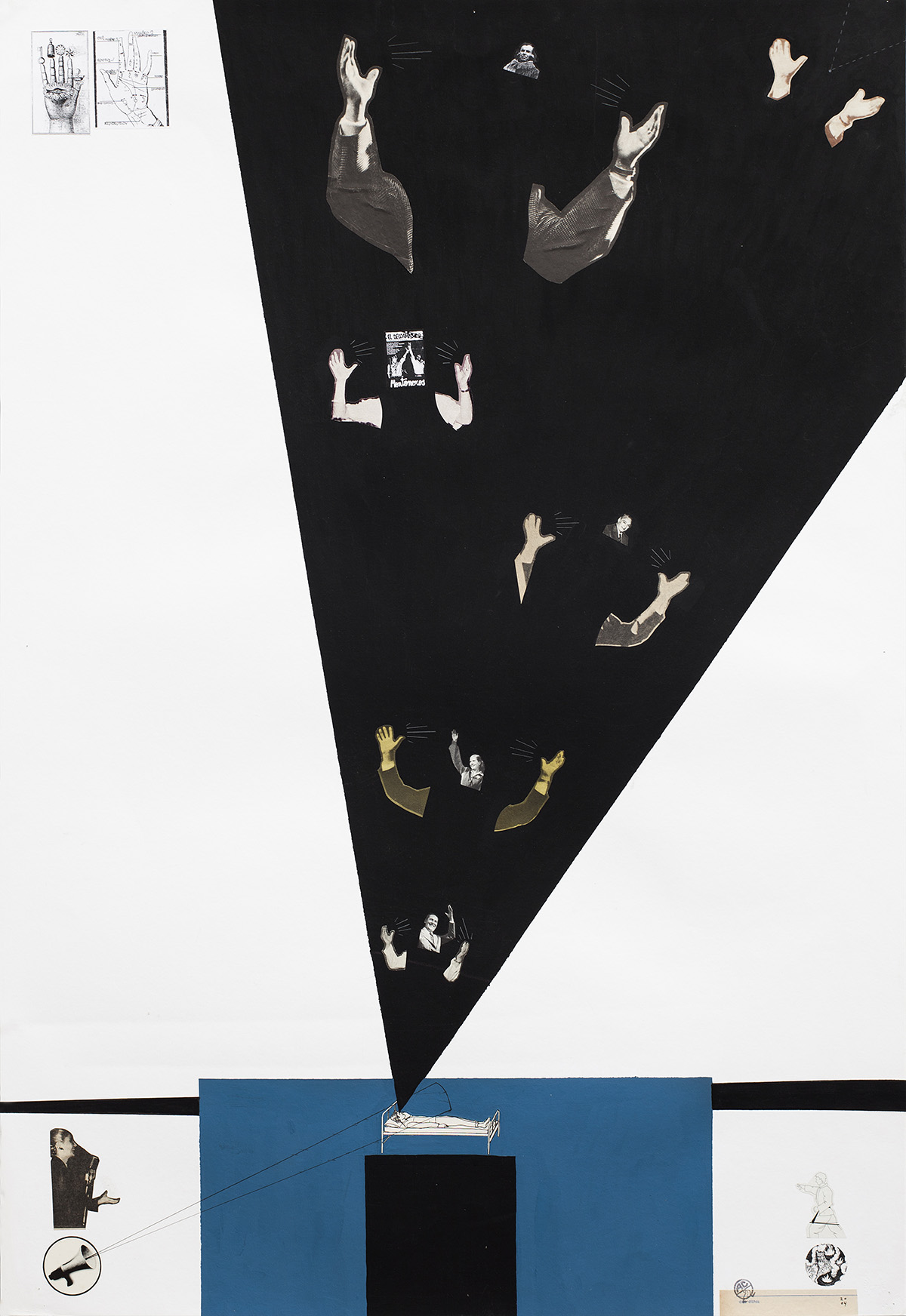

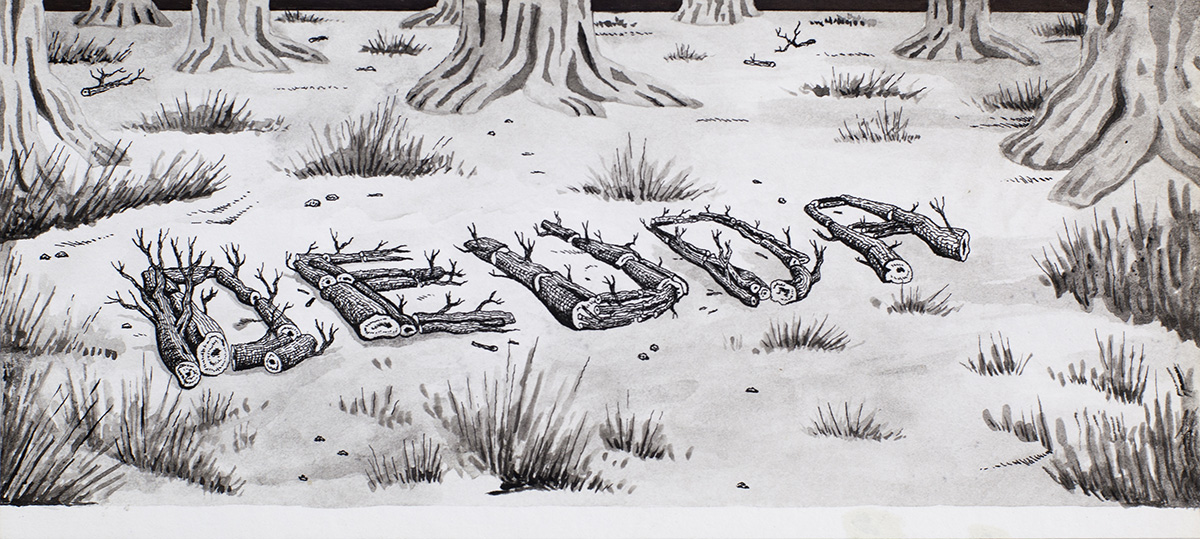

In absentia. Series Geoeconomía, 2005

Eduardo Molinari

Ink and acrylic on paper

4.3 x 9.1 in

Ni nostalgia ni pasado mejor. Series Memorabilia AC, 2015

Eduardo Molinari

Chrome medal

1.4 x 4.1 x 5.9 in

Edition 1 of 3

El grillo de las Pampas en km 12, 2019

Patricio Larrambebere

Acrylic on canvas and 3 glazed ceramic pieces

23.6 x 23.6 in & variable dimensions

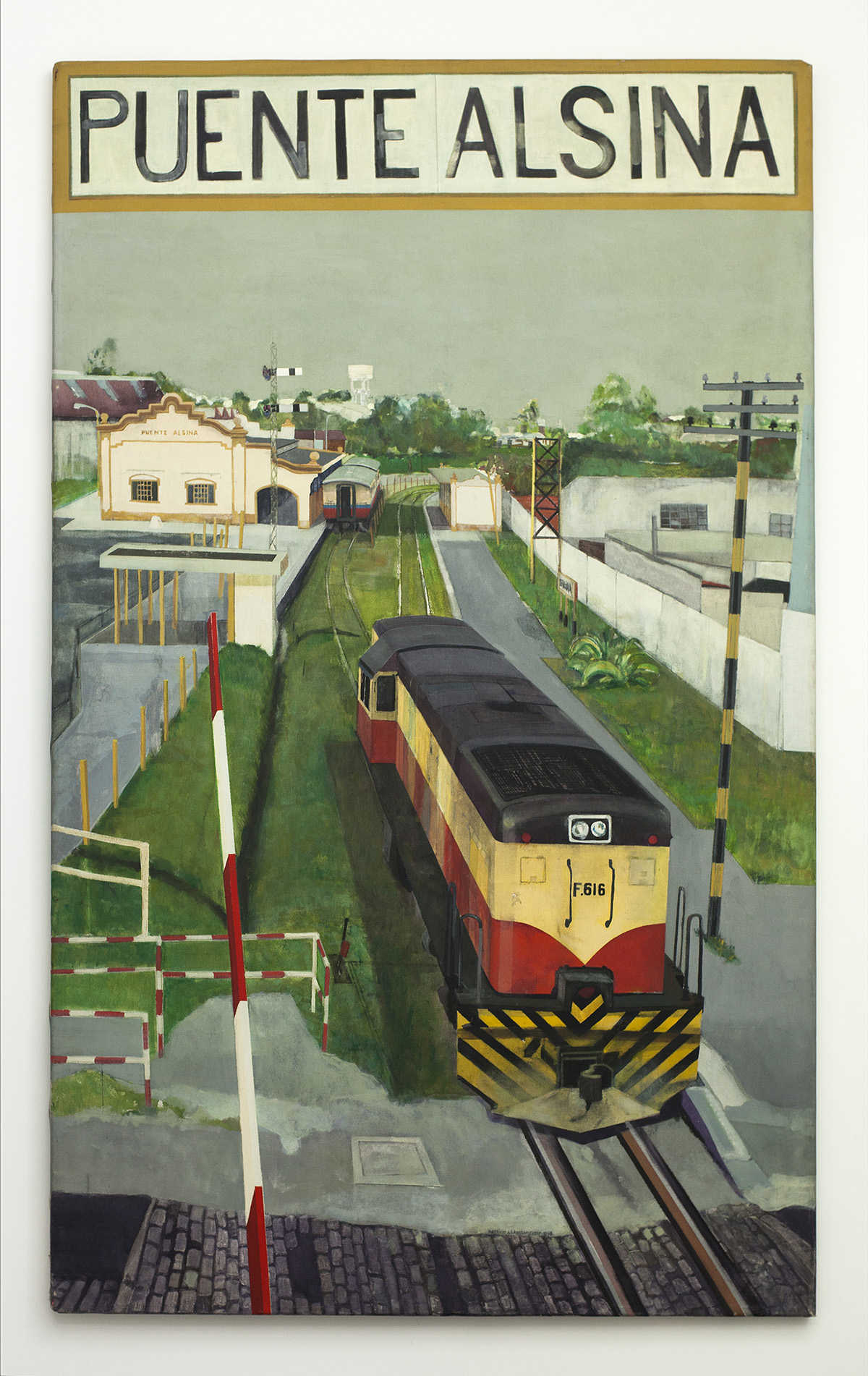

Libertad (FCMdBA), 2019

Patricio Larrambebere

Acrylic on canvas and 3 glazed ceramic pieces

23.6 x 23.6 in & variable dimensions

República, Libertad y Consumo, 2019

Patricio Larrambebere y Eduardo Molinari

Digital sublimation on advertising banner fabric

55.9 x 34.2 in each (four flags)

Edition 1 of 3

text

“The function of the discourse is not in fact

to create “fear, shame, envy, and impression,” etc.

but to conceive the inconceivable,

i.e. to leave nothing outside the words and to concede nothing ineffable to the world

Roland Barthes: Sade, Fourier, Loyola

“…Meet me on the wastelands…

…amongst the smoldering embers of yesterday…”

The Jam, Wasteland

Joining the irreconcilable, singling out and projecting past shadows onto present conflicts. Summoning ghosts, unsettling presences, no faster than clay dries, when forms of government seem to get inspiration from witchcraft and science fiction. Drawing magic circles to not surrender to commonsense. Socialize discomfort, from the margins and with a network of allies. For over two decades, Eduardo Molinari and Patricio Larrambebere have been sharing concerns and cares in spaces like the Taller Proyectual Pintura at the Universidad Nacional de las Artes, a research workshop where the exchange of knowledge and practice is envisioned as one of art’s tools. And, since the mid-nineties—the alternative nineties—they have held joint shows like Quintaesencia (Centro Cultural Recoleta, 1996) and Manifiesto Cimarrón (Biblioteca Miguel Cané, 1999). Those projects navigated the limits of what an exhibition is, conjugating the same approach in different media: artistic practice as stance and public engagement—always with a biting, and never cynical, critical sensibility, trying to join collective and personal memory, to get at the ordinary misery hidden in the headlines, the experience that, because so close, is blinding, baffling beyond remark.

More circumstantial than anthological or retrospective, República, Libertad y Consumo hopes to open debate on ways of inheriting and the ability of some images to live on, to become inheritance. Neither anachronism nor rupture. Like the RLC circuits1 we once drew in forgotten physics classes, we have drawn a vicious circle in the HACHE gallery. Spinning

round and round inside the maelstrom, round and round the uncertainty we feel, round and round our very selves, in a journey through stations that form scenes or life lines that thwart the overall circulation of floating images with which governments would control subjectivity, affixing the past in the present and making it almost impossible to imagine a

better future.

If we accept that words do things, that they produce reality, it is not ludicrous to say that Republic, Freedom, and Consumerism could be the ingredients of a secret potion or a designer drug. Depending on the formula, the combo does not always lead to sorrow or submission. Three words that are often empty signifiers. Almost an oxymoron. The show includes another word as well—the word Health—on a flag and in a number of intervened photographs. Flags and slogans that form part of a spell that deadens the world and disaffects. The poison that paralyzes and extracts vital energy from bodies and territories. But flags of a pharmaceutical power, of a possible healing. Like El Historiador ciego (The Blind Historian) who explores Eduardo Molinari’s El Archivo Caminante (The Walking Archive). El Historiador Ciego is potentially sighted—he opens doors—but also the agent of oppressive thinking. He doesn’t see what it is not in his interest to see. He is bewildered by blinding lights. Depending on who waves the flags and how, the forces unleashed by that RLC sequence might head in another direction. It is not for nothing that unexpected breezes

blow, that shades and lights appear in the dark. There are still those who know the gualichos that ward off danger. Effect and counter-effect: now seizure, now resistance. Draw and erase the boundaries between the possible and the impossible. And, ultimately, decide who lives and who dies. “Disconnect to reconnect differently.”2 In other words, analyze how the monetary and libidinal flows that circulate around Argentina are inscribed and capitalized—that will provide us with a handbook on how to deal with domination.

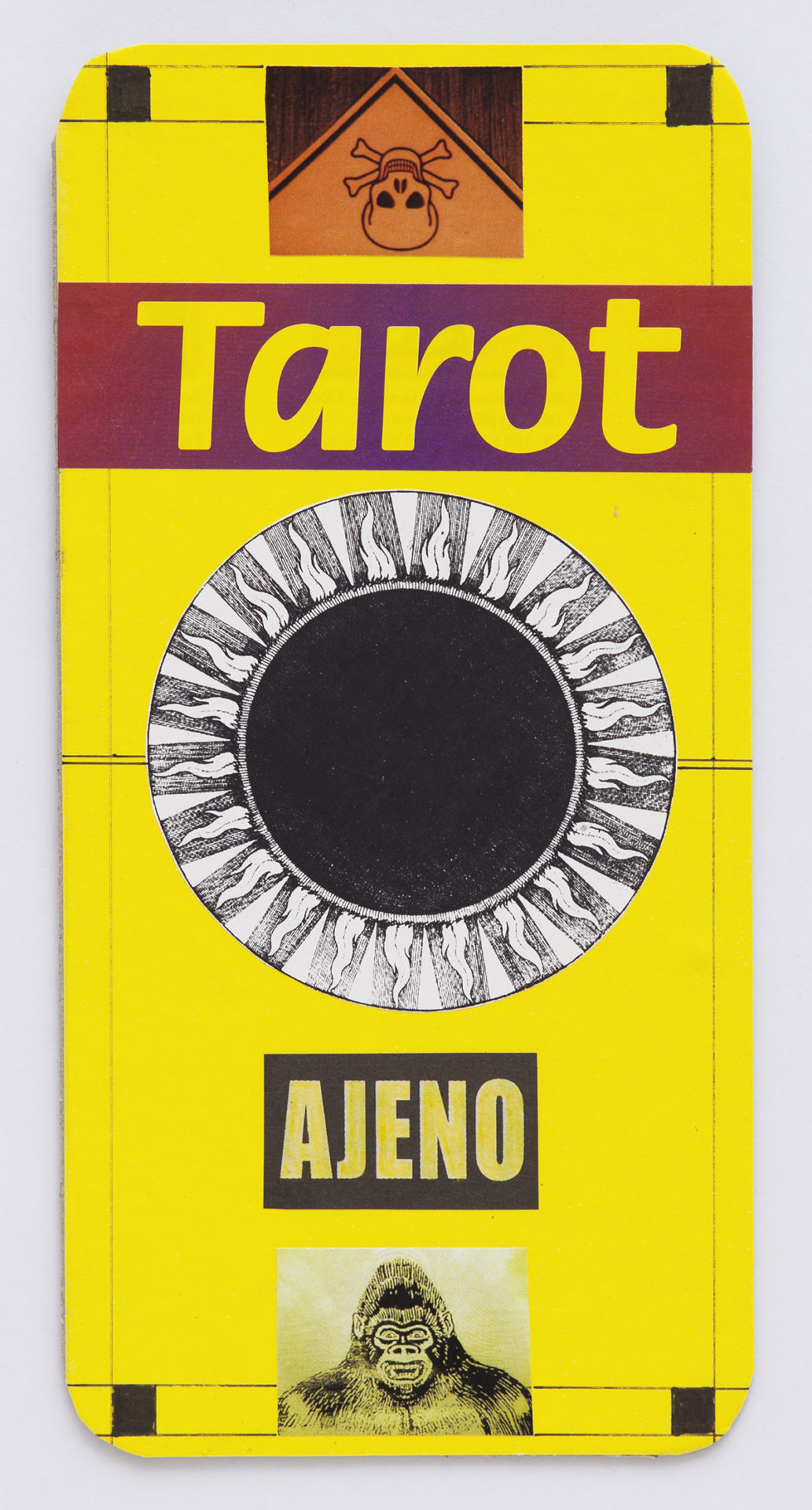

With Election Day impending, we look to opportunism for a strategy, a way to act on that which it is still possible to transform. At stake is a not meaningless polemic—not at all—but bearing in mind how, for Eduardo Molinari and Patricio Larrambebere, politics, like art, is a call to embodied practice rather than to stop doing/making. República, Libertad y Consumo is a far-reaching game where the threat of the end of the world and violence are not only symbolic. Joining that “doing/making” to practical notions of “knowing” and “producing,” the show presents an archive of images taken from the world of consumerism, of product design, of commerce, of transport, and of domestic industry—the nation’s material basis, its living culture, from the nineteen-thirties through the most recent left-leaning populist government. Those images are juxtaposed and combined with a series of figures of animals and magical symbols (the hare, the man of corn, the toucan) of very different inspiration and origin, and with photographs and illustrations that make up a Tarot deck of episodes and shady characters in current events. Eduardo Molinari’s Tarot Ajeno (Others Tarot) includes images of a team of experts in black magic and war technologies.

The artists stir together present, past, and future—barely disguised in this broth of images and sensations that does not distinguish between the literal and the allegorical. In this magic cauldron are images of history, a history of images. Images that are memory and, hopefully, future. At stake is testing out, as Martínez Estrada once did, if there is in fact

something immutable or essential. “The knife dives right in because it is not garment, but flesh itself, it partakes of man not of attire.”3 With Martínez Estrada—with the great heterodox, uncomfortable for everyone, but especially for his peers—Patricio and Eduardo share the bitterness of pessimism grounded in analytical method. And in an aesthetic, a

landscape somewhat surreal and somewhat metaphysical. Remember that in the late fifties Andre Breton played the part of the clairvoyant: “the malaise or sickness that besets the world of the twenties is different from today’s. The spirit, then, was threatened with paralysis, with getting stuck; tomorrow the threat will be dissolution.”4 Breton also said that at a certain point surrealism had ceased to serve a revolutionary drive and liberating flows to serve instead capitalism, the machinery that produces overly appealing images that promise freedom and bring submission. On the walls of HACHE, this passage from utopia to dystopia is naturalized by guns and police dogs that are and are not characters in a tale, by vultures that may not fly but are still capable of inflicting social and economic harm, and by teleprompters with empty words, the speeches of a president who would rather not have to give explanations. We also have—it’s true—Edmondson train tickets, though at this rate there’ll be no passengers left (emigration times are here once again). Souvenirs of progress that ends in head-on collision, but a hygienic one—no one injured and no material damage. Remarkable. When relentless modernization is a synonym for rationalization. When the choice of progress brings only destruction.

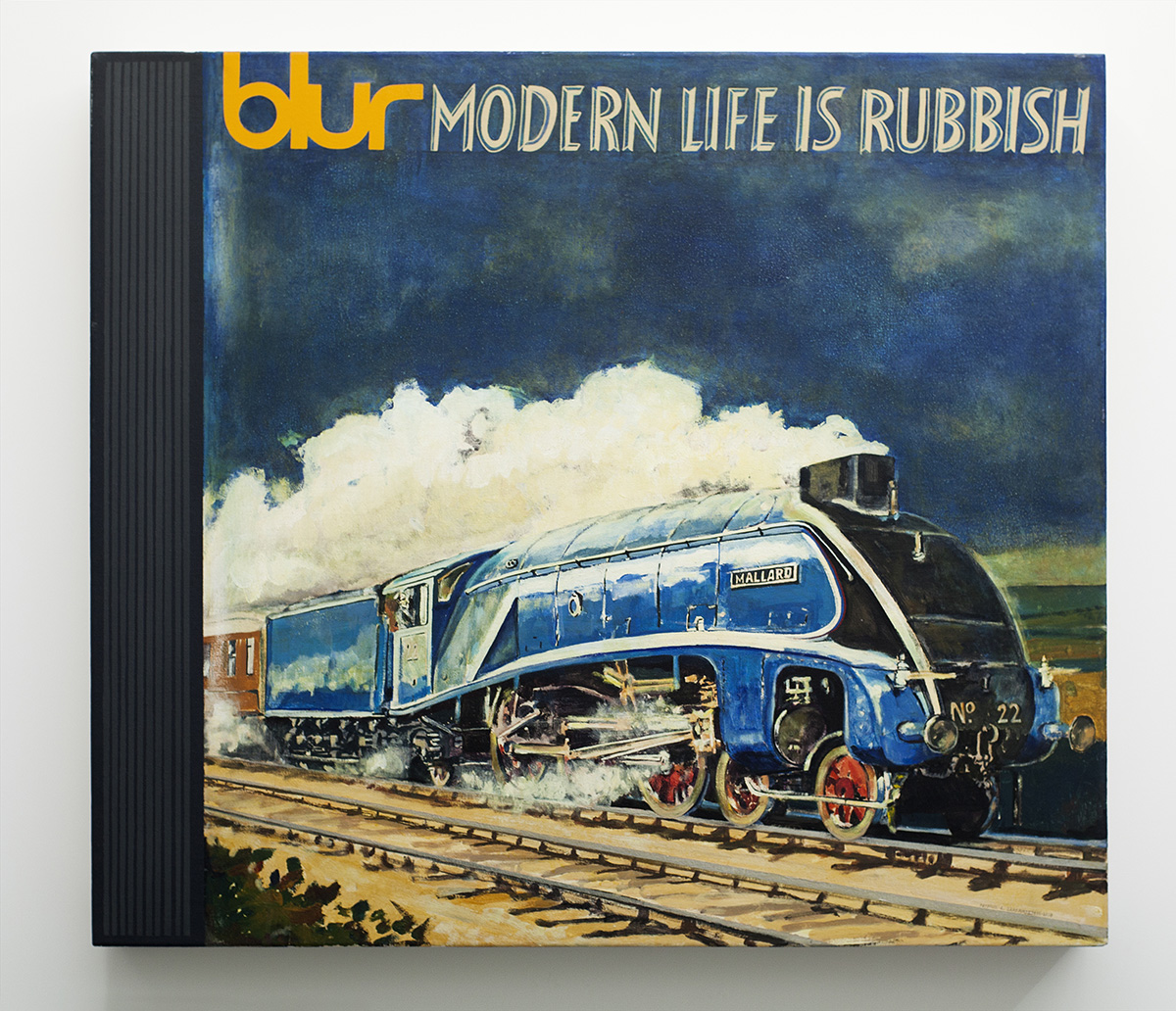

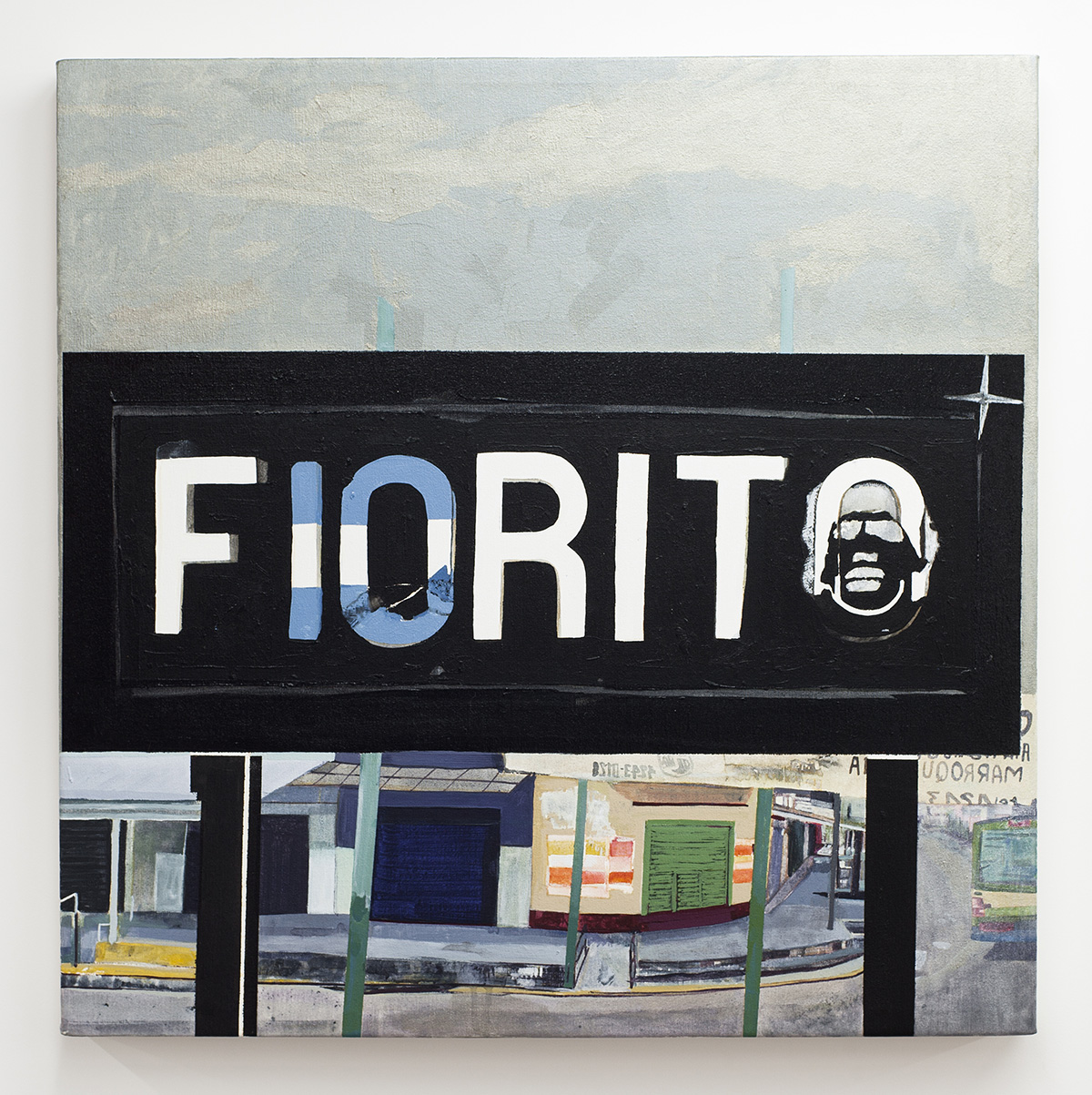

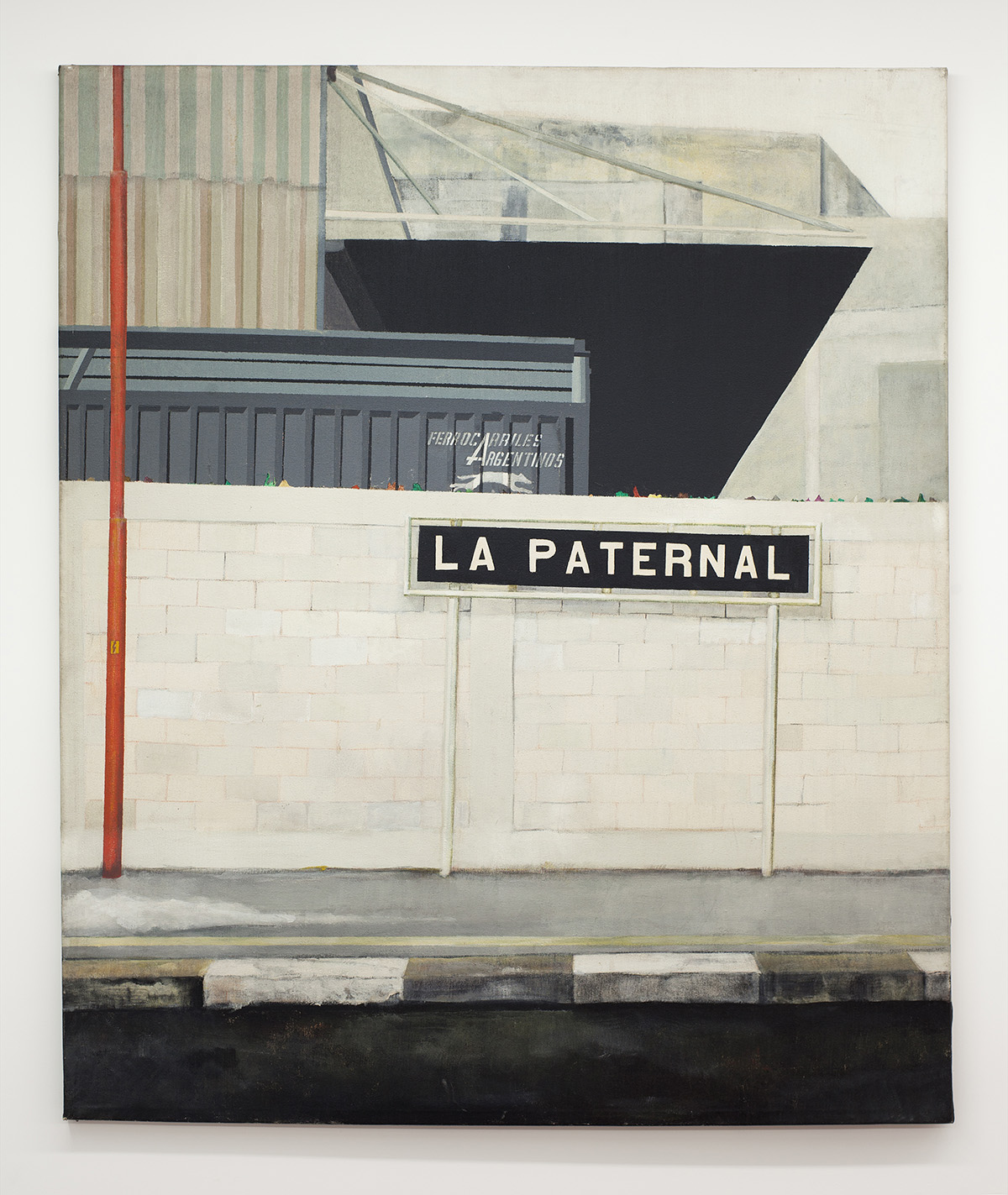

This ocean of contested images is like background noise, like a mantra splattered with slights—they’ll be payback, we hope, someday. First we have to learn how to defend ourselves, tracing other possible connections, joining images with no set intention, images in motion—life lines that we hope help us to keep our grip. To pull up the hand brake and clasp onto what we don’t intend to lose. Who would choose nostalgia over wrath? Take, for example, Larrambebere’s new paintings. As he explains, “The old Buenos Aires Midland train line that went through the dairy region of southwestern Buenos Aires province. It was pulled up by Martínez de Hoz during the military dictatorship, abandoned and even insulted by recent decrees in keeping with the capitalist realism model. It is now reduced to a bare minimum. A cloud of doubts (maybe just so much smoke) has surrounded its possible refurbishing since August 4, 2017. Today, apathy and glyphosate have turned it into five-hundred-kilometer-long-by-fourteen-meter-wide wasteland where the only things out

grazing are affliction and genetically modified soybeans.

Any inheritance, carcinogenic or not, is, in the end, a technical problem. As Isabelle Stengers and Philippe Pignarre suggest in Capitalist Sorcery, we must adopt strategies where what appears to be abandoned is re-appropriated collectively. That is why it is essential, in our view, to rethink what our collective heritage is and how to defend it, with no aestheticism or duplicity, reflecting on what is possible and what will be passed down to us in a horizon of debt and hopelessness, a scene where nothing belongs to us.

The show brings together works from different periods and in different formats, materials, and techniques—collage, intervened photography, drawing, painting, poster, and the occasional object. What do they have in common beyond the phantasmagoric return we propose? Like Larrambebere’s blue-process prints or cyanotypes—a photographic technique

where images are developed entirely by exposure to sunlight—all the procedures used share an inclination for and engagement with the analog, an insistence on time, on repetition. Démodé techniques and operations that, for that very reason, trace a number of genealogies. There is, of course, Molinari and Larrambebere’s sentimental tie to the aesthetic of the document and the universe of seventies activism. But we’re not going to go over Tucumán Arde again. Because, on the other hand, we have the Molinari and Larrambebere committed to the study of a certain local tradition that turned art and life into an anti-elite project, a practice open to trade between avant-garde art, popular culture, and craft. Indeed, for Molinari and Larrambebere, that technical question is a knowledge and a praxis situated in a territory and a history, a subtlety and attention beyond the introspective. A minor art that they probe, stratify, and thicken.

Passed down to them from the Artistas del Pueblo and the Sociedad Nacional de Pintores y Escultores, with its Salón de Independientes, is concern with art’s social function and the choice of realist forms as means to protest more and more glaring poverty and wretchedness, not only on the outskirts of the city. From them they also get “a form of production that privileges humble or disregarded techniques and materials, defending—in that use—art as manual skill and creator as worker.”5 The artisanal work of the artist-worker in the techniques of mechanical reproduction invented by modernity: a strategy that has a mobilizing effect. We also have the influence—not only formal—of painters from the seventies like Juan Pablo Renzi and Pablo Suárez, with whom Patricio Larrambebere studied. That influence is felt, mostly, in a poetic use of the literal, evident in how the human figure appears and vanishes, in deserted places that portend a way of life in extinction. But let’s not hasten away from the artist’s craft and work, from a knowledge-praxis and a time spent, a workday, once the basis for the demand for a decent wage and a politics of solidarity. A perfect way into the preferred debate in Argentine art at the moment: professionalization. Molinari and Larrambebere experienced that debate in the late eighties and early nineties, when they were finishing up art school. The period of privatizations and mass layoffs from publicly owned companies. Before the 2000s and the art that, it would seem, “never was.”6 When everything was lovely and innocent, when art was made in and for a circle of friends. Before the precarious art scene we know and love today had, some authors tell us, “turned into a professionally organized system of institutions and galleries.”7 All that happened—by the way—when Eduardo and Patricio began teaching at the public university. And when a number of selfrun art collectives were forming like Grupo de Arte Callejero, Grupo Etcétera, the Internacional Errorista, as well as the Edmondson train ticket group founded by Larrambebere in the late nineties.

Coda

But let’s get back to the show. There are still some unanswered questions, chief among them to what extent the words in the project’s title are redeemable. Is there anything worth salvaging in the Republic- Freedom-Consumerism sequence? Is a non-neoliberal form of consumerism possible? Is there freedom outside the market? These questions are open to debate. First off, it’s strange how the face of the interlocutor contorts when these questions are asked over the course of a conversation. The Republic-Freedom-Consumerism sequence is somewhat incongruent and somewhat wicked. A mirror where everyone sees themselves, but whose frightful reflection no one wants to acknowledge. Therein lies its power. These are not sterile or innocent words. They can still arouse passions.

In Going Overground: Post-Punk between Populism and Popular Modernism, cultural critic Mark Fisher pulled a polemic move—all the more so if it is applied to the Argentine context, where the popular means things it does not mean in the United Kingdom, that is, where it is not so clear that a popular culture is possible at the margin of what has been theorized and practiced as populism. Notwithstanding, his hypothesis merits debate: some art and, more broadly, the youth culture spread by the mass media (press, radio, TV…), mainly from the fifties to the late seventies—at which point a conservative counter-offensive was waged—dared to name its ghosts. It tried to channel many of the feelings repressed, to turn them into alternative lifestyles and liberation practices at odd with social institutions and reigning morality. It set out, then, to turn class frustration into personal and community theories that did not manage to go beyond the tight confines of the bourgeois world critiqued. That lead, Fisher thinks, to a sort of latent revolution, a revolution to come, held within promises and outside of time, virtual promises and possible experiences never consummated. Or maybe

they were, but our exotic vision of the past—a vision that is in fact pragmatic and fetishistic—cannot tell the difference between the actual and the plausible.

Molinari and Larrambebere seem to take Fisher seriously: once again, what they do is problematize and politicize processes of inheritance, in other words, how to assemble ourselves from that which no longer belongs to us. “Confronting the process of watching the taken for granted become the (retrospectively) impossible. The way to avoid nostalgia is to look for the lost possibilities in any era.”8 In other words, revel in the thousand defeats yet to come, without getting dazed when power is served on a platter.

1 In electrodynamics, an RLC circuit is a linear circuit with an electronic resistor, an inductor, and a capacitor. The interconnection between those three components determines the type of RLC circuit—serial or parallel. The behavior of an RLC circuit is generally described by a second-order differential equation, where RC or RL circuits act as first-order circuits. With the help of a signal generator, the circuit can be injected with oscillations and, in some cases, the phenomenon of resonance, characterized by an increase in the current, is observed: the entry signal chosen corresponds to the pulsation of the circuit itself, which can be calculated using the differential equation that governs it. Source: Wikipedia (English translation of the Circuito RLC entry in Spanish).

2 Isabelle Stangers and Philippr Pignard: La brujería capitalista. Hekht, 2018. (English title: Capitalist Sorcery)

3 Martinez Estrada: Radiografía de la Pampa. Ediciones Losada, 2006. (English title: X-Ray of the Pampa)

4 Hal Foster: Belleza Compulsiva. Adriana Hidalgo, 2008. (English title: Compulsive Beauty)

5 VVAA: Redes de vanguardia. Amauta y América Latina. 1926-1930. Museo Reina Sofía, 2019. (English title: The Avant-Garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s)

6 Rafael Cippollini: “La verdad es que somos cualquier cosa”. Apuntes para una estrategia argentina del siglo XXI” in Prácticas contemporáneas, apuntes y aproximaciones. FNA, 2011.

7 Claudio Iglesias: Falsa Conciencia. Metales Pesados, 2017

8 Mark Fisher: Los fantasmas de mi vida. Caja Negra, 2018 (English title: The Ghosts of My Life)

ARTISTS

PATRICIO LARRAMBEBERE

EDUARDO MOLINARI